Flying with "Julia" Poems: Julia Vinograd (1943-2018)

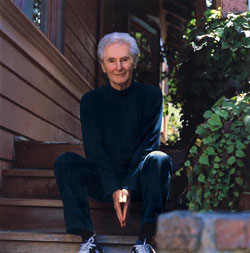

by Richard Silberg

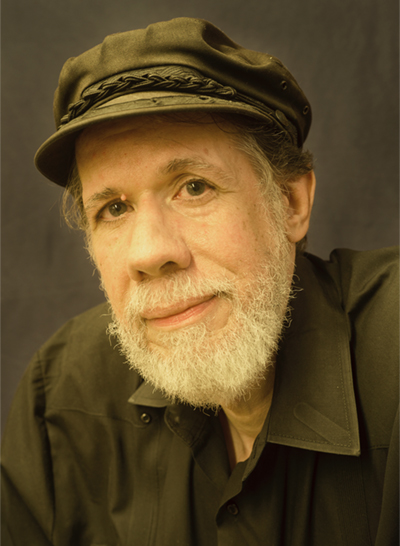

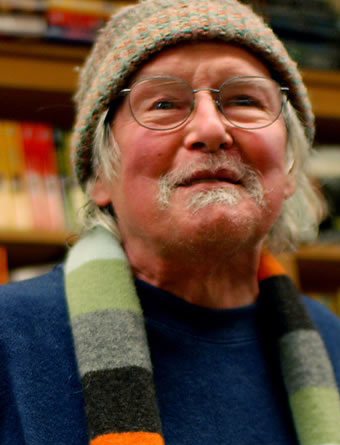

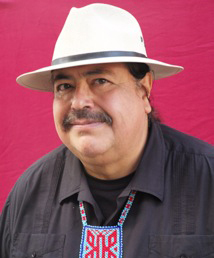

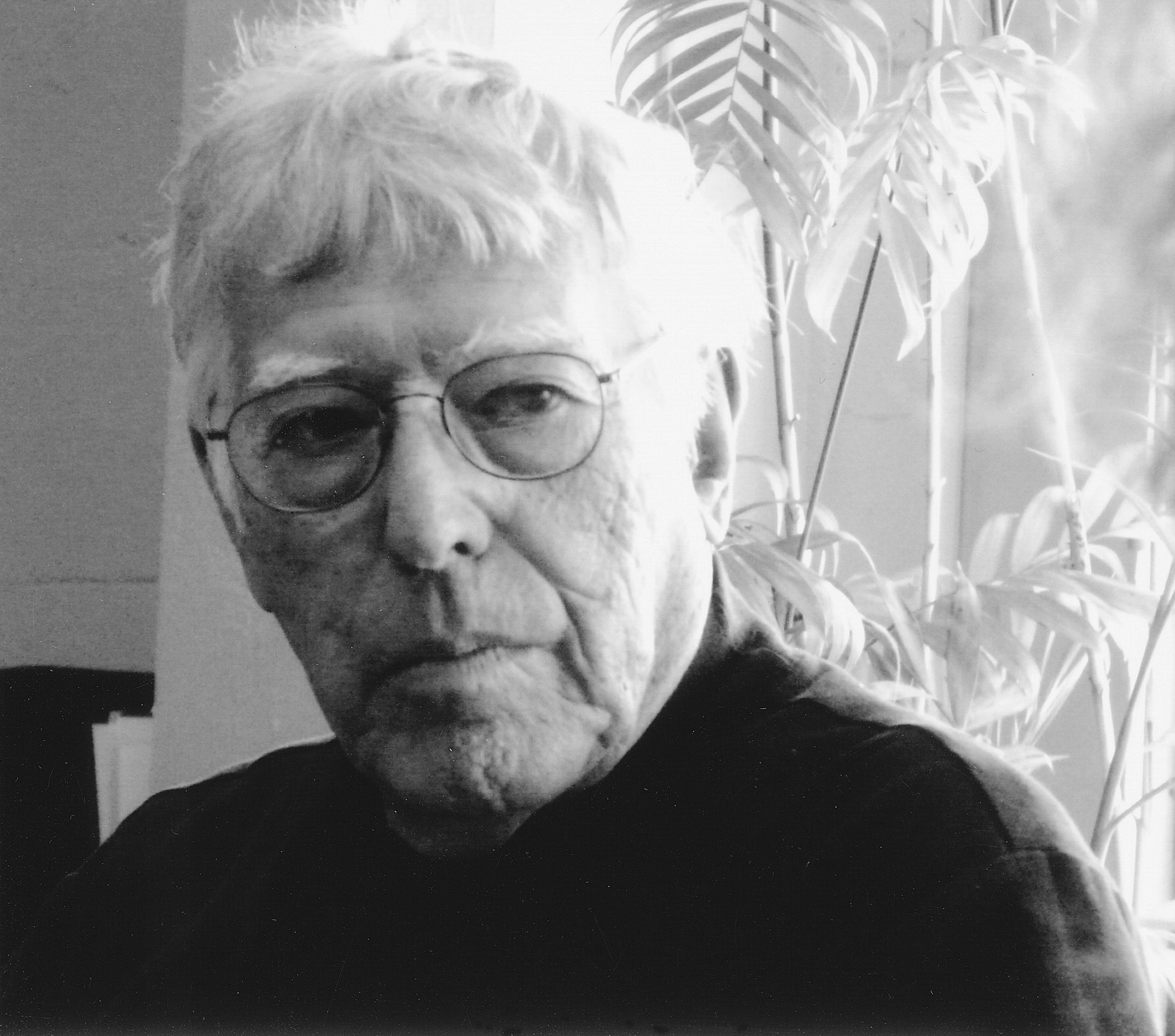

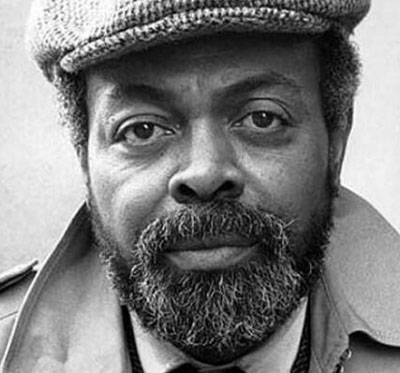

JULIA VINOGRAD, LOCALLY FAMOUS as 'the Bubble Lady of Telegraph Avenue', and 'the unofficial Poet Laureate of Berkeley', died on December 5 at the age of seventy-four. The cause was colon cancer, but she died reportedly peacefully. It's the passing of a perversely fruitful, mythically circumscribed, generous creator.

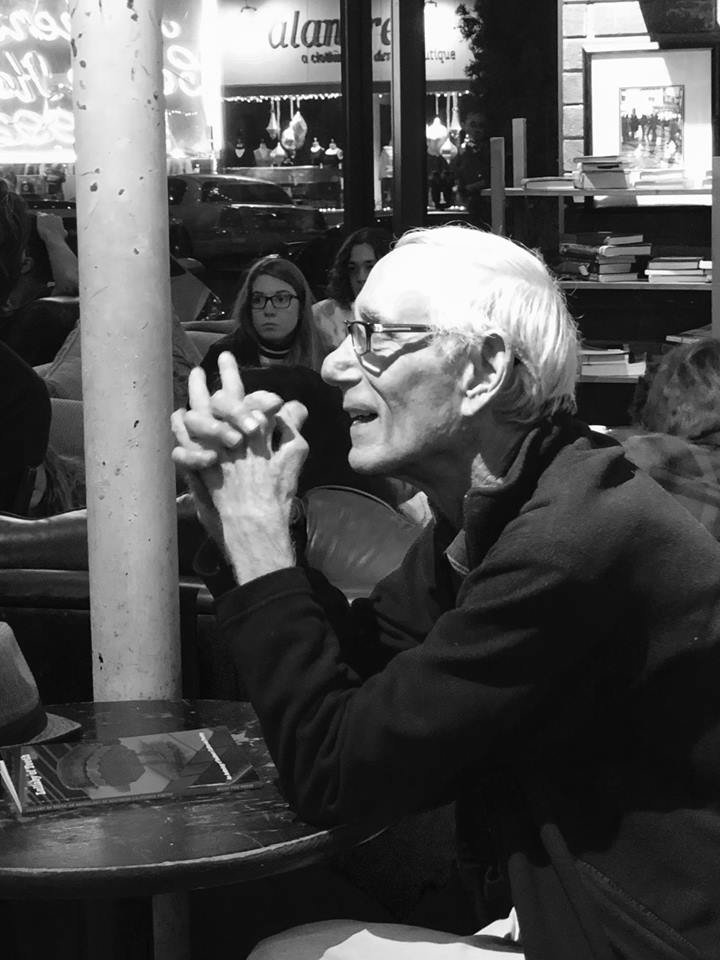

I can't remember when I first met Julia; it seems as if I had always known her. We were both poets and among the tribe of Berkeley people who used the Med, the Caffè Mediterraneum on Telegraph Avenue, as our living room. There was a period for many years when whenever I had a new poem I'd come to the Med looking for her. She'd show me her new poems—she always had some—and we'd critique each other. Ours was a poetry friendship of mutual admiration and mutual recrimination. She felt that my good poems came when I accessed the tough guy she sensed within me, when I wrote, in short, in the punchy street style she had immersed herself in and not what she considered my "academic poetic" stuff. My critique was really the obverse, that she wrote too many of what I called "Julia" poems, tales, portraits, exposés of East Bay street life, its piquancies, ironies, and bottom-up truths, and not enough free flying poetry, work that cut loose the scenic and went to larger more universal themes and modes.

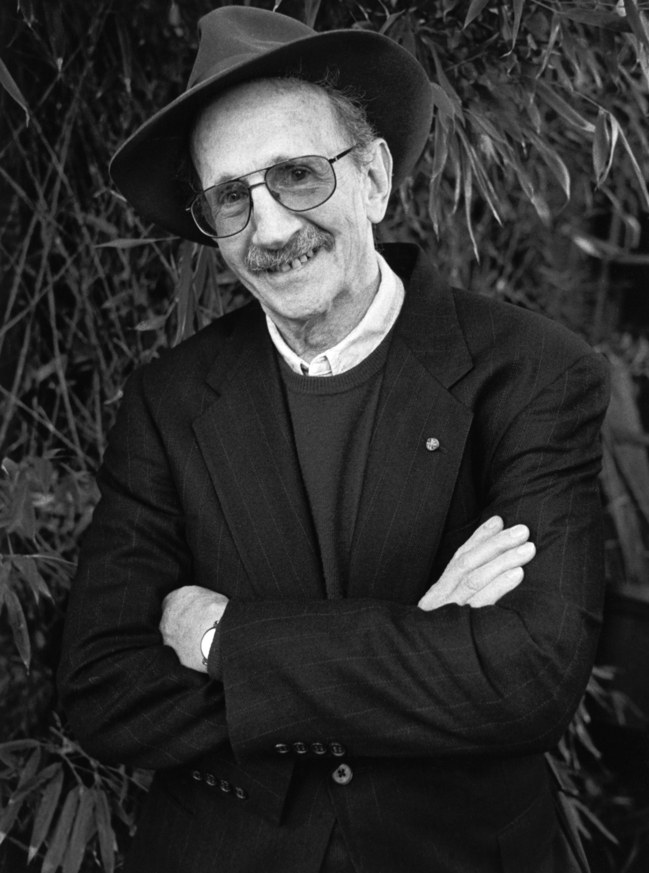

Because Julia was genuinely talented. And she had had the best of poetic educations, a BA from UC Berkeley and an MFA from the famed Iowa Writers' Workshop. Even within the restricted life she had chosen she won some wider recognition, a Pushcart Prize and an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation in 1985 for The Book of Jerusalem. But for reasons perhaps known only to herself she chose to close herself off from that wider poetry world and live the life of a street poet, selling her books on Telegraph, at readings, at public events and reading her poems at local series like Berkeley's La Salamandre, and SF readings like the Spaghetti Factory, Cafe Babar, Above Paradise, and others. And she was enormously productive in her chosen mode, publishing seventy [or more] books through a range of publishers including Oyez and Fred Cody, thirty-nine of them through Zeitgeist Press, whose editor, Bruce Isaacson, is a fellow poet, one of the main instigators of the scene at Cafe Babar, and also her friend and literary executor.

Why did Julia choose to, as I see it, restrict herself as she did, when she had the background, the talent and drive, to quite possibly make a much bigger, a "real" poetry career for herself? Julia had had polio as a child; she wore a brace on one foot and walked with a limp. Did that close her down? She wore a kind of sorceress costume, every day for all the years of her poetry life, a velvety black and yellow tassled cap and a long black gown. She gave no evidence in her poetry or her talk of ever having had a lover. So did she think of herself as not quite a human woman, but as something magically other? Even her celebrated bubble-blowing, whose origins are explained in her poem "Beside Myself: How I Became the Bubblelady," relating to her chosen mode of resistance in the People's Park uprising of 1969, and which charmed children and helped her to sell her books, contributed to her otherworldly, fantasy role.

Whatever the 'deeper' reasons, though, she lived a life without most people's rewards and supports, lover, family, paying job; her chosen world was street life and its poetry, bare-bonedly just that. And yet Julia was one of the happier people I've known. "Every day is Julia's birthday," was the snarky quip of the late Beat poet Jack Micheline, out of the corner of his mouth. But indeed it was so. She was steadily absorbed and excited by her writing, the readings, by the other poets, their work and doings. And she was one of the more generous people I've known, always willing to critique, unfailingly honest in her comments, and when she liked someone she was unstinting in her praise and enthusiasm, without a trace of the jealousy and backbiting so common among poets.

She begins to echo for me as the memorable recent dead do. She was a kind of chairwoman at the old Babar readings. That's a good way to remember her right now. Cafe Babar was a genuinely exciting series at that SF jazz bar on Valencia, mid-'80s to '90s, that I used to go to every month or so. Spoken Word was being born. "St-a-a-a-rting," she would always bellow, summoning the poets to the mirrored back room ringed in bleachers, summoning them eagerly to that evening's creation and romance. ![]()

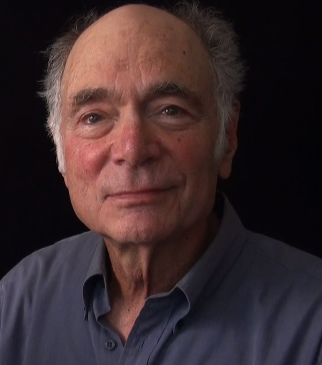

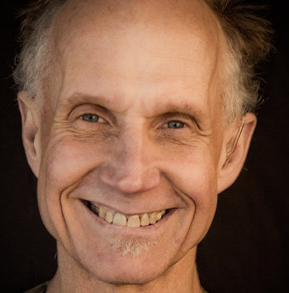

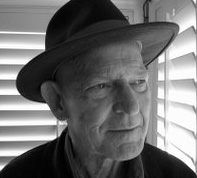

Richard Silberg is Associate Editor of Poetry Flash. His most recent books are The Horses: New and Selected Poems and Deconstruction of the Blues, recipient of the PEN Oakland-Josephine Miles Literary Award. Author of Reading the Sphere: A Geography of Contemporary American Poetry, and other books, he co-translated, with Clare You, The Three Way Tavern, by Ko Un, co-winner of the Northern California Book Award in Translation, Flowers Long For Stars, by Oh Sae-Young, This Side of Time, by Ko Un, and I Must Be the Wind, by Moon Chung-Hee. He lives in Berkeley, California.

— posted January 2019