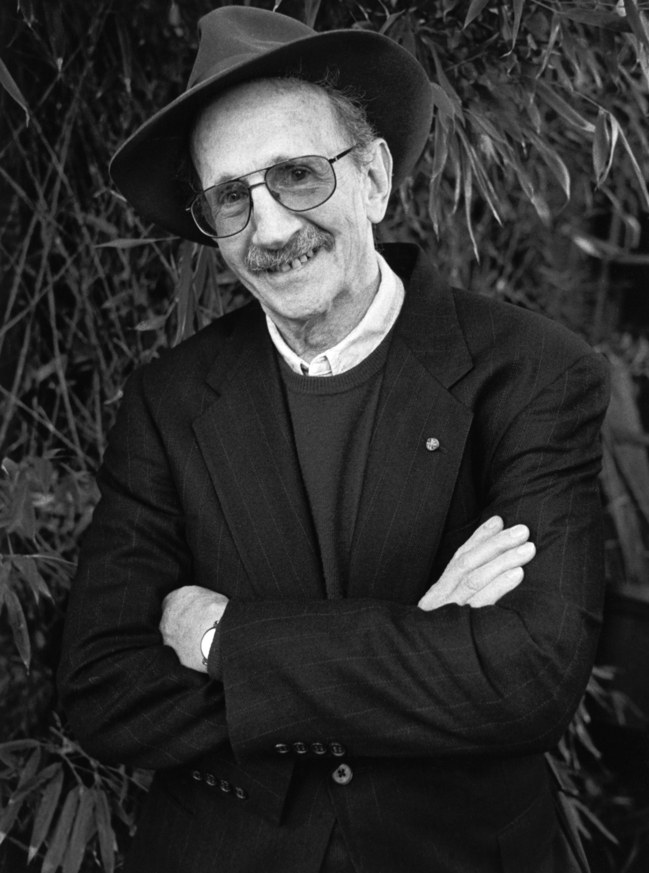

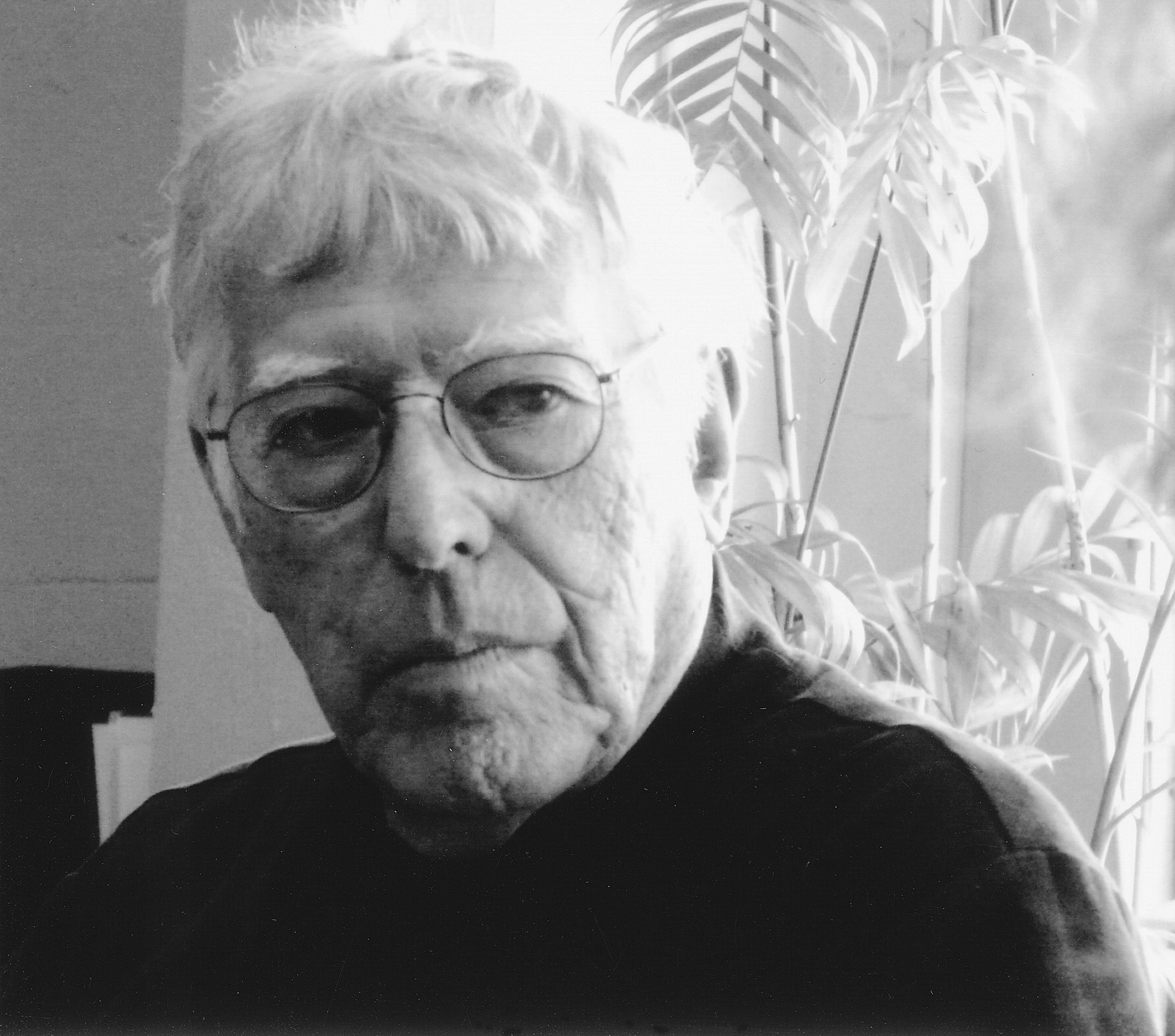

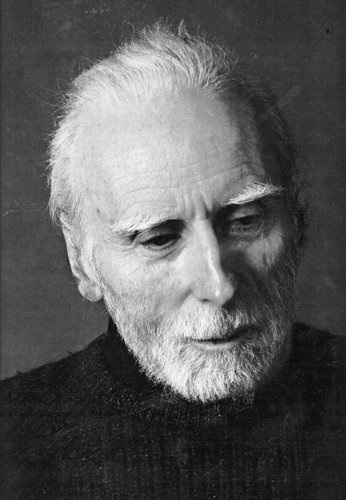

Postscript for Julia Vinograd

by Richard Loranger

JULIA'S GONE AND it feels like the end of an era. I didn't expect that; I knew she would pass soon and it didn't occur to me once, but it really, deeply does feel that way. Julia was the core of something, a beating heart that moved a lot of psyches forward through momentum of poetry. Those psyches will continue to move forward, 'cause that's what psyches do, but they'll have to get used to a different torque, a slightly different engine propelling them. Because Julia Vinograd was a poetry engine—that's what she did, and that's all she did. She lived her life for poetry, a rare commodity in the human strain and one less and less likely to recur in this breakneck era. But she did, and did so in an extraordinary manner, through sheer force of necessity. Because let's face it, it's not as if she had a choice.

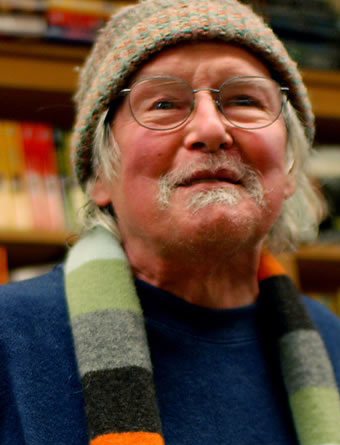

For Julia, poetry came first, second, and always, at least it seemed to. She lived with a disability most of her life, leg twisted from childhood polio, which translates as more than seven decades of pain, discomfort, and challenges that were definitely present in her life, sometimes more apparently present than others, especially when she walked, more and more slowly as the years went on. (When she passed, I burned a snail-shaped candle for her on my altar.) But at most times, it was easy to forget her disability, because she didn't let it define her—she let her poetry do that. She wrote constantly, at least from her twenties onward, got by on little in a room that filled slowly for decades with artwork and power objects and baubles, and lived to write and read her work. I summon her seventy-one [some say seventy] books as testament to that. She lived in and through her work, creating a world of her seeing. In a way her work is a testament to seeing, to the act and enactment of seeing. She strove to present the world she saw with utmost honesty, unshrouded by presumption or conceit. Often wry, and honest always. Ask anyone whose work she didn't care for or think was up to par, because she would tell ya. Her work was plainspoken and vivid, much like herself, but not naive, especially when it came to human nature or spirit. Whether her poems were narrative or fantastical, and she had plenty of both, sometimes blended, they were all, at core, poems of observation, and her reader easily intuits they can trust that she says what she sees, clearly and concisely. She said early on that she'd hang out on the streets of Berkeley and wait for a poem to walk by. Sometimes it seems to me that many of her poems had been hanging out for eons waiting for Julia Vinograd to happen by.

There was a uniqueness to how Julia lived and what she did. Are there other poets as prolific? Yes. Are there others as driven? Yes. Are there others whose lives are as entwined with their work, with its meaning, its purpose, its production? That's where things get less yessy. There are many writers who produce prolifically because they want to or need to, but Julia seemed to take that a step further—she seemed to live to produce, and her life exemplified the spirit of her work, the soul of the streets and of human striving, mystical, angry, sly, petulant, in the moment. I don't mean to exalt or pedestalize her here—as a person she was quite human, full of foibles—stubborn, sharp-tongued, self-focused, impractical—but all in the service of the work. And through that work she gave the community a consistent stream of tithings that made all those foibles, for most people at most times, forgivable—tithings of energy, self-reflection, critique, beautification, and, sometimes more darkly than others, hope. That stream has stopped flowing, signaling that sense of an era ended for many. Where will our portraits come from, now that we've lost this master of human conditions? From us, of course, as they always have, just a bit more informed by her incisive eye. But there's more to that sense of endings than Julia's passing, because she was in many ways a creature of her age, of an age itself passing in which artists were able to scrape by enough to produce work unshaped by the forces of market, if they wanted to, despite being cast a disparaging eye, at least in the U.S., by normalized mass culture—especially poets in that regard, except of course in times of social crisis, when everyone, everyone turns to us. As the twenty-first century blooms its plots of Late Capitalist trappings, there seems to be less and less room for people like Julia Vinograd, less and less support, and less chance for anyone to devote themself wholly to poetry without the agency of class privilege (which seems to have skipped a century) or prostration to funding or marketing. Julia was beholden to none of that, to nothing but her eye, her pen and paper, her next kind meal, and a good open mic, at which she let her world leak out, line by line, to feed the rest of us.

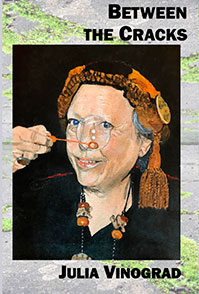

Julia's gone, along with her standard black robes, gold-tasseled medieval cap, rings and beads and bones and buttons, her inscrutable grimace or grin or whatever it was, and those piercing blues, and it feels like the start of an era. Like the new century is finally rung in, casting aside the old, full of poets waving paper and shouting in the streets. Those shouts may echo for a while, but echoes fade, just as Julia's presence will fade, robes and foibles and all; but somehow I can't help but think, and I strongly suspect (call me crazy—you won't be the first) that Julia Vinograd's voice will live on, her voice, her vision, her mind, through those words, those beautiful, fucking, adamant words which, I further suspect, will be lighting up minds for years and years to come. Which leaves us where? Julia knew, so let's let her tell us, with this poem from Between the Cracks, her final book from Zeitgeist Press released after she'd gone into hospital, never to go home again.

STREET SINGER

She sang in the street.

She wasn't pretty, but she didn't need to be.

She sang of everything loved and lost

and never forgotten.

People listened and remembered, almost angry.

"How dare she look at us and understand

without permission?

We wear diapers on our souls,

it's indecent to see so much

and in front of everyone.

Beautiful music is no excuse.

What does she leave us with,

we who have to go on living

afterwards?"

![]()

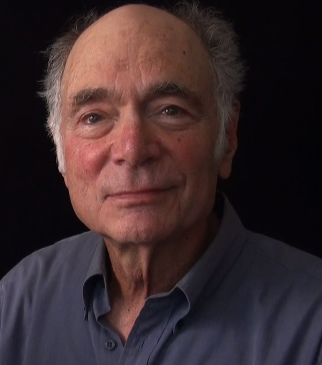

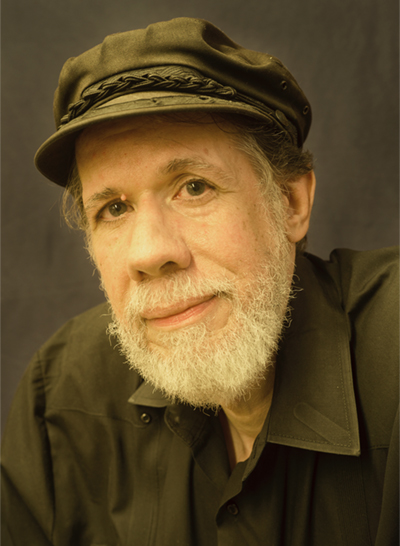

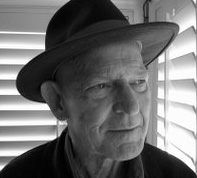

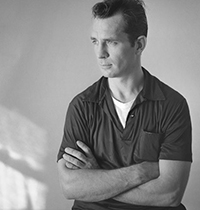

Richard Loranger is a writer of poetry and prose, as well as a spoken word, performance, and visual artist. He is the author of Sudden Windows, Poems for Teeth, The Orange Book, and nine chapbooks, including 6 Questions, Hello Poems, and The Day Was Warm and Blue. His work has been included in over ninety magazines and journals, and twenty-five anthologies, among which are The Careless Embrace of the Boneshaker and It's Animal but Merciful, the online anthology HIV Here & Now, Overthrowing Capitalism Volume 2, Beyond the Rift: Poets of the Palisades, Beyond Definition, Revival: Spoken Word from Lollapalooza, and The Portable Boog Reader. Recent work can be found in Oakland Review #4 and Full of Crow: Winter 2017 Fiction. He blogs on his site, richardloranger.com, and lives in Oakland, California.

— posted January 2019