Opening Out

by Richard Silberg

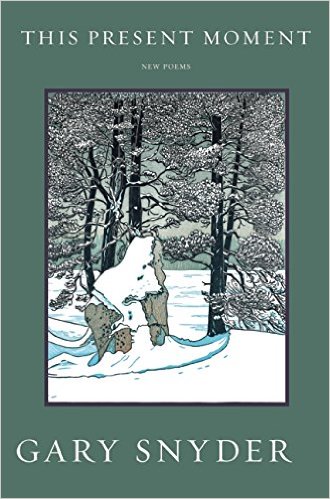

This Present Moment, by Gary Snyder, Counterpoint, Berkeley, 2015, 88 pages, $14.95 paperback. Nominated for the 2016 Northern California Book Award in Poetry.

Gary Snyder is often, maybe even usually, thought of as a Beat poet. That's a label he rejects. The faux-grouping is easy to understand. He was one of the five readers at the famous Six Gallery reading when Ginsberg debuted Howl. As 'Japhy Ryder' he's a key figure in Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums. But his work stands clear in its own unique, very unBeat space. I'd like to think about that a little as a way to ease us into a consideration of his new book of poems.

The Beats could be thought of as a species of Neoromanticism, a writing emphasizing the ego of the writer, a heightened emotionality—and let me add that I'm talking here entirely of poets that I love; these comparisons aren't invidious, they're descriptive. With the possible exception of Michael McClure, the major Beat writers are also largely urban in feel and setting.

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,

starving hysterical naked,dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking

for an angry fix,angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night…

These lines, probably the most quoted in twentieth-century poetry (my apologies), are, of course, Allen Ginsberg opening "Howl." The voice of the speaker is spotlighted, megaphoned; it's shamanic, agonistic. We're crawling the inner city. And everything about this poetry is heightened, strung towards a breaking point, the emotion, the language in its famous Whitmanic length and 'jazz' syncopations, the complication, adjectival and otherwise, of its description and imagery: "the starry dynamo in the machinery…"—another writer, 'tighter', might have gone with either "dynamo" or "machinery."

Gnashing everywhere in Consciousness

Throughout the ten directions of space

Occupying all the quarters in & out,

From supermicroscopic no-bug

To huge Galaxy Lightyear Bowell

Illuminating the sky of one Mind—

Poor! I wish I was free

of that slaving meat wheel

and safe in heaven dead

That's Jack Kerouac ending the 211th Chorus of "Mexico City Blues," riffing on the "wheel of the quivering meat conception." This is, of course, a very different voice from Ginsberg's. Ginsberg's voice in "Howl" has a public feel, pitched outward in a quasi-oratorical mode. Kerouac, on the other hand, is much more a voice of thought, Jack to the reader, or to the universe. But the quirkiness of his ego, his rich peculiarities as a 'languager' are front and center. The words are fast and 'bee-bop', both heightened, "supermicroscopic," "Galaxy Lightyear Bowell" with those capitals and the double 'l'; and offhand, childlike, "in & out," "no-bug," that expressive, shorthand, italicized, exclaimed "Poor!"

I have known Almighty Kindness Herself!

I have sat beside Her pure white feet,

gaining Her confidence!

We spoke of nothing unkind,

but one night I was tormented by those strange nurses,

those fat pontiffs

The little old lady rode a spiked car over my head!

The priest cut open my stomach, put his hands in me,

and cried: — Where's your soul? Where's your soul! —

The famous poet picked me up

and threw me out of the window!

Gregory Corso, brilliant bad boy of the Beats, from his "But I Do Not Need Kindness." The speaker here positively reeks of savage irony and humor, the priest, the poet, the little old lady in her fantastic spiked car. The language, in itself, is general, almost vanilla in its diction and abstractions, heightened only in its capitalizations and exclamation points. The subversion lies in tone and phrasing, in the underlying idea that sticks its tongue out at, scribbles across social pieties—although the poem in its entirety is actually deepened and lent ambiguity in its last section by something like loneliness, sadness, yearning.

Strikingly different as these three poets, and others of the essential Beats, are from each other, they share certain features that I'm trying to point up here, among which are a dramatizing, a foregrounding of the speaker, a powerful emotional charge, often shamanic or prophetic in tone, a heightening, what we could call expressive distortion, in discourse and depiction, an urban orientation, and let's throw in the rebellion, the social subversion for which the Beats were both notorious and celebrated.

Now let's look at a poem from the first section of This Present Moment. This is the ending of "Why I Take Good Care of My Macintosh," which is probably modeled after Christopher Smart's famous poem to his cat, Snyder propelling his poem with an extended anaphora of "because" phrases:

Because whole worlds of writing can be boldly laid out and then highlighted

and vanish in a flash at "delete,"

so it teaches of impermanence and pain;

And because my computer and me are both brief in this world,

both foolish, and we have earthly fates,

Because I have let it move in with me right in the tent,

And it goes with me out every morning;

We fill up our baskets, get back home,

Feel rich, relax,

I throw it a scrap and it hums.

The first thing that strikes me about this writing is its lightness and humor. It neither orates nor berates; rather it moves in affectionate play, although it grazes across "impermanence and pain" and other touches of 'samsara'. The language, itself, is transparent, easy, suited to its occasion. I actually can't think of an example in Snyder's work of language that foregrounds itself, that calls attention to itself as poetic, or mannered, that brandishes its brilliance. This modest, self-effacing speaker is decidedly unBeat, no shamanic thunder, no salvation cries, no social subversion. The setting, as we can tell from the "tent" and the filling up of baskets is solitary and rural—Snyder, of course, is our prototypical poet of the environment, of the 'wild'—and the poem is a delightful example of 'thisness', of clarity.

Now let's move from the immediacy of his Macintosh poem to a poem that takes a longer view. Here's "Anger, Cattle, and Achilles" in its entirety:

Two of my best friends quit speaking

one said his wrath was like that of Achilles.

The three of us had traveled on the desert,

awakened to bird song and sunshine under ironwoods

in a wadi south of the border.

They both were herders. One with cattle and poems,

the other with business and books.

One almost died in a car crash but slowly recovered

the other gave up all his friends,

took refuge in a city and studied the nuances of power.

One of them I haven't seen in years,

I met the other lately in the far back of a bar,

musicians playing near the window and he

sweetly told me "listen to that music.

The self we hold so dear will soon be gone."

Just to finish off our 'unBeat' discussion, listen to the evenness of Snyder's tone there. The speaker could be called a participant-informant, and the poem, which might be given to drama or schmaltz, or both—the very pairing of Snyder and schmaltz is an oxymoron—resorts to neither. Instead, the tone, which I think is deeply characteristic of him, is like a smooth bathing of light across the time and space of the story told, compassion and sadness deeply vibrant beneath. Let's also note the quiet wit of the poem, the "herder" idea to pair these feuding friends, and the suggestiveness of "nuances" in that phrase about power. The Buddhist letting go of ego and world, the poem's point and ending, speaks for itself.

Snyder is also given to the really long view as here, later in the book, in "Wildfire News," which begins, "For millions,// for hundreds of millions of years// there were fires.…" It ends like this:

Huge Sequoia

two foot thick fireproof bark fire pines, their cones love the heat,

how long to say,

that's how they covered the continents

ten lakhs of millennia or more.

I have to slow down my mind.

slow down my mind

Rome was built in a day.

Again there's fine wit, wit that powerfully signifies, in the last line. But perhaps more important is his expressed attempt to "slow down" his mind, what it tells us of a discipline of going beyond, of this man's attempt—really as all good poets do—but maybe especially this one—to slip personal confines, to perceive the larger.

Which, in a wide variety of ways, is what portions of This Present Moment are doing. Some of the poems seem to be more or less found poems, like "The Names of Actaeon's Hounds," which, exactly as the title says, is a vivid list of names which Snyder's notes tell us was taken from a translation of Ovid; "Old New Mexico Genetics," which is more or less a transcription of an eighteenth century listing of genetic possibilities he found on the wall of the Palace of Governors in Santa Fe; "Polyandry," which he says was taken from a book on the subject. Poems like this seem to me, again, to be an exercise in 'thisness', a kind of direct pouring of the world by way of Snyder's mindful selection through to the reader.

Something of this effect, although much more talked and thought, is produced by the opening of "Stories in the Night":

Yesterday I was working most of the day with a breakdown in the system.

Generator 1, Generator 2, old phased-out Generator 3,

the battery array, the big Trace inverter—solar panels—

they had all stopped—cold early morning in the dark—

back to the old days, kerosene lamp—candles—woodstoves always work—

the back up generator #3 Honda, cycles wrong? Tricking inverter relay that

starts the bulk charge?

But what starts out as a straight eavesdropping on Snyder's handy man or engineer's mind turns as the poem moves, a two-pager, into something very different. It cuts to 1962, a tour through Japan with his first wife, the poet Joanne Kyger, visiting Hiroshima, from there to thinking about the Bomb, about power, the Old Testament God, and much else. "Stories…" becomes a wide, intimate ramble across the poet's thinking, a ramble in the world as he thinks it, circling back towards the end to the generators, and finishing with this:

The old time people here in warm earth lodges thirty feet across

burned pitchy pinewood slivers for their candles,

snow after snow for all those centuries before—

lodgefire light and pitchy slivers burning—

don't need much light

for stories in the night.

This easy informality; 'This is where my thoughts are darting'; 'These are the poems, folks'—to paraphrase the old stand-up comedian's patter-line—seems to me very much another characteristic of his work. We should also note his warm reverencing of the "old time people" and for the candle-lit stories that give the poem its title.

Many poems here take us into more private niches of Snyder's experience, like the poem that takes us quietly into Hai-en Temple in South Korea (page 44), its chanting of sutras, its "great drum," bonging of bells, its eighty thousand carved birch wood blocks; like this poem, also, "The Earth's Wild Places":

Your eyes, your mouth and hands,

the public highways.

Hands, like truck stops,

semis rumbling in the corners.

Eyes like the bank clerk's window

foreign exchange.

I love all the parts of your body

friends hug your suburbs

farmlands are given a nod

but I know the path

to your wilderness.

It's not that I like it best,

but we're almost always

alone there,

and it's scary but also calm.

I want to come back to that essential image of the Earth as body of the lover later, but here it's that last line that takes me, that gives this city boy a special telephoto inkling of wilderness.

Here's another deep shot into wildness, the end of "Artemis and Pan":

Pan and Artemis

bow-twang or

open-sight .270 barks a puff

bring down a deer

and skin it together

eat fresh liver

cooked over embers

In the silvery light of the moon

How lovely that is and startling, even shocking. Artemis, chaste goddess of the hunt, and Pan, sexual, the satyr, who gave her the pick of his hunting hounds, the poem potently joins these two, as they've been joined in painting. Snyder gives the poem an epigraph from Thoreau, "The wildness of the savage is but a faint symbol of the awful ferity with which good men and lovers meet." In this penetrated deer, disemboweled, serving a savage appetite, "Artemis and Pan" images "ferity," wildness. Snyder seems to be recalling his own wild pleasures, in hunting—and in love as well? That last point is unclear to me. But the power is clear, delivered in the cut-back, abbreviated language, "bring down a deer…eat fresh liver," that he initiated, made characteristic in his celebrated 'bear shit in the trail' poems. And I wonder if he's secretly amused as well, knowing that most of his readers, me certainly included, if they've eaten venison at all, let alone deer liver, have only done so in high-toned restaurants.

There's much, much else in This Present Moment, "Starting the Spring Garden and Thinking of Thomas Jefferson," a meditation on gardening, time, democracy, slavery; "A Letter to M.A. Who Lives Far Away," a charming, rhymed letter to a young poet; "Charles Freer in a Sierra Snowstorm (little did I know)," a visit to a museum founded by a railroad tycoon to look at a Chinese scroll, probably, I'm guessing, to fertilize his work on his own epic poem Mountains and Rivers Without End.

But I want to close with a consideration of "Go Now," the book's penultimate poem, at four pages the longest in the book and given its own section. "Go Now" is an ultimate love poem, in several senses of the word. It's a poem on the death of his wife, last in that sense. But it's also a poem that goes as far as love can go, from life into death and beyond into death's corruption. It's complete and unwavering, delivered with Snyder's evenness, his factuality, a forthrightness that makes it truly searing.

In fact, Snyder knows, naturally, how painful it is—the inner eyes want to squint away—and he begins like this, in italics:

You don't want to read this,

reader,

be warned, turn back

from the darkness,

go now.

That last line contains the poem's title, but it clearly has a double meaning, warning the reader, as here, but in a larger sense he's speaking to his wife, bidding her farewell from this world. I'm not going to deal with the poem's climactic scene, a decision I've come to, actually, in the writing of this piece. I want prospective readers to come to the poem clean; I want you to take its full journey, taboo, power journey. I'll just set it up as he does:

…After ten long years.

So thin that the joints showed through,

each sinew and knob

Shakyamuni coming down from the mountain

after all that fasting

looked plumper than her.

"I met a walking

skeleton, his name was Thomas Quinn"— we sang

back then

she could barely walk, but she did.

I gave her the drugs every night and we always

kissed sweetly and fiercely after the push;

kissed hard, and our teeth clacked, her

lips dry, fierce, she was all

bones, breath and eyes.

On first reading "Go Now," it seemed to me isolate, a singularity in the book, which treats virtually not at all with love, with sickness, or with his wife until here. Then, thinking further, reading back through I found hints, the sense that This Present Moment makes a big circle. "The Earth's Wild Places," which we looked at just above, second poem in the book, imaging Earth as the body of a lover, seems in an inner meaning also to be a poem to her. "Go Now," towards its end says, "…her body,/ her body for sure, my sweet lady's body/ down to its essentials.…" Now here's the opening poem, which puzzled me somewhat when I first read it:

Gnarly

Splitting 18" long rounds from a beetle-kill

pine tree we felled

so it wouldn't smash a shed

—with a borrowed splitter briggs & stratton

twenty-ton pressure

wedge on a piston push-rod

some rounds fall clean down split in two,

some tough and thready, knotty,

full of frass and galleries, gnarly

gnarly!—my woman

she was sweet

So, a wide, mindful circle, which he closes on the page facing the last of "Go Now," black page printed in white, the title poem, shortest poem in the book:

This present moment

that lives on

to become

long ago

with its big, wide message. ![]()

Richard Silberg is the associate editor of Poetry Flash. His most recent books are The Horses: New & Selected Poems and Deconstruction of the Blues. He received the Northern California Book Award in Translation for his co-translation of Korean poet Ko Un's The Three Way Tavern. His most recent co-translations with Clare You are Ko Un's This Side of Time and I Must Be the Wind, poems by Moon Chung-Hee, from White Pine Press.

— posted July 2016

So Far So Good: Final Poems, 2014-2018

So Far So Good: Final Poems, 2014-2018  Abandoned Poems

Abandoned Poems

Mississippi

Mississippi