Fireflies in a Jar

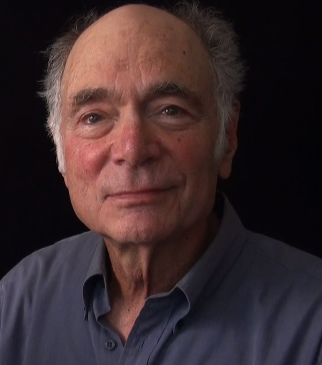

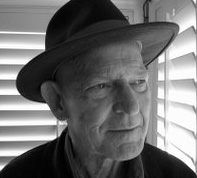

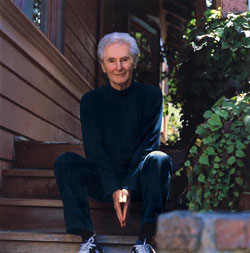

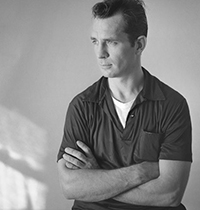

An Interview with Maurya Simon

by Meryl Natchez

MAURYA SIMON HAS PUBLISHED ten full-length books of poetry, each one of them unique. She lived in Bangalore, South India as a Fulbright/Indo-American Fellow. She was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in poetry in 1999. Her awards include a University Award from The Academy of American Poets, and the Celia B. Wagner and Lucille Medwick Memorial Awards from the Poetry Society of America. Simon has been a Fellow at Hawthornden Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland, as well as a Fellow at the Baltic Centre for Writers and Translators in Visby, Sweden and a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome.

Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, TriQuarterly, The Kenyon Review, The Gettysburg Review, The Georgia Review, Grand Street, Agni, Ploughshares, Shenandoah, The Los Angeles Times Book Review, Calyx, New England Review, and in more than two hundred and fifty additional literary magazines and journals. Her poetry has also been collected in more than two dozen anthologies. She is a Professor Emeritus and a Professor of the Graduate Division in the Creative Writing Department at the University of California, Riverside, and she lives in Mt. Baldy, in the Angeles National Forest of the San Gabriel Mountains, in southern California.

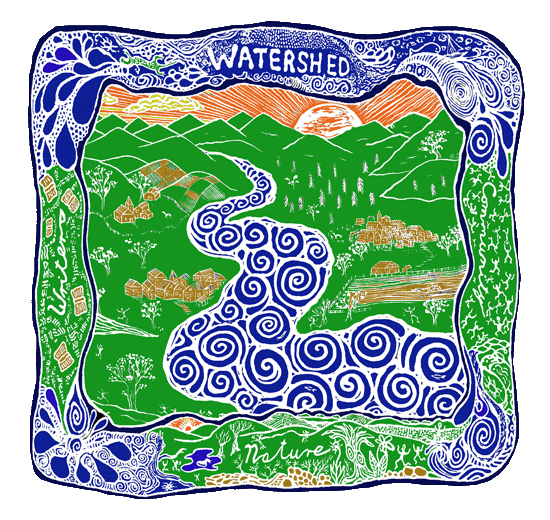

Her most recent book, The Wilderness: New and Selected Poems, 1980-2006, appeared this year from Red Hen Press, complete with beautiful color illustrations of her ekphrastic "Weavers Series" poems, reproduced from the original paintings by Simon's mother, Baila Goldenthal.

Meryl Natchez: My first question for you, Maurya—your work is so accomplished and given your many awards and impressive list of credits—why you are not better known? I was astonished I hadn't heard of you.

Maurya Simon: That's a question I've not been asked before, but that's been hinted at. I think it's partly because I really avoid the limelight. I'm basically an introvert, and I'm terrible at self-promotion. Really, I'd rather clean up the dog shit at the back of our house than put myself out there. Well, this is an exaggeration, and I always love any gathering of fellow lovers of poetry and literature. I think younger poets are brilliant at promotion, with all their expertise with social media, etc.…but I'm really the opposite.

In addition, from 2009 to 2016, I was seriously ill, and I faded from the poetry scene. It's hard to reclaim that space, to get back into the swing of things.

MN: Let's talk a little bit about your recent book, The Wilderness. You have poems from so many different books, with such different styles and focuses. Talk to me a little bit about your journey—how you selected what you did, and what you'd like people to know about this book.

MN: I think it's important for people to know that I really tried to go on a different journey with every book, not just thematically, but also in terms of the shapes and sounds and craftmanship of the poems. While there are certainly specific themes that run through all of my books, I really tried to explore new areas of myself and the world with every subsequent book, and because it's boring to repeat things I already know. I do think writing is an act of discovery.

MN: I certainly think you've been successful with that. There is great variety in the book. Your voice really changes from book to book, and I enjoy that.

MS: Thank you. I think that the book that really varies the most is The Raindrop's Gospel: The Trials of St. Jerome and St. Paula, in which I composed long narrative poems. I think of myself as a lyric poet, and though these poems are still lyrical, their narrative form is a real departure. The part of writing that book that I loved most was doing its research. It was just fabulous to read, in translation of course, St. Jerome's letters from sixteen hundred years ago. St. Paula's letters to him are all lost to us, but you can discern what she said to Jerome from his responses. It's a fascinating love story, and one that the Catholic Church doesn't acknowledge, or perhaps de-emphasizes. I think I found my voice anew with that book.

MN: I think I was also particularly drawn to your poems about India.

MS: I think those poems begin to reflect a kind of spiritual quest. I don't know if that's what you're drawn to, Meryl, and/or perhaps to some of the exotic South Indian locales. When I went to India the first time in 1971, it was very different than it is today, almost fifty years later. It was extremely poor; there was no way to escape seeing horrible suffering every day.

I went back to India last January, and I was astounded at how much more affluent the country is now. You no longer see corpses lying on the street, and that was commonplace when I was there in 1971. I think part of the power of that earlier experience for me was to confront the human deprivation and suffering that we're largely protected from encountering in America. We don't see lepers walking down the street, nor people so destitute that they're naked, diseased, and utterly forsaken.

I was twenty when I first went to India. I was shocked there into an awareness beyond my comfort zone, beyond my middle-class American upbringing, and that changed me profoundly. My book, The Golden Labyrinth, and some of the India poems that made their way into other books, reflect that inner turmoil. At the same time, India is a country steeped in the sacred, so it's a place where you see different religious cultures ubiquitously engaged in the daily offices of the spiritual life, which is quite moving. And it's a place where you have these incredible juxtapositions of beauty and horror, and of great wealth and great poverty, side by side. While in India, I was continually assaulted by truths about the world that we're pretty much sheltered from in America.

MN: When you came back from India, you were still in your twenties. Tell me a little about your journey through the world from then on. Actually, let's start further back, because you grew up partially in Europe, didn't you?

MS: Yes, we lived and traveled in Europe from the time I was four till I was about eight, about three-and-a-half years. My parents were completely disillusioned with the fifties Eisenhower years in post-war America. My dad had been a friend of James Baldwin in New York, and when Baldwin went off to Europe, my dad really wanted to follow him. It took us a few years to do so. My dad was a veteran and a musician and composer, and he thought he could teach music at Army schools in France and Germany when we needed money, which he did. So, off we went (in 1955), and we had this great life in Europe for several years. My sister and I didn't attend school, but we learned about European history, art, and science by going to cathedrals and museums and monuments. We learned to read by devouring Tin Tin and Archie comic books. We had a wonderful and unconventional education. My sister and I both spoke French by the time we left. I spoke a little Italian, too. We lived for a year in Fontaine le Port, in Maurice Chevalier's summerhouse.

I wrote my first poem in Paris, and I think that's when I decided to be a poet. Such a vocation seemed possible to me, even at the age of five. One day we were walking down the Champs Élysées, and there happened to be a royal wedding for which the city had cleared the whole avenue. The spectacle was like a fairy tale—with white horses and a gilt carriage, the bride and groom dressed sumptuously—and my five-year old self thought it was magical. And when we went back to our dark, cramped apartment, I wrote a poem about the wedding as a way to hold onto that experience. I thought "This is how I can keep this. I can preserve this experience forever, if I write it down." That poem was a talisman for me, a seed, for I felt I suddenly had this power to preserve something beautiful and momentous and illuminating—like fireflies in a jar or bees in amber.MN: So how did your journey evolve from there?

MS: Well, both in Paris and back in the States, my parents had a group of Bohemian friends—artists, dancers, musicians, and writers—including musicians from north and south India. My father had a lifelong love of Indian music, and he wrote his PhD dissertation on South Indian devotional (bhakti) music. So, as children, my sister and I were constantly surrounded by fascinating people. And as much as I loved science, being around artists and writers and actors and singers made me think that the creative life was the only life I could have.

So fast forward, we came back from Europe; we ended up in Southern California, where we lived, for the most part, a very bourgeois life in Hermosa Beach. But I was blessed because my parents loved to read. They had amassed poetry books by Dylan Thomas, and Dickinson, Tagore, and Whitman, and I loved going through their bookshelves. I think I read Leaves of Grass probably 200 times by the time I was ten. I had no idea what he was talking about most of the time, but the music of his language hypnotized me, so that was an important influence.

Then I had wonderful teachers along the way. I had a high school teacher, James Van Wagoner, who was a poet himself and who nurtured me—and poet Mark Jarman, who was a year behind me. Van Wagoner saw something in us and gave us special assignments. He assigned us specific poets to study, and he gave us difficult writing assignments, both analytically and creatively. I was a painfully shy student, so shy, that it wasn't until I was in graduate school that I raised my hand in a classroom for the first time. And if someone called on me in class, God forbid! So, having someone in high school who believed in me made all the difference.

Then in college I had some terrific teachers, Richard Tillinghast and Robert Grenier at Cal, then at Pitzer College I studied with Bert Myers, who was an amazing teacher and poet, and with Robert Mezey—both were such excellent mentors. Mezey taught me about prosody and how to scan a poem, and he gave me the traditional toolbox of poetic craft, which is indispensable.

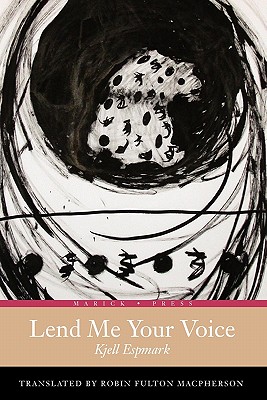

Bert expanded my awareness of American poets, and opened up the world of international poetry for me—I just hadn't previously known about these vital and amazing and essential poets—Naomi Replansky, Louise Bogan, Matsuo Bashō, Yosa Buson, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Czesław Miłosz, Anna Swir, Gabriela Mistral, Octavio Paz, Pablo Neruda, Fernando Pessoa. I'd never previously heard of these poets, and Meyers profoundly extended my knowledge of the broader world of poetry.

I had Bert Myers as my professor during the last year before he died; he'd contracted lung cancer. Amazingly, he asked me to take over his class, towards the end, which I think is the greatest honor anyone ever bestowed on me.

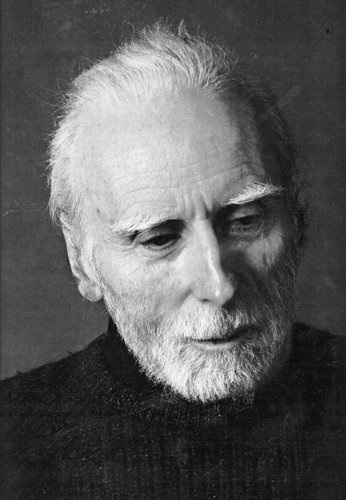

Then I had Charles Wright as my professor in graduate school, and he was another incredible mentor. He gave me permission to investigate and explore the sacred in my work, perhaps because he does this so brilliantly in his own work. Not many American poets were (or are) exploring what's sacred in our lives—and I think of Charles Wright as a great questing, spiritual poet.

MN: That is one of the things I love in your work, the openness to the spiritual in everyday life, no matter what the form or where you are. That seems to be a really important thread for you and is very meaningful in your work. So, tell me now a little bit about your first book, and how that happened. How it came to be published.

MS: I really owe my first book to Charles Wright, who was my advisor in grad school at UC Irvine. He supervised my book-length manuscript that was my master's thesis. When I'd completed it, he said, "Well, I think you need to revise it five or ten more times, and then send it to Copper Canyon Press. If you like, after you've done this, I'll write a little note to Sam Hamill [the editor at Copper Canyon Press] suggesting that he read it." So that's what happened: I spent two or three more years revising the manuscript for The Enchanted Room, and then, eventually, it was published in 1986, when I was thirty-five years old.

I lucked out. I've had a lot of different publishers. I never felt I was a prominent enough poet to try a big New York publishing house. But the literary presses are really the heart blood of poetry. They are so vital to the richness and diversity of contemporary American poetry.MN: Before we move on to talk about The Wilderness, tell me a little about your family.

MS: I have a wonderful family, and it includes my husband, whom I met in India in my twenties, and my two grown daughters, of whom I'm extremely proud. One works with terminal cancer patients at the City of Hope Medical Center, which is probably one of the hardest jobs in the world. The other is a public defender who's currently preparing for her first death penalty case and trial. Both daughters are remarkable young women. And it's interesting to me that their careers are as far from poetry as it's possible to get.

MN: That is really exciting, Maurya. I want to finish up with a few words about The Wilderness. Red Hen press did such a beautiful job on this book, including these lovely full-color reproductions for the ekphrastic Weavers paintings by Baila Goldenthal on which your poems are based. Very few publishers would make that commitment for a book of poems. How did that come about?

MS: My friend and colleague, Peggy Shumaker, who also came out with her New and Selected Poems this year, Cairn, also composed a series of ekphrastic poems based on the art of an Alaskan artist, Keslar Woodward. It was a deeply collaborative effort, and she felt very strongly that there was no way to print the poems without including the Woodward paintings, and I felt strongly that I couldn't include the Weaver's poems in my book without the Goldenthal's art upon which they were based—the art facing the poems. We went together to Mark Cull [publisher] and Kate Gale [editor] of Red Hen Press, and we said, "Please, our New & Selected books really must include the art that engendered these poems." And Mark said, "Let me think about it…," and then, ultimately, he said yes. So, again, I was very lucky.

MN: So, what's next?

MS: Well, after the Poetry Flash reading on September 30th, I have a month-long residency at the American Academy in Rome, and I'll be there most of November.

MN: That sounds great. I look forward to the September reading at East Bay Booksellers. ![]()

Meryl Natchez's most recent book is a bilingual volume of translations from the Russian, Poems From the Stray Dog Café. Her book of poems is Jade Suit. Her work has appeared in The American Journal of Poetry, ZYZZYVA, Atlanta Review, Comstock Review, and elsewhere. She blogs at www.dactyls-and-drakes.com.

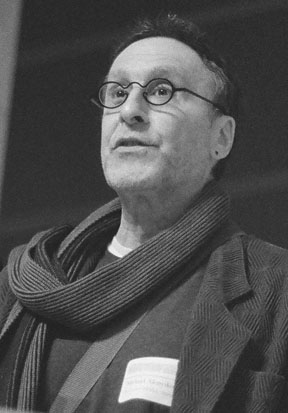

Photo by Jamie Clifford.

— posted September 2018