To Be a Poet

by Lucille Lang Day

THE FIRST TIME I HEARD about the Berkeley Poets Co-op was when my friend Paul Aebersold showed me a set of colorful posters he'd made by silk-screening his photographs and pairing them with quotes from poems by Co-op members. It was the fall of 1971, and I was twenty-three years old.

Although I was a graduate student in Zoology, the idea of the Co-op intrigued me because I had aspired to be a poet since childhood. I began to think of myself as a poet after writing my first poem at age six. It went like this:

Down in the hollow

of the old oak tree

in the hills of paradise,

there the little birdies sing

and swing in the trees above,

down in the hollow

of the old oak tree

in the hills of paradise.

I was trying to capture the point of view of an old person nostalgically remembering childhood. In my first draft I said "old nut tree," but I changed it to "old oak tree" because I liked the repetition of the "o" sounds. I didn't know the word "assonance," but I thought I was onto something. When I showed the poem to my first grade teacher, Miss Clydesdale, however, I was sorry, because she asked me to read it to the class. Too shy to do so, I looked down and mumbled. It would be another twenty years before I could enjoy giving a poetry reading.

In fifth grade my desire to be a poet intensified when I encountered Emily Dickinson's poem "Success." I was enthralled by "To comprehend a nectar / requires sorest need." Anticipating adulthood, I knew I would not always get what I wanted (I already didn't!), and this was a fabulous way of expressing that. I wanted to write like that too, but I knew that my own poems were only those of a child. I was eager to grow up and write real poems, and I did not think I would need any special study or training to do it. I thought it would just happen when I grew up.

At fourteen, in love with love poetry and love itself, I memorized poems from a little book called Love Letters & Love Poems for All the Year, which I'd bought at H.C. Capwell's department store in downtown Oakland: "The Passionate Shepherd to His Love," "How Do I Love Thee?," "A Red, Red Rose," "We'll Go No More A-Roving," and "Love's Philosophy." Eager to marry my sixteen-year-old boyfriend, I felt like the following verses from "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time," by Robert Herrick, had been written especially for me:

That age is best, which is the first,

When youth and blood are warmer But being spent, the worse, and worst

Times still succeed the former. Then be not coy, but use your time,

And while ye may, go marry: For having lost but once your prime,

You may forever tarry.

It did not occur to me that I might not have reached my prime yet.

Throughout my teen years, I wrote many poems, hoping that eventually my efforts would produce the real poems I longed to write, and that I'd know when that happened. Even though I was a teen mother and high school dropout, it was clear to me that not all verse was real poetry. I knew, for example, that greeting card verses were not in the same category with the poems I loved by Dickinson, Marlow, Barrett Browning, Burns, Byron, Shelley, and Herrick. No one had taught me what constituted a real poem, but I intuited that it must be original in some way—in its ideas, images, or turns of language.

One poem of my own that I was pleased with at first was about the irony of riding a Harley at sixteen with a boy I'd met at a church dance at thirteen. My mother said she didn't like the part about the motorcycle. As far as I was concerned, if there was no motorcycle, there was no poem. I thought it must be a bad poem, so I threw it away. I didn't understand that my mother wouldn't like any poem with a motorcycle in it.

As an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, where I had the good fortune to be accepted after being out of school between the ages of fourteen and seventeen, I decided to major in science although I still wanted to be a poet. I now wanted to be both a scientist and a writer, and no one told me these were both full-time jobs. Emily Dickinson and Madame Curie were my heroines. I thought that by studying science I could maximize my contribution to society, increase my employability, and have another whole realm of knowledge to bring to my writing.

I didn't find much time to write during my college years, but in the spring of my senior year, 1971, my muse woke up. I wrote a lot of poems and submitted some to contests for Berkeley students. As a biology major who'd taken three literature classes, I knew I was at a disadvantage, but I hoped nevertheless that I might win something.

I received Honorable Mention for a group of seven rhymed poems I submitted to the Dorothy Rosenberg Memorial Prize competition in Lyric Poetry. The congratulatory letter I received from the chair of the prize committee said that Professor Harder, who had judged the contest, wrote, "The author of manuscript 208 should be given Honorable Mention for his/her sensitive treatment of several topical themes. I am sorry there is no second prize." I came in second against the undergraduate and graduate English majors! I took this as a sign that I was a true poet. I now realize that the poems I sent to the Dorothy Rosenberg contest were juvenilia, but at the time I didn't even know what juvenilia was.

* * *

MY FRIEND PAUL decided to sell the communal house he owned and ran in Oakland. His real estate agent, Kathleen Raven, was a member of the Berkeley Poets Co-op, and she and Paul held a party on April 1, 1972, to celebrate the sale of the house. It was my opportunity to meet the Co-op members.

As I leaned against a doorpost and tapped my foot in time to the music, Ted Fleischman, one of the Co-op cofounders, said, "You look like you want to dance."

We danced; we dated; we shared our poetry, and by summer we were living together. All spring and summer I pleaded with Ted to take me to a Berkeley Poets Co-op meeting, but he said they already had enough people and advised me to start my own group. I would later learn that Co-op meetings were open to anyone who wanted to attend. I think he didn't want to take me because he didn't think my poems were very good and didn't think the other Co-op members would, either. Finally, in August, he said they didn't have so many people now and it was a good time to join.

The Co-op was then meeting in the living room of Charles and Maggie Entrekin's house on Oregon Street in Berkeley. At my first workshop, I decided to read a couple of my Honorable Mention poems, although I considered them finished poems, because I thought they were my best poems and I wanted to make a good impression. When I looked up at the faces around me as I read the opening lines of "I Hear Them" ("I hear them / As they make the fields ring. / At six. a.m. / Outside my pane they sing"), I knew I was in trouble. There were a few moments of stunned silence after I finished. Then the dozen or so poets present informed me that the poem was trite, boring, and predictable. I read another poem and received the same response.

Thinking maybe these weren't the best of my best poems, I went back the following week and read a couple more of my Honorable Mention poems, including one dedicated to Heisenberg and written from the point of view of an electron. It begins: "Is the magic probability/Four pi psi-quared, r-squared dee r? / Do you really think you'll catch me / Near the atom's crackling star?" This time, the Co-op members lost their patience with me. One man summed up the feeling in the room as he said with exasperation: "We told you last week to stop writing this stuff!"

This did not deter me from going back. I thought the Co-op members disliked my poems because they were rhymed, and I took it as a challenge to write a good unrhymed poem, something that they would praise. To get inspired, I started reading several books of contemporary poetry every week (so much for my graduate work in zoology!). Up until then, my favorite poets had been Keats, Shelley, Dickinson, and Millay. Now I discovered that I liked Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and William Carlos Williams just as well.

Every Wednesday night I took my latest efforts to the Co-op workshop. I was not completely satisfied with this work myself, so I was neither surprised nor offended when it was criticized. What really surprised me was that I found it hard to write unrhymed poetry that was any good. I knew my rhymed poems were not in the same league as those of Shelley or Keats, but I could excuse myself for not attaining the highest level in something that at least looked difficult. It was harder to excuse myself for not excelling at something that, to me at least, looked easy.

After I'd been attending the Co-op meetings for a few months, two other poets who wrote formal poems as well as free verse came on the scene: Marcia Falk and Dan Balderston. To my astonishment, Marcia's poem "A Letter to the Sons of Abraham," written in rhyming quatrains in iambic pentameter, and Dan's sonnet "To Emily Dickinson" practically received standing ovations. So the Co-op members weren't totally opposed to rhymed poems! I asked Charles Entrekin why people liked Marcia's and Dan's rhymed poems but not mine. He said, "Because theirs use contemporary language and deal with contemporary issues."

I enjoyed presenting my poems at the Co-op, hearing poems by other poets, hearing critiques of the other poems, and also responding to poems myself. I discovered that even as one of the least experienced members of a literary workshop, I could always find something to say. This was in sharp contrast to my behavior in science seminars, where I was often as mute as the chairs, feeling more like an observer than a participant in the goings on. I began to realize that I was more a writer than a scientist, and that in a literary milieu my greatest inspiration and strongest opinions would surface.

Alas, however, writing a good poem was no easy matter, despite the excellent feedback I received at the workshops from many poets—including Alicia Suskin Ostriker, who came to the Co-op while on sabbatical from Rutgers—and it was about a year before I could write a halfway decent poem with any reliability. It felt like a breakthrough in July 1973 when I wrote a poem called "The Lab," which was about feeling alienated and inadequate in the laboratory. It begins, "My snails caress / the planetary stillness, / dropping opaque eggs / to settle among the elements," and proceeds to such observations as, "The green oscilloscope snakes / hiss at me, and I shrivel." My shortcomings as a scientist had led to my writing something that I thought might be a real poem at last.

I attended the Co-op workshop pretty regularly for four years, but in 1976, I decided I wanted feedback on my work from a wider range of writers. That summer I went to the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, and in the fall I applied to take Josephine Miles's poetry class at UC Berkeley. It was a combination literature course and workshop, and to get in, one had to submit a packet of poems. I was apprehensive applying, having no relevant academic background (I'd completed my MA in Zoology at Berkeley and was now pursuing my PhD in Science/Mathematics Education), but she accepted me.

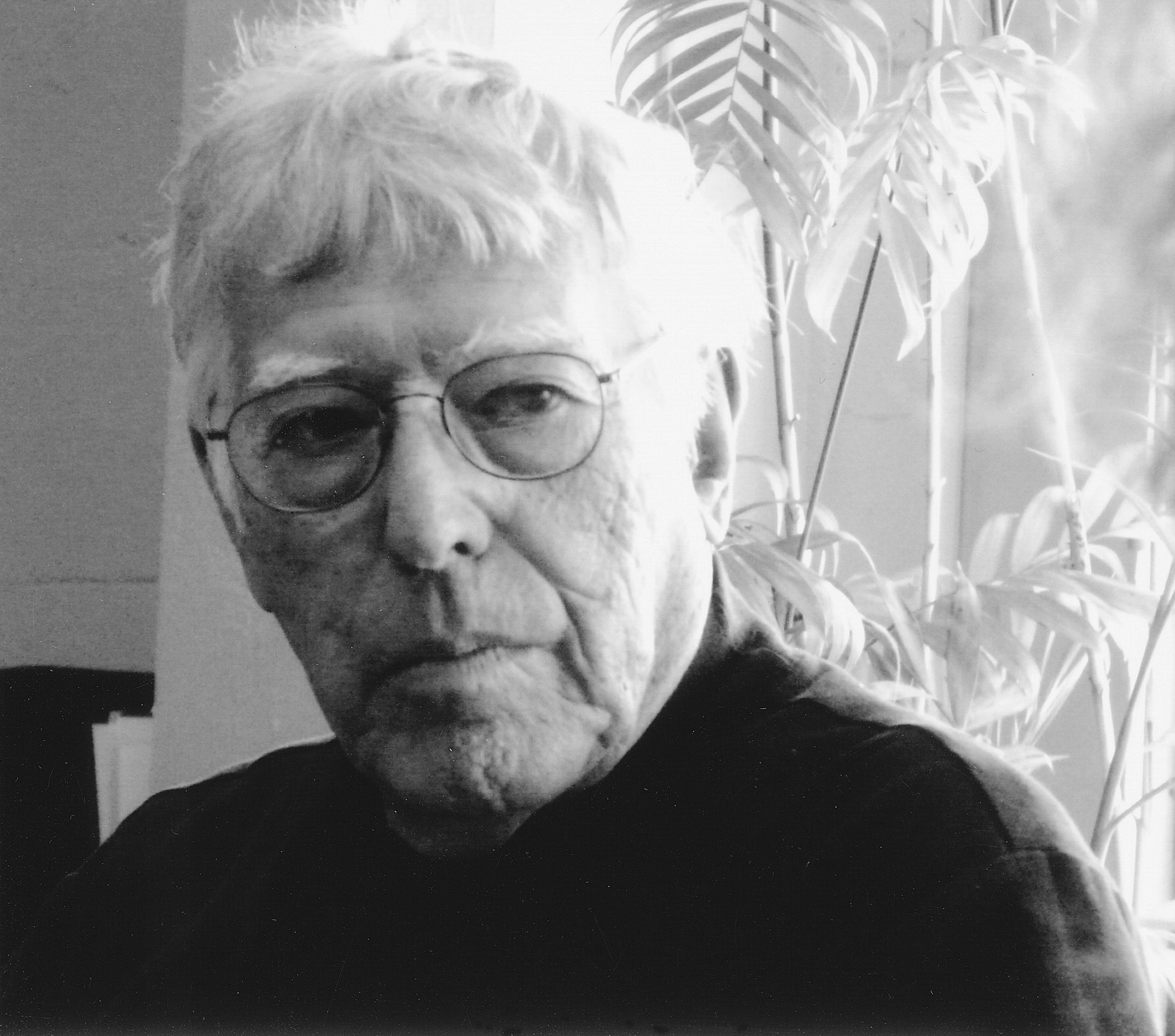

A fragile-looking woman in her sixties, Miles had a warm smile. She leaned against the wall outside the doorway of her classroom in Wheeler Hall to greet the students as they arrived. With slow, careful steps, she walked, stooped but unassisted, to her chair at the front of the room. Her fingers, knotted and twisted, had very little flexibility as she turned the pages of her notes. I hadn't known until then that she'd had severe rheumatoid arthritis since childhood. She was the first female English professor at Berkeley and also my own first female professor in any subject. I understood immediately that overcoming any disadvantage she'd encountered by being a woman had been the easy part.

But it was her words that mattered. She talked about all kinds of poetry that quarter—odes and chants, sonnets and ballads, confessional poetry and the poetry of rock. She explained how poems worked so that we could understand why a Shakespearean sonnet or a thirteenth century haiku moved us. We could draw on the traditions of many peoples and periods in our own work, she said, but advised us, first and foremost, to "write twentieth century American poetry. Capture your own time."

One of the poems I wrote that quarter was "First Wedding," about my very early venture into matrimony:

FIRST WEDDING

If the sky that day had opened not its blue room,

but its gray one, and we had been wed

rain-drenched in Reno, thunder cracking,

it wouldn't have mattered. But the sun was out

to brighten the walls of the old stone church.

All the dolls were long dead by then,

cold and waxy in their cribs and shoe box beds

on closet shelves, dust collecting like memories.

I was fourteen, wearing new white shoes

and my blue-flowered satin Chinese dress.

Mark was three years older, looking skinny

in his rented suit. Our mothers asked the organist

to play "I Love You Truly," and they crooned

and wept. I pretended it was "Love Me Tender."

The men were silent. My father bowed his head.

Standing at the altar, I remembered my blue room.

For years the walls had been shrinking.

I saw myself grown huge like Alice

in a box, small and blue, the door shrunken

to shoe box size. I had to burn my way out.

Now, in the cool light of the sanctuary

all my wounds were soothed. Mark was smiling.

It was hard not to giggle, saying "I do,"

and when we knelt I thought my dress would rip,

but it held, and my hand grew heavy with diamonds.

Afterward we went outside for pictures

to put in our white-and-gold vinyl book.

We stood under leaves, before a wall of stone,

and now I stare at the girl in the blue Chinese dress.

O child behind my mirror, smiling, trapped.

(from Self-Portrait with Hand Microscope, 1982)

Miles advised me to change "whiten" to "brighten" in the fifth line. She also suggested that I change the last line, which was originally the unbelievably awful "Sometimes, I think she's my mother and she's dead." Good advice!

An optimist, Miles told us that students were getting better and better, even though SAT scores were declining nationwide. "Scores are declining because more people are finishing high school and taking the SAT," she said. "People are really better-educated and more literate than ever. The average achievement level is rising, and the top students are better than ever too. I know this firsthand: my poetry students this year are the best I've ever had!" She stopped to smile and survey the room, taking in the smiles of the students as we basked in her praise. My classmates included novelist Mona Simpson and screenwriter Terry Borst, so there was indeed some budding talent in the room.

She praised us individually and as a group. She told me that students like me made teaching worthwhile. "You've broken the sound barrier," she said. I should have replied, "It's teachers like you who make being a student worthwhile."

After each class she rose and walked slowly back to the doorway. One afternoon I lingered to talk with her as she leaned again against the wall outside the classroom. After all of the students had left except me, an attendant waiting across the hallway came and picked her up in his arms like a child. Laws requiring the accessibility of buildings were still rudimentary. As the attendant held her, she said, "Don't feel sorry for me. Some people feel sorry for me when they see me like this, but they shouldn't. It's not a bad thing to be carried around by handsome young men." She grinned, adding, "Not a bad thing at all," as they headed toward the van waiting outside.

* * *

MY NEXT STOP on the road to becoming a poet was the graduate Creative Writing Program at San Francisco State University, where I enrolled in a workshop with Kathleen Fraser in the spring of 1978.

Fraser was an animated young woman with long auburn hair and a gap between her front teeth. Her hands moved incessantly as she talked about poetry. At the first class meeting, she asked us to introduce ourselves and say something about our poetry. I said that science, art, love, and motherhood had all played important roles in mine. At the next class a young man read a poem that to my ear sounded like a parody of what I had said, but he claimed that he was trying to honor me. I will never know for sure!

Fraser's assignments led me into new territory. One assignment was to write a poem in sections linked by association rather than linear, narrative logic. I liked doing this so well that I immediately wrote several such poems instead of just one. The one that I chose to present to the class was called "Inside the Pine Cones." It included the lines "The plane was hijacked / to Las Vegas. The terrorists / played keno all afternoon," and it concluded "the Rhine maiden / says Kaddish."

A young man with a broad, flushed face said. "You've degraded the terrorists. Terrorists would never play keno."

"The last line doesn't work at all," added a prematurely balding man who offered his critical commentary on everything that was read. "It's overstated. The Rhine maiden wouldn't know Kaddish."

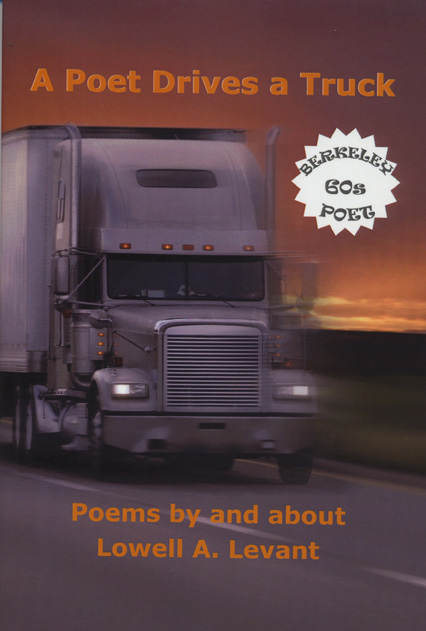

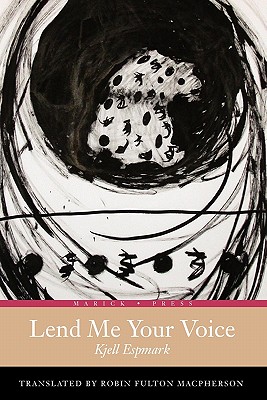

Fraser explained satire and irony to my classmates. In addition to the poets I studied with, novelist Herbert Gold, whom I'd met at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, encouraged me. "When I read your poems, then ones by famous poets," he said, "I can't tell that theirs are any better. You should be submitting to the best magazines." This advice inspired me to submit to The Hudson Review and The Threepenny Review, where my work was accepted, and to Poetry and The Paris Review, where it was rejected. Oh, well! Gold also insisted that I keep applying for the Joseph Henry Jackson Award even after I'd been rejected four times, and in 1982, the fifth time I applied, my first poetry collection, Self-Portrait with Hand Microscope, was selected for the award by Robert Pinsky, David Littlejohn, and Michael Rubin. Berkeley Poets' Workshop and Press published the book later that year.

Although I have used my degrees in Zoology and Science/Mathematics Education to earn my living through the years as a science writer and educator, I eventually also earned an MA in English and MFA in Creative Writing at San Francisco State. In addition to Kathleen Fraser, the poets I studied with there included Stan Rice, Daniel J. Langton, Toni Mirosovich, Stacy Doris, and Meg Schoerke. I learned from all of them, including Doris, an experimental poet whose work was as different from mine as the sky is from a tree. For Doris, I did things like cutting up five newspaper articles and constructing a poem out of the fragments. To sonneteers out there who can't see the point in this, all I can say is to try it. You might be surprised!

For my chapbook The Book of Answers, I am indebted to Pablo Neruda's The Book of Questions and also to Doris, under whose tutelage my brain got wired in many new ways through both her writing assignments and her reading assignments, which included things I never otherwise would have looked at, like the essays "Rhizome" and "Postulates of Linguistics" by the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. Here is a poem from The Book of Answers:

AMONG HUMPBACK WHALES,

WHERE DOES A PROTEST SONG LEAD?

It will pass unnoticed

under the waves

in the great heave and suck

of the sea, and the whales

will go on singing

for months on end,

weaving low, resonant

notes for mating or pleasure

until they reach Baja, where

in backyards and dumps

turtle shells pile up,

swearing at you and me.

(from The Book of Answers, 2006)

Ultimately, I came to realize that it isn't your teachers, your prizes, or your publications that make you a poet. It's the ability to get excited by lines like "the listener, who listens in the snow, / And, nothing himself, beholds / Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is" (Wallace Stevens, "The Snow Man"), to be jealous of someone who could write "never met this fellow, / Attended or alone, / Without a tighter breathing, / And zero at the bone" (Emily Dickinson, "A narrow fellow in the grass"), and to notice that "The pears fatten like little buddhas. / A blue mist is dragging the lake." (Sylvia Plath, "The Manor Garden"). Also, I think that being a poet consists much more in working on the forty drafts than in receiving your contributor's copy of the magazine containing the finished poem.

Having studied the Moderns, the Postmoderns, the Imagists, the Symbolists, the Objectivists, the Projectivists, the Beats, the Confessionals, and the Language poets, I have been won over by the virtues of free verse, and these days, that's what I'm mostly inspired to write. Nevertheless, occasionally a sonnet or villanelle will arrive at the door to my brain and demand to be let in, which connects me not only to the New Formalists but also to the Romantics and some of my earliest poetic roots. T.S. Eliot's quote from the "Four Quartets," which has been cited in many contexts, is relevant here: "We shall not cease from exploration/ And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time." Thus, I can now write a sonnet, not as a naïve twenty-two year old, but as someone who knows both why many people became bored with this type of poem and why many others are now trying to make it new:

WATCHING THE GREBES

Clear Lake, California

A taut blue sky is stretched above the lake,

which glitters like a rippling field of stars

in early sun. Two Western grebes take

a morning swim, but they don't go far

before they plunge. When they emerge, beaks

filled with weeds, they stand. It's time to dance!

Long necks held high, black crests and white cheeks

side by side, they glide as though on skis, advance

toward us. Standing on the balcony,

we see the shining wake they leave behind.

My love, I'd like to be as easy

as the grebes, who seem content to find

a dancing partner as the new day starts—

a dark-winged bird that knows the steps by heart.

(from Birds of San Pancho and Other Poems of Place, 2020)

Lucille Lang Day has published six full-length poetry collections and four chapbooks. Her seventh collection, Birds of San Pancho and Other Poems of Place was just published by Blue Light Press. She has co-edited two anthologies, Red Indian Road West: Native American Poetry from California and Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California, and is the author of two children's books, Chain Letter and The Rainbow Zoo. She also published a memoir, Married at Fourteen: A True Story, that received a PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award, and was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award in Creative Nonfiction.

— posted DECEMBER 2020