The Quantum of Kerouac

by Pat Nolan

"I know that I am just an imagery blossom."—Jean-Louis Kerouac

The Language of Jazz

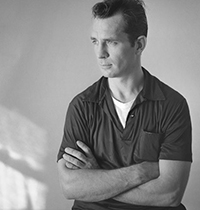

Jack Kerouac. I was seventeen when I came across the name, just getting my first taste of jazz listening to WJLB, an R&B station out of Inkster, Michigan. The late night DJ liked to throw in some Jimmy Smith Hammond organ jazz grooves. I was also boning up on jazz in Metronome, a music magazine, and one issue featured an article by Kerouac. The contributor's notes spoke of his sensational novel, On The Road, published a few years earlier. A novel about jazz I had to read. I was in for a big surprise. It wasn't about jazz in the way I thought it would be. But it was life changing, and the beginning of an education. Because of Jack Kerouac and On The Road, I picked up on Baudelaire and Rimbaud, the New American Poetry, the San Francisco scene, spontaneous bop prosody, and most of all, the pantheon of jazz greats, the gods of bebop. Jack Kerouac was their prophet.

My curiosity about jazz led me to Kerouac, and over the years that association has remained. I've tried to understand jazz as Kerouac had, as music and as a language. As music, its basis is polyrhythmic and percussive. And as a language, it speaks in metered polytonal phrases. Layered rhythms and counter rhythms add a redundancy and nuance to what is being said. Kenneth Rexroth's comment, that Kerouac knew nothing about jazz or Negroes, notwithstanding, Jack Kerouac understood both the music and the language, intuitively grasping the essential idiom of bop, readily receptive to the underlying message of liberation. He heard it say, "The world belongs to me because I am poor." And he was keen for the spoken word associated with jazz and its performers, the secret and joyful lexicon of hep cats as epitomized by that style-setting paragon of cool, Lester Young, and in Lord Buckley's jazzy scat-like monologues. On The Road illustrates that there can be music in the telling of a story and in the rhythmic digressions of improvisation.

Getting On The Road

Gilbert Milstein's 1957 New York Times review still stands as one of the most perceptive and prescient assessments of On The Road. Significant, perhaps, is that Milstein was also a music critic, specifically jazz. The review opens unequivocally claiming the novel as an "historic occasion in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment in an age in which the attention is fragmented and the sensibilities are blunted by the superlatives of fashion (multiplied a millionfold by the speed and pound of communications)." Adding "On the Road is the most beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance…by turns, awesome, tender and funny…that has never been equaled in American fiction, either for insight, style or technical virtuosity," Milstein proclaimed On the Road "a major novel."

Milstein also predicted the opposition On The Road would face when he writes "it will be condescended to by, or make uneasy, the neo-academicians and the 'official' avant-garde critics, and that it will be dealt with superficially elsewhere as merely 'absorbing' or 'intriguing' or 'picaresque' or any of a dozen convenient banalities, not excluding 'off beat.'" He could not have anticipated the tidal wave of vitriol directed at the novel or the public disparagement of its author. To the white Anglo Saxon Protestant ethos prevalent among the entrenched literati and salon mavens of the Atlantic shore, Canuck Kerouac represented a threat to the shaky partisan edifice they had constructed. The unsanctioned (and unwashed) anti-intellectual autodidacts of Beatdom gave them Bolshevik nightmares.

Even to this day I am continually taken aback by the vehemence with which Kerouac is denounced and the bland, senseless dismissals his writing still encounters. Kerouac confounds those in the thrall of the idea that there is such a thing as proper English. He, in fact, writes in the vernacular, Americain, Americano, or as Lew Welch called it, Murican. In its rollicking headlong slapstick peregrinations, On The Road resembles the vaudevillian human comedy of Gogol's Dead Souls. Similarly, it is also the work of troubled genius.

A Perfect Storm

A perfect storm of Kerouac related activity over the last year drew me back into the orbit of my main literary progenitor. First there was talk that On The Road was being made into a major motion picture. Around that time I also read Gerald Nicosia's One And Only, The True Story Behind On The Road. Perhaps not so coincidentally, Gerald Nicosia was a consultant on the movie production and provided Kristen Stewart, the star attraction, with tape recordings of his interview with Lu Anne Henderson to help her get into the role of Marylou. And not least, I also read, with much pleasure and anticipation, Joyce Johnson's new biography The Voice Is All, The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac which places a significant emphasis on Kerouac's French Canadian background.

Personally, I have always doubted that a Hollywood adaptation of On The Road could be successful. On The Road is too vast a work to be captured within the constraints of a conventional production. And the literary aspects of On The Road, the attributes that make it a great and unique work of literature, are next to impossible to translate into a viable cinematic expression. Perhaps Eisenstein might have managed a mind-bending montage approximation of Buster Keaton pratfalls and near misses that would have left the viewers dizzy and exhausted. Terrence Malick could have made a go at it, capturing the range, the breadth, the pace with panoramic filmscapes and judicious lyrical voiceovers in a little over three hours. Nonetheless, there would still be gaps, stretches that are not visually accessible. The question is, can a mere two hours do justice to On The Road and be anything more than a road trip buddy flick given gravitas through association with the great novel of the Beat generation? Popular young actor Kristen Stewart of Twilight vampire movie fame, cast as Marylou, Dean Moriarty's child bride, will undoubtedly be the focus of this feature. In the novel she plays a critical though ancillary role. Funny how Hollywood thinks group sex and mutual masturbation are the bases of great literature. But not to judge too harshly a movie I haven't seen and don't intend to see, perhaps some young readers drawn to the star power of their favorite young actor will pick up a copy of On The Road and have their lives transformed by the novel as was mine.

One and Only

In One And Only; The Untold Story of On The Road & Lu Anne Henderson, The Woman Who Started Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady On Their Journey authored by Gerald Nicosia and Anne Marie Santos, Marylou can be found as her real life counterpart, Lu Anne Henderson. As depicted in the novel, Marylou is sexually promiscuous and sexual partner to both Dean Moriarty and Sal Paradise. Kerouac scholar and biographer Nicosia states in the introduction to One And Only that Lu Anne Henderson is the one who brought the two men together, helping them overcome their juvenile competitiveness and forging the bond that drives the novel. Lu Anne's words give a depth and humanity to the relationship between the real life Dean Moriarty and Sal Paradise, and Marylou.

At the core of One And Only is the transcription of seven hours of Lu Anne Henderson's recollections of her relationship with Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac taped in 1978 by Nicosia who was then fashioning his definitive Kerouac biography, Memory Babe. Nicosia provides an introduction for this oral history, detailing the circumstances of the interview and the reason why it has remained under wraps until now. And he brackets the interview with a critical afterword, drawing on his extensive knowledge of the life and work of Jack Kerouac.

To his credit, Nicosia allows Lu Anne Henderson to speak for herself, and her voice is palpable. That Neal was Lu Anne's first love is evident from her testimony, as it is in that of Lu Anne's daughter, Anne Marie Santos, and Ed Hinkle's addendums rounding out this slim volume. The bond of affection, both physical and emotional, between Lu Anne and Neal continued long after they separated and Neal had married Carolyn, the mother of his children. The authenticity and immediacy of Lu Anne's voice in the transcription highlights a self-effacement that downplays her role in what is arguably the great picaresque novel of the twentieth century. What comes through is an unflinching account of Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac as young men, their dreams and aspirations, their strengths and their faults.

Reading the transcription of the taped interview, recorded twelve years after Kerouac's death, the impression is of someone sympathetic and warm, recounting in an unaffected way her relationship with Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady. Young Jack is recalled as goofy, serious, and trying too hard to joyfully participate in the sorrows of the world while emulating the great saints and writers of history of whom he and Neal talked endlessly. These weren't university kids. They were autodidacts, outlaws, seekers, pilgrims in search of a grail, the flash of enlightenment that would give meaning to the mundane. Kerouac's novels are all about the mundane, the pitiless circumstances of daily existence as the source of human sorrow, and why we should go "moan for man."

Kerouac apologized to his friends, Lu Anne relates, for portraying them so nakedly in On The Road, and for what he felt was a betrayal of their trust. They forgave him, but it is likely that he continued to harbor that guilt, especially after the notoriety began to pile up, and he saw how it affected his friendships. And it was to change everything. As Jack wrote to Allen Ginsberg, "Fame makes you stop writing."

For me, this is where the needle skips the groove. There are two Kerouacs, a pre media-burn Jack, and a fried to a crisp post-On The Road Kerouac. These two recent books, by Nicosia and Johnson, center on early Jack. Lu Anne's story relates an eyewitness account of much of the autobiographical basis for the novel. Joyce Johnson chooses to halt her biographical narrative in 1951.

Full Disclosure

I was struck by the truth of both the title and subhead of Joyce Johnson's biography, The Voice Is All, The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac. The title speaks to the ethnic root of Kerouac's language, and the lonely victory, at this remove, quite evident in the public self-destruction under the continued media assault surrounding his person and his writing.

In the interest of full disclosure, I must admit to a bias: I am also French Canadian. Don't let the name fool you. I was born in Montreal. French is my first language and the one I spoke exclusively up until I was ten (outside of compulsory English schooling where to even speak the language of my birth was a disciplinary offense). Then my family moved to the States; I got my green card, and the opportunities to speak Quebecois were severely limited.

My early years as a French speaker were in many ways similar to those of Kerouac's. I guess that makes me bilingual. Jack Kerouac was as well, though not many people think of him as a bilingual author, as a writer who got his start in a language other than the Anglo coin of the realm.

It's been my experience that the original language, while no longer functioning as the primary lexical source, will often make its influence known, sometimes in subversive ways. An idea can begin in French only to end up expressed in English. Or vice versa. As a code-switching youngster, I spoke the language that best expressed what I wanted to say. Word choices are often affected or are archaic in usage. I personally have a tendency toward reflexive verbs and prepositional phrases. Adjectival modifiers often get misplaced. I doubt that any of this is at all unusual to anyone who has more than one language as their experience. French, like Swedish, Chinese and some African languages, is nuanced in tone. This lends itself to ambiguity and the bane of proper English, puns. Jazz can be that way, in the punning improvisations of solos. So too is Jack's prose, whose playfulness owes much to the language of his birth, and to bebop.

To my Canuck ear the most glaringly obvious example of word play in On The Road is the name of the novel's protagonist, Sal Paradise. 'Sal' is a diminutive of 'salaud' which denotes a slob, someone who needs to take a shower. Sal Paradise is 'Dirty' Paradise, the unwashed working class hero. That's Jack's in-joke, and in perfect keeping with the clannish conventions of self-deprecation, of not making yourself out to be better than anyone else, a polite humility common to rural French Canadians.

The cultural environment Johnson describes in The Voice Is All resonates as being close to what I remember growing up in a French Canadian household. As late as the fifties Quebec was slow in joining the twentieth century. Horse drawn plows were a common sight in farm fields worked by descendants of Breton peasants whose brand of Catholicism had hardly changed since the seventeenth century. It was lean and mean with no thought to Vatican II appeasements. The indoctrination was rigorous and thorough. Every youngster aspired to a halo.

Another aspect of French Canadian family life of that time is the ubiquity of original radio soap operas or radioromans, unique in expressing Quebecker morality and ethos in a language that owed much to its early peasant influence. We tend to forget what an anciently deep and primitive source that tradition draws on, one that up until recently was only marginally affected by the modern world. Kerouac was heir to that tradition, including the child terrifying hair-raising tales of loup garou, or les sauvages whose blood also trickled through their veins, and perhaps above all, the fabled characters of one of the longest running soap operas broadcast on CBF, the French Canadian radio network. "Un homme et son péché/A Man and His Sin," was a highly moral saga continually confronting the treachery, greed and jealousy of the most sinful of men, Seraphin. It was entertainment with a worldview deeply steeped in a primal religious austerity redeemed through the salvation of hope. Families gathered around the kitchen tables listening to radio tales of the cold cruel world in a language and idiom unique to their culture.

The Voice Is All

Joyce Johnson recreates, in her 2012 biography, Kerouac's emergence as a writer from the shaping world of his adolescence to the self-torture of his impulsive genius that put him always on the precipice of failure while alternately making him wildly optimistic and messianic. She outlines the underpinnings of what will eventually find its way into On The Road. There is a realization that the vivacity with which Kerouac is charging his writing is the balladeering, myth-making praise songs of self-made heroics and legends of him and his pals. It attains the grandeur of a spiritual quest because that is Kerouac's turn of mind. He is the altar boy heretical failed priest shaman beckoning "follow me, men, I know the way!" in the great vision quest novel of the twentieth century.

Although some of the material in The Voice Is All has been addressed in other biographies and memoirs, Johnson brings a visceral presence, a personal insight not available to the cross section of scholars who can only rely on secondhand accounts. Her story, benefiting from a strong sense of narrative, hangs together without having to solely depend on the iterations of quote and citation, and makes reading about Kerouac's early development as a writer compelling. For Johnson, it's personal, and the reader is readily admitted to that sense of intimacy. By ending her biography in Kerouac's thirtieth year, Johnson brings the reader to the brink of an incredible period of creativity that encompasses the next dozen years and rightfully deserves a volume of its own. She has a rough row to hoe, however, what with the petrified quibbles of clueless Brit reviewers on the one hand, and on the other, the sharpened knives of academic hacks protecting their miserable little slices of Kerouac turf with their internecine squabbles.

Johnson does confirm the native ancestry in Kerouac's family, on his mother's side, in their Iroquois blood. Though this marker is often cited as proof of greater authenticity in a nation of immigrants, among the early settlers to New France, marriage alliances with native families were not uncommon. The devastation of alcoholism among native populations is borne out in full lurid display in the last years of Jack's life. Again, that last chapter of Kerouac's life undoubtedly deserves its own volume as well.

Ending the narrative at that early date, Johnson preserves a picture of Kerouac as innocent, in many respects intransigently naïve, bumming about on a Rimbaudian soul-deranging mission of quasi-holy man, reaching for that epiphany, and maintaining in his writing the voice he heard in his head, a voice that shaped his writing, voice of another language, because as he well knew, language is culture, and the voice is all.

The Quantum

If you bother to look, there is much on Kerouac in print, on disk, on the Internet. Certainly more than I am ultimately interested in. On the other hand, I have read everything of Kerouac's that has been put in print. I have also read, or attempted to read, all the biographies, memoirs, and ancillary tie-ins. I read David Amram's delightful memoir, Offbeat, and the accounts of rent parties with the main attraction being Amram on French horn and Kerouac improvising poems, monologues like a six story walk-up shaman. What is lost to history! Also in these pages is a vivid recounting of the recording session for the voice-over narration by Jack of Robert Frank's Pull My Daisy. Perhaps an even ghostlier glimpse comes from unedited film footage available on YouTube, shot by Frank outside a bar in the Village. There a darkly handsome, self-assured, perhaps slightly pugnacious or drunk, or both, man with a lot of French body language swaggers through in black and white like Zelig. This is Jack on the cusp.

Critical study and commentary on Kerouac's writing to my reckoning is overshadowed by and lags behind the biographical material. The primarily biographical focus on Kerouac reflects the fact no one can properly deal with the writing outside of that context. And he hasn't made it easy by hewing so close to autobiography in enacting the morality play of his messianism. With a few exceptions, the memoirs and quasi-biographies center on the author and treat the novels as thinly disguised autobiography. Kerouac's writing seems almost beside the point and trivial compared to the iconic nature of the man himself, King of The Beats, emblem of a generation, etc.

A plainspoken assessment of On The Road is presented in John Leland's Why Kerouac Matters. It lays out a schematic of talking points. While sometimes a little stuffy, Leland's very smart book, which could have easily been titled 'Kerouac for Dummies,' outlines the salient aspects of the novel to make them read like life lessons aimed at a new generation of readers. What is missing in this deconstruction is the complexity of Jack's voice.

Philip Whalen, someone Kerouac had great respect for, and equal in American mystic tendencies, speaking of Kerouac, said he thought of himself as an experimental writer. A Kerouac confidant, Whalen interviewed by Larry Lee and Barry Gifford in Off The Wall, a collection of Whalen interviews, provides the expected no-nonsense view of his old friend. Speaking of the novels, Whalen said, "They were not reportage. Those things were created. They were made. They were composed in a very particular way. They are very well written, beautifully composed and put together. The idea that he simply sat down at a typewriter, that he wasn't a writer, he was a typist, that isn't so." Of Kerouac himself, Whalen says, "He was very interesting because he also saw so much, he was always so aware of his own experience and what he was seeing, what he was hearing, what he remembered."

A 1964 capsule critique by Gilbert Sorrentino (The Floating Bear 30) offers a backhanded compliment, claiming that it appeared that Kerouac had bypassed the precision mitered examples offered by Flaubert, Conrad and Maddox Ford for something akin to earlier eighteenth century prose fiction. It seems like an outrageous claim because Kerouac's first novel, The Town And The Country, owed much to Thomas Wolff. On the other hand, eighteenth century prose had yet to rid itself of the vestiges of orality. The voice was still all-important. Kerouac realized, as had Whitman, another unique American voice vilified, that the self is the fountainhead of creativity, touchstone of great spirituality.

Professor Eric Havelock writes in The Muse Learns To Write that the reemergence of orality in the twentieth century is due in part to the radio. Over the airwaves, along with propaganda, quiz and variety shows, fireside chats, and soap operas, came musical performances, including dance music, in particular jazz, risen from a culture of vibrant orality. That sense of the spoken is on full display in Visions Of Cody. As Clark Coolidge so perceptively notes in Now It's Jazz, Writings On Kerouac & The Sounds, "This is a wide open Kerouac voice book. All his moves in single continuant length. Best, it gets read all out in a sitting…from here to there, this to that, a graph of all mind syncline/ anticline swept on a line. Run the whole form through your head. & you miss him if you don't hear him. Nodes of mind moving in voice moving mind. Great range of thought overtones, harmonics. The voice box of Jack Kerouac."

A particularly visceral Kerouac document came about when Ted Berrigan and his merry troupe of New York poets descended on Jack to interview him for The Paris Review, and install him in the pantheon of great American writers with their attention. To them he was the mystical brujo, old Father Bhikkhu Blues, Holy Jack, Saint Jack grooving to the vast sorrows of existence with his dark native look and primitive sense of fatality. We choose our gods from among those who are most like us.

Jack's soulfulness was his fatal flaw. His spiritual side sought the uplifting of epiphany, ecstatic transport. It's something French Canadian kids learn at a young age, the transcendent experience expressed in sadomasochistic iconography. Twelve years from the publication of On The Road to his death, Kerouac had completed twelve of the fourteen stations of his agony and death. The thirteenth and fourteenth stations? Enacted by his followers who take him down from the criminal's place and lay him to rest with the honor and reverence he deserves. Jack was crucified by misunderstanding, sensationalism, crass ignorance and the envy of the Ivy League clan. His was a slow death. Witness the progress to virtual suicide in Paul Maher's Empty Phantoms. It is one of the saddest documents, this testimony of self-destruction. And even though the outcome is inevitable, the end still comes as a shock. As Jack would say, "Writing solves nothing."

Or view the succession of videos and images of Jack suffering from severe media burn now available with ubiquity on the Internet or as documentaries. Watching them tries your empathy and is bound to ruin your day. Among the field of documentaries—and I probably have watched them all—the Lewis MacAdams product, What Happened to Kerouac?, is probably the least cringe-worthy. Almost all the documentaries feature clips of Jack on Firing Line, a parody of himself, of the successful novelist, blaming the younger generation for misunderstanding him. He is the picture of the classic French Canadian uncle—he could have easily been one of mine—and like so many hard working Canucks, lithe and intense in their youth, beery and blowsy in their dotage. And just a little crazy. Ti Jean was a peasant, an urban country boy, whose bad habits and body followed a natural downward spiral into alcoholic depression as he obliterated himself in a messy working class orgy of self-destruction.

On The Road ultimately is about Sal Paradise, his epiphanies, the real, the imagined, the literal, and the literary. A continuum of music underlies it all. It is a dream of freedom much as Jazz, bebop in particular, is the voice of freedom. His novels are achingly autobiographical, but they are not about him as much as they are the singing of the saga of self with a galloping enthusiasm and uncompromising innocence in romantic praiseful cadences. The exuberance of hyperbole belongs to the young, the idealist. Then someone comes along and paints a bull's eye on you.

Wind Blown Dream

On occasion I've wondered what would have happened if the review of On The Road had been ignored. What if someone had said, "ah, that Milstein he's a hack, don't pay any attention to him." Realistically, Milstein's review was not the only match to light the fuse to Kerouac's rocket. There were so many other factors, not the least of them, the belief in Kerouac's genius by his friends. It is that genius that deserves appreciation and respect.

For some, the touting of Kerouac as a great writer was a wound that would not scab. One critic in particular made his reputation in New York literary circles by attacking and demonizing Kerouac and his associates. The hysterical denouncements caught the attention of the media dogs, always ready to chase the scent of sensationalism.

In reading Nicosia's One And Only, I was drawn back into the fold of On The Road, not having read it in many, many years. It was at once familiar and strange, dreamlike in that many things were familiar but not in that context. And as much as the adventures of Sal and Dean are compelling in their own boisterous way, this time around it was the episode with Terry (Bea Franco) that was the sweetest, most touching.

Johnson's The Voice Is All put me back in touch with the unique culture of my childhood, and reminded me of the affiliation, in the root sense of the word, the sense of kinship, I felt with Kerouac. That it's taken me fifty years to articulate it is another matter for another time.

Some years ago I came upon Windblown World, a selection of Kerouac's journals and working notes from the late forties, early fifties. The title resonated with me because it reminded me of a line by Basho. No appreciation of Kerouac would be complete without mentioning his enthusiasm for haiku and his appropriation of the Japanese verse form as American Haiku, much to the chagrin of haiku purists. For Kerouac, it was the pared down essence of seeing, at which he was so adept, as a moment of transformative experience expressed in the cadences of haiku in translation, particularly those of R.H. Blyth. Of course those who don't care for haiku probably number among those who don't care for Kerouac's novels.

Along with the sketches, development notes, plot idea, word counts and pep talks in Windblown World, a young Kerouac lists his aspirations, his hopes, his dreams. He aspired to become a successful novelist and have the leisure to read all the great works of world literature, and of course write to his heart's content. In one passage, his dream is to move to Northern California with a wife and raise a family. That gave me pause. Other than the part about being a successful novelist, I was essentially living Kerouac's dream. Then it occurred to me: I can't be the only one. Somewhere, down along the cove, the next ridge over, up the coast, off the beaten track there must be others who are sharing that dream.

In this collective dream, I can listen to the lords of bebop recorded live at Massey Hall or the rediscovered re-appreciated Volume Two with Davis, Johnson, and the Heath brothers, and think of Jack. I stand at my window any given morning, cup in hand, and watch wisps of mist snagged on the fir and redwood ridge across the river, and think of Jack. Or on the way back from an afternoon walk, a bank of ocean fog encroaching on the burnished orange gold of the saw-tooth skyline, I think of Jack. Yes, I think of Jack Kerouac. ![]()

Pat Nolan lives along the lower Russian River in northern California. His latest novel is The Last Resort, from Nualláin House, Publishers, 2012, nuallainhousepublishers.com.

Photo by Tom Palumbo, circa 1956.

— posted June 2013