Between Tildes ~ Writing as Mosaic ~

by Jesse Morse

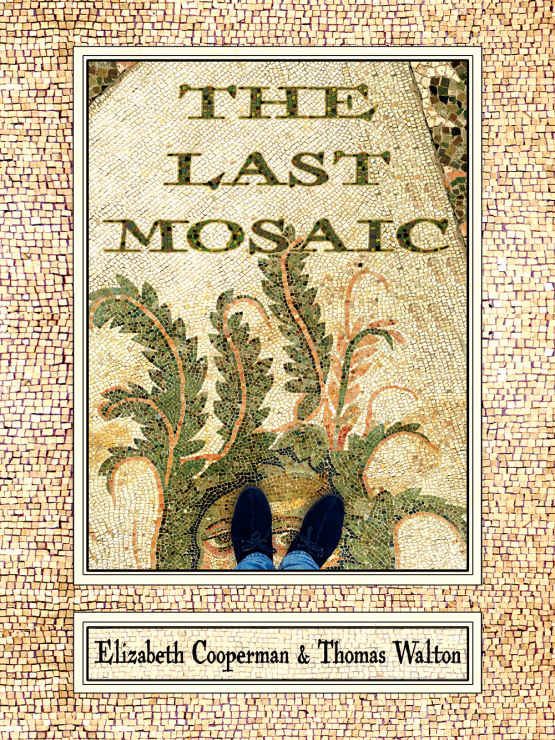

The Last Mosaic, by Elizabeth Cooperman and Thomas Walton, Sagging Shorts series, Sagging Meniscus Press, Montclair, New Jersey, 2018, 138 pages, $12.99 paperback, www.SaggingMeniscus.com.

EARLY ON IN The Last Mosaic, the narrator proclaims "Writing imitates other media that express things better." Directly following the proclamation is an invitation to "feel free to cut these out and arrange them pictorially however you like." The "these" the narrator refers to are the vignettes/fragments/sentences/quotes that comprise the entirety of The Last Mosaic. Separated by tildes and grouped loosely into chapters, the book does call to mind a Burroughs-like cut-up, yet The Last Mosaic reads, thankfully, from vignette to vignette, more cohesively than literary experiments from sixty years ago. Even if the reader is invited to cut-up the parts of The Last Mosaic and rearrange them pictorially to help "express things better," one suspects the co-authors have already taken up this challenge themselves. Indeed, turning to the "References" in the back of the book, one finds that this idea, that writing imitates other, more efficacious media, "bubbled up in conversation with Richard Kenney; and [is] taken here as a challenge." While the book's modus operandi is to bring up a great many ideas and observations quickly and then let them go, the brief exposition in these two lines, and the self-acknowledged challenge later on, seem like good advice to follow for anyone navigating the pages of The Last Mosaic.

Co-authors Elizabeth Cooperman and Thomas Walton set their book in Rome, both contemporary and historical Rome, and the book reads part-journal, part-travelogue, part-quote catalogue, part-historical reference text, part-adventure, part-conversation, part-search for beauty and truth. Though we find fragment upon fragment upon fragment in a great many contemporary books attempting to blur the lines of memoir, essay and lyric essay (think Sarah Manguso's 300 Arguments—Manguso is quoted in The Last Mosaic more than once, in fact), the book does not contain enough of a narrative or expository thread to categorize it as lyric essay, nor is there enough personal detail to set it firmly in memoir. In his review in The Seattle Review of Books, Paul Constant refers to The Last Mosaic as a journal, and then reminds his readers that "journals are messy," though journals generally imply an audience of one—the author—and the authors in this case surely weren't writing only to themselves, despite parts of it reading as journalistic. So how do we categorize this book?

If titles remain an indication of projects as a whole, then we can think of The Last Mosaic as exactly that, a mosaic (even more so when considering the authors' challenge at the outset: that writing can "express" just as well as other media). Throughout The Last Mosaic, the authors sojourn to many of Rome's mosaics, they spend time elucidating what actually comprises a mosaic, they touch on the history of mosaics, and discuss why and when mosaics fell out of fashion. These mini-pilgrimages to the various mosaics of Rome serve as impetus for the book as a whole, and the corresponding structure and ensuing aesthetic can be thought of as trying to embody the mosaic in written form:

~

The mosaics in the Villa Giulia employ such small pieces of fractured tile that they almost seem to be oil paintings…almost. If you stand back twenty feet or more, they are oil paintings. As you step closer, the cracked assemblage reveals itself. Fish lurch, Gorgons tremble, a squid twitches.

~

(page 6)

Information is fleeting throughout The Last Mosaic, and this further bolsters the notion that the moments between tildes act as tesserae—individual tiles, working together to comprise the whole. Only by stepping back can you see the mosaic (poem) in its proper form. Furthermore, one can correlate the sense of (a crumbling) permanence of an ancient mosaic on a wall or floor to this book in hand, flipped through again and again, entered at various places, eventually placed on a table, landing in a bookshelf, pulled out again and perused by a future reader. To appreciate a mosaic you don't necessarily need to understand what lay behind it, or exactly when it was made or how it was constructed; the looking is enough.

~

Tessera is derived from Greek, meaning "four." To tessellate is to form into a mosaic pattern.

I might say Rome but what I mean is more.

~

(page 11)

This calling to and embodying of mosaics is perhaps best exemplified in the authors' choice to never distinguish who, in fact, is speaking or writing. Conflating the narrator and author(s) is a reader's natural tendency, but the beauty of this choice by the authors lies in forcing the reader to do away with that tendency; forcing the reader to take the text on its own terms, and consciously sever the desire to ascribe this moment to Cooperman or that moment to Walton. While Constant claims "a little bit more conversation between the authors might have added to the investigatory feel of the book" this would have belied its mosaic form. One wonders, in fact, how Cooperman and Walton comprised the book. Were the moments between tildes written individually, and then put together, almost as a call and response? Were the authors prone to edit each other? Or, even further, did the authors write into each other's lines? Do the authors even know, at this point, who wrote what? While surely the authors could answer these questions, the excitement lies in The Last Mosaic's ability to, in fact, come off as mosaic while existing as written word. A third voice emerges: that of the mosaic.

While searching after a new written form is clearly what excites this reviewer the most about The Last Mosaic, it would be negligent to dismiss the book as only that. Though, as mentioned before, expository threads in The Last Mosaic are fleeting at best, and a narrative thread is non-existent, we do, wading through the book, get a sense of what this third voice of The Last Mosaic is most interested in: beauty. Beauty is found in Rome's sculptures, mosaics, history, cafes, parks, flowers, and sounds, among other things. The book reads as an homage, in a sense, to beauty, and celebrates beauty's role, historically, as the central sought after aesthetic of the works of art that bubble up in The Last Mosaic:

~

Bernini was said to have achieved, through chiaroscuro effects, a sense of color flickering in stone.

~

(page 57)

Of course, the works that are mentioned also have a connection to Rome, in that they can generally be found there, and any author that is quoted or talked about either wrote about Rome or spent time there. Keats's spirit resonates throughout The Last Mosaic (Keats is buried in Rome), and Lawrence's Etruscan Places and Dante's Inferno play central roles. Myriad mosaic artists, painters, and sculptors are discussed. However, this third voice of The Last Mosaic is not deceived: much of this approbation of beauty turns to consternation at the lack of beauty in modern life; even going as far as to say modern concerns have made Keats seem misguided:

~

Keats says "Beauty obliterates all other consideration." Have you considered walking across the city in one-hundred-degree heat, having eaten nothing but a cornetto simplice, six shots of espresso vermiculating in your stomach?

I'm sorry, but I'd rather eat that Caravaggio than look at it.

~

(page 76)

Moreover, The Last Mosaic thinks back to times when beauty was vacated as the driving force behind artistic impulse:

~

Christian works were not meant to represent harmony and beauty, as Greco-Roman sculpture did. On the contrary, the emaciated bodies and faces had to express despair and suffering in order to impress on the laity Christ's sacrifice and passion.

Art became didactic; culture declined.

~

(page 70)

This oscillating of beauty's role in art, and questing after what beauty is actually seen and available to the artist adrift in the world, drives the bricolage-like structure of The Last Mosaic more than any other concern. Yet as the book carries on, immersed in the paintings, sculptures, and natural observations that define the allure of Rome, one feels that beauty loses. Rome's murderous history, for instance, is inextricable from the landscape. The grating noise of the city's recycling trucks at 5 a.m. cannot be ignored. Essentially, the beauty the authors seek, and are perhaps hoping to create themselves, proves elusive. The world gets in the way. Nevertheless, the authors recognize this and nod their collective head to it: the limits of their project, which, of course, shouldn't make one shy away from it:

~

I say Italy but this is what I mean: all that I can hold and then put here. A fraction really, of a song. A truncate vision of an illimitable thing. Still, it is Italy and I am in it. The sun fills the valley below and I sit high above it, in the shade of the hill, some oaks, on the terrace, cool and pleasant now but soon to be unbearably hot, the day already nearly ruined.

(page 81)

While The Last Mosaic is largely successful in what it sets out to accomplish (a mosaic form; a tireless searching), one wonders—if a written mosaic is in fact what the authors were after—why this should be the last one? The form offers a freedom that other writers could find useful, and it has worked especially well in this case for a book that was co-authored. Indeed, the third voice that emerges in this book feels as if someone or something nascent rose from the intimate nature of the writing relationship that undoubtedly took place in the writing of this work (tenfold, given Cooperman and Walton's long-standing romantic relationship). Of course, "last" can also mean "most recent," and perhaps that is what the authors were after, but, in either case, one wonders if The Rome Mosaic would have been a more a propos title, given the city's front and center role throughout the entire book (despite an occasional venture outside the city limits).

The only other consternation I found myself grappling with was what, in fact, is entirely integral to the compilation of the mosaic/poem as a whole. The strength of The Last Mosaic lies in its continual observational quality, its indefatigable searching after mosaic, sculpture, and beauty, and this is generally enough. It's just that some parts of this search resonate more than others, and without the overarching whole to subsume those parts into a larger end (as you'd do in a novel), one finds oneself wondering how this or that moment fits in. Nevertheless, this question wanes as one grows accustomed to the book, and it is likewise balanced by the varying tone The Last Mosaic employs. The authors do not shy away from the occasional exclamation point, for instance, in the hope of comedic effect! Cumulatively, the book demands we do away with our traditional reading expectations; a natural byproduct of which can be to try to shape the book to our own needs and ends, rather than allowing the book to be what it is. It is from this urge to shape, one suspects, that these suspicions emerge, and it is why, as one grows more familiar with the mosaic/poem, these suspicions fade away.

In the end, The Last Mosaic can be read in any direction and opened anywhere, much like viewing a mosaic (even if the authors enter Rome in the opening pages and leave it near the end). The perspective shifts throughout the text, and one imagines the unknown and unimaginable insights that are revealed in a close-up examination of one tessera, contrasted with viewing a mosaic only from afar. The successful co-authorship is refreshing, and it's important to note that a book like this (no narrative, no extended exposition) can find a home. Walton has another book scheduled for publication this June (The World Is All That Does Befall Us, from Ravenna Press), dubbed an "anti-lyric-essay lyric essay" in his author bio at the back of The Last Mosaic. The impetus is intriguing, given what a catch phrase "lyric essay" has become. Clearly Cooperman and Walton's hope is to continue to write against the grain. ![]()

Jesse Morse lives in Portland, Oregon and adjuncts at Clark College in Vancouver, Washington. He has a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Denver and publishes poetry and book reviews in a variety of places including Oregon Sports News, where he is a regular columnist. He also helps curate 1122 Gallery with his wife, poet Jennifer Denrow, and artist Lauren Schaefer, out of his garage, and plays guitar and sings in the rock band The Whirlies.

— posted May 2019