What of the What?

by Dean Rader

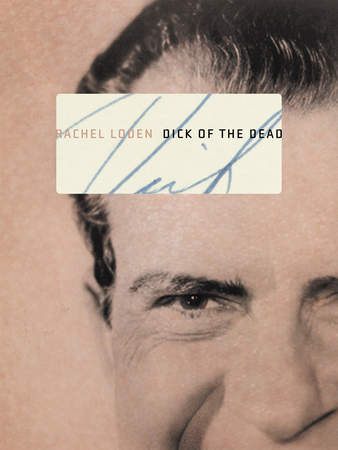

Dick of the Dead, by Rachel Loden. Ahsahta Press, Boise, Idaho, 2009, 102 pages, paperback $17.50.

When I saw Rachel Loden's new book of poems, my first reaction was, well, I guess that title's taken.

Okay, so maybe Dick of the Dead was not on my shortlist for potential book titles, but it should have been. Iambic and monosyllabic, alliterative and polysemic, it's both a little funny, and a little dirty. It's a great title for a great book, in part because it's conducive but also more than a tad elusive

A perfect storm of Dickness leads the reader to believe that the book will take Richard "Tricky Dick" Nixon head on, so to speak. First, there is Loden's previous book, Hotel Imperium, (2008), which digs its poetic scalpel into the cadaver of the Nixon White House. Second, the design of this new collection foregrounds the former president with a gigantic close-up of Nixon on the front cover, and a bizarre but pleasing "Separated at Birth" style photo pairing on the back in which Nixon and Loden appear side-by-side. And, third there is that title: Dick of the Dead. I mean, come on! With such a headline, how could you not assume the centrality of Tricky Dick?

But, Loden proves to be just as tricky. Of the fifty-eight poems in the book, only eleven deal directly with Nixon. In fact, the most famous (or infamous) poems in Dick of the Dead are two pieces that flirt with lesbianism—a project that may or may not have interested America's thirty-seventh Commander-in-Chief. So, an obvious question emerges—why the title? And why make Nixon appear to be at the core of the book when over three-fourths of the book is about other topics?

The answer to that question is yet another of Loden's tricks. Yes, Nixon functions as a biographical figure and a kind of foil, but Nixon's Nixonness—what he stands for—becomes a controlling metaphor for the entire book. It extends way beyond those eleven poems that mention him directly. If we think of Nixon as an embodiment of power corrupted, as a manifestation of empire both fatuous and flaccid, as a symbol of ambitions at the expense of ethics, then the quilt of Loden's book (with Nixon as its raveling and unraveling thread) unfolds in provocative ways. Think of it: Nixon as both subject and object. Nixon as metaphor and metonym. Nixon as Dick, Cheney as Dick, W. as Dick, John Wayne as Dick, Hugh Hefner as Dick, and even Donald Rumsfeld as Dick, as in the book's title poem:

Sent out the crows to the four corners, did I?

Cheney's heart is skipping for me.

Swept sandstorm with the dead ones, did I?

Rumsfeld's spectral legions know me.

Prayed on the White House floor with Henry?

Dr. Rice is kneeling for me.

Unfurled, we see that big quilt now. It's a mosaic of madness and malfeasance. Nixon is every politician, and every politician is Nixon. For Loden, Washington is a bit like one of those Whack-A-Mole games—as soon as you smash one rodent, another pops up.

And, here is where things get really interesting. There turns out to be a whole book of moles!

In Loden's world, Nixon functions not only as a metaphor for political corruption but for a multitude of petty tyrants and minions of empire. For example, Loden casts Hugh Hefner, Valerie Solanas, Vladimir Putin, and J. Edgar Hoover in major cameo roles in Dick of the Dead. However, we know they are only actors. Or, more accurately, they are creations. We know we are supposed to read them not as themselves but as dark inventions forged in the black fire of Nixon's workshop. This means of course that Nixon is everywhere: in the movies, in porn, in Russia, in the FBI. He is the most paradoxical of paradoxes. He is even where he isn't; even though he's dead, he is still very much alive.

In yet another paradox, it is Loden who keeps Dick's shriveled heart beating, and it is worth asking what her connection to him actually is. In a poem like "The Bride of Frankenstein" Loden makes the monstrous connection (and her complicity?) implicit. Is Nixon Frankenstein or the monster? But, in the stunning and disturbing "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Station," that unholy marriage is more explicit:

…It could happen. Mayhap

after a last smile from Evelina, who slowly wheels her heavy

many-dialed machine away. The heart murmurs, talking

a very little to itself. I am Aschenputtel, it says, also known

as Drella, known as Tattercoats, known as Cinder Thing.

Do not cross me. For often I am permitted to lie spread-

eagled on a scroll of paper, reading a colorful magazine.

Here, Loden plays with the self's ability to inhabit many forms, to take on multiple identities, to be the bodiless body every Nixon wants. The poem turns the body into the desired but discarded thing that is the afflatus of empire. The used-up, the spent and splayed. Given the fact that the opening poem in the collection is entitled "Miss October" and figures the speaker (Loden?) as the "…girl / Of drifting leaves, cold cheeks // And passionate regrets" who tempts the Viagra-popping Hef, it is not a stretch to assume the magazine at the end of one poem is the very magazine that comprises the setting for the opening poem. The poet, square in the viewfinder, is naked, exposed, subjugated. And yet, not. Either way, dick, here, takes on a whole other meaning.

The same might be said for "station." In one of stranger mashups in the book, Loden takes the classic poem by Ezra Pound (the Nixon of American poetry?) and gives it a good jolt. Formed in that black fire, that dark workshop, Loden takes Pound's corpse,

In a Station of the Metro

The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

Petals on a wet, black bough .

and zaps it with some tazers, some drones, some crazy laser beams and resuscitates it as:

The USNS Comfort Sails to the Gulf

Huge red crosses on the whitewashed hull:

http://www.comfort.navy.mil/welcome.html.

I don't even know how to write about this poem. It defies explication, but Loden's interest in stations, as a place one returns to over and over again, suggests that one's destination is really not about arrival but unpacking.

A brief note on Loden and explication. Because her 'themes' are so bizarre and the topics of her poems so unconventional, critics and reviewers never talk about Loden's poetic style, her use of language, or her sense of craft. I would argue that Dick of the Dead is as successful as it is mostly because Loden is a consummate craftsperson. Like Emily Dickinson, Loden's poems are frightfully compact. Most of the poems are less than a page in length. She has squeezed all explication into the sink and wrung the poems dry. Everything in the poem is essential and strong, so it can carry the heavy rucksack of multiple meanings, references, and allusions.

But the poems can also be beautiful, like Miss October herself. Lush and luxuriant if also a bit campy:

My heart tick-tocking like Captain Hook's clock.

Does Tricky wait for any godforsaken crocodile,

idling and glimmering in the nearby calms?

Bah. But now if I'd been Blackbeard's boatswain

(as I should have been) Pan and the lost boys

would have long since walked the plank.

So no going gentle, I think, into that gute Nacht

as birdshot Harry knows in his pocked hide.

Let the press laugh. I dressed my mutt

Jackson in Lord Vader's duds

just to show I get the joke. Bad luck like a fever

that will not break in Mesopotamia and here

(from "Cheney Agonistes")

Just note, if you will, that smart internal rhyme (tocking and clock) in the opening line that gets replayed again (crocodile) a few words later. Notice also the subtle rhyme of the last syllable of crocodile and idling that comes just after the line break. Because the poem is funny, the reader may miss the magnificent merging of B's in line four (Bah. But now if I'd been Blackbeard's boatswain), the hard guttural echoes of Nacht and mutt, the lovely assonance of "So no going" and "to show I get the joke" and that great couplet of "fever" and "here." Even if you catch those, you might not catch the steady iambs that keep the poem's clock tick-tocking. The entire book is full of such poetic moments, and I'd encourage the reader, after going through once trying to figure everything out, to return for a second or third reading to take in that music.

Dick of the Dead is weird book. But, this is a weird world. Ultimately, it's a brave book because it isn't afraid to make deep connections and devilish associations across generations, genres, and genders. Loden reminds us that it's not really the lunatics who are running the asylum—it's us. ![]()

Dean Rader is the author of Works & Days, winner of the 2010 T.S. Eliot Poetry Prize. He is professor of English at the University of San Francisco, and regularly contributes op-eds and book reviews to San Francisco Chronicle and blogs at The Weekly Rader, SemiObama, and 52 Gavins.