A Bemused Poet Lost in the Jungle

by Alex M. Frankel

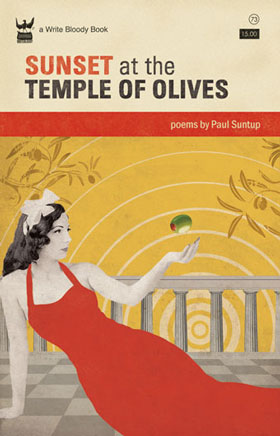

Sunset at the Temple of Olives, poems by Paul Suntup, Write Bloody Publishing, Long Beach California, 2011, 98 pages, $15.00 paperback, writebloody.com, templeofolives.com.

Paul Suntup's Sunset at the Temple of Olives is a volume of poetry that disarms the reader with child-playhouse wit and wistfulness. His unusual poems—many of them prose poems that could just as well be flash fiction—read like Grimms' Fairy Tales before they were revised and softened for children. "Emily," for example, written in a simple, sinister style, is about a little girl who plays house:

…Sometimes Emily pretends she is a burning house.

Emily has a friend named Ben. One day when she was

being a house, burning; Ben rushed in, grabbed

her plastic watering can and poured the wooden water

onto the house.

Later, Ben discovers her—as a "surgeon"—operating on a doll and devouring its heart, and he refuses to rescue her the next time she pretends to burn. He just watches her until she is "a pile of dark ash / on the grass beside her wooden doll without a heart." In only twenty lines and with a few simple, disturbing touches (and no overt bloodletting), Suntup has managed to tell a macabre tale that is half children's story, half pulp fiction.

"Emily" is one of the few third-person pieces in this volume; in most of these poems, there is no escape from the 'I': Suntup's 'I' is a blundering and ruminative boy-man confronted with the cruelty and weirdness of both the external world and his own eccentric fantasies. "Puzzle," a prose poem, begins: "It seems wrong, lying here watching The Wizard of Oz. I should be sitting on the floor in front of the bed with a razor blade, cutting myself into small squares." This insanity is presented nonchalantly, almost in passing; the poem goes on to describe a mosaic made of the poet's neatly carved remains, a mosaic that covers the floor and is adorned with drawings, avocado seeds, plants and an apology. The poem winds up: "Some [of the pieces] I'd cuddle with, and others I'd pound into the carpet with a wooden meat mallet, looking for answers that aren't there."

In a book that contains many fine poems, "Olive Oil" is possibly the book's great poem. It is a memory of youth told in long-lined, spare couplets:

The toast would taste better with egg, but there aren't any,

so I pour a thimble-sized serving of olive oil on, to make it more

flavorful. I like the taste of olive oil. It reminds me of the time

when I was eighteen and jumped clear over the hood of my car

because I could. To be more specific, olive oil is the part where

I leave the ground and I'm in the air, halfway across. Right then,

before landing on the other side. That's the taste of olive oil.

If his style is perhaps intentionally awkward and prosy at times, it serves Suntup's purpose: he relishes the recreating of life's naked, unguarded moments. Equating the taste of olive oil with that vivid memory of jumping over the hood of a car—and dwelling on it in this luxuriant way—is reminiscent of Pilar's memorable monologue in For Whom the Bell Tolls, in which she convinces those around her that the smell of death can be detected on someone long before the person is dead. This smell is a mixture of a ship's porthole, the embrace of an old woman in a Spanish slaughterhouse, some dead chrysanthemums and a gunnysack. Suntup's quirky poem achieves a similar intensity. By the poem's end, the taste of oil has morphed into Brigitte Bardot sunbathing in Capri, "an impossibly / blue ocean wrestling with the sky in the distance."

We are not sure with Suntup where the child ends and the adult begins. There's something sweet and James Stewart-like about this narrator: he is an idealistic George Bailey wandering through Pottersville disheartened by what he sees, and we are disheartened with him. As he explores the tenderloins of this world Suntup conjures up his own vision of paradise, but it is not Bedford Falls; rather, it is a utopia called Martini:

The children would be shaped like miniature

swords and the women would be made of

glass. In this country beer would be tied to

wooden stakes and burned in the streets.

(from "Martiniland")

The far-off dreamscape of this poem serves as an antidote to the vicious Pottersville realities that assault the poet/narrator. The collection as a whole provides a sanctuary in which the poet can safely tell his secrets, live his bemused poet's life, and above all invent. It's a wonderful Sunset at the Temple of Olives. ![]()

Alex M. Frankel was born in San Francisco and lived in Spain for many years. He now hosts the Second Sunday Poetry Series in Pasadena, California.