Full Circle Rhapsody

by Gary Gach

I Love a Broad Margin to My Life, Maxine Hong Kingston, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2011, 240 pages, $24.95 cloth, deckle edge; Vintage, 2012, $15.00 paper; Audible Audio Edition, $19.95.

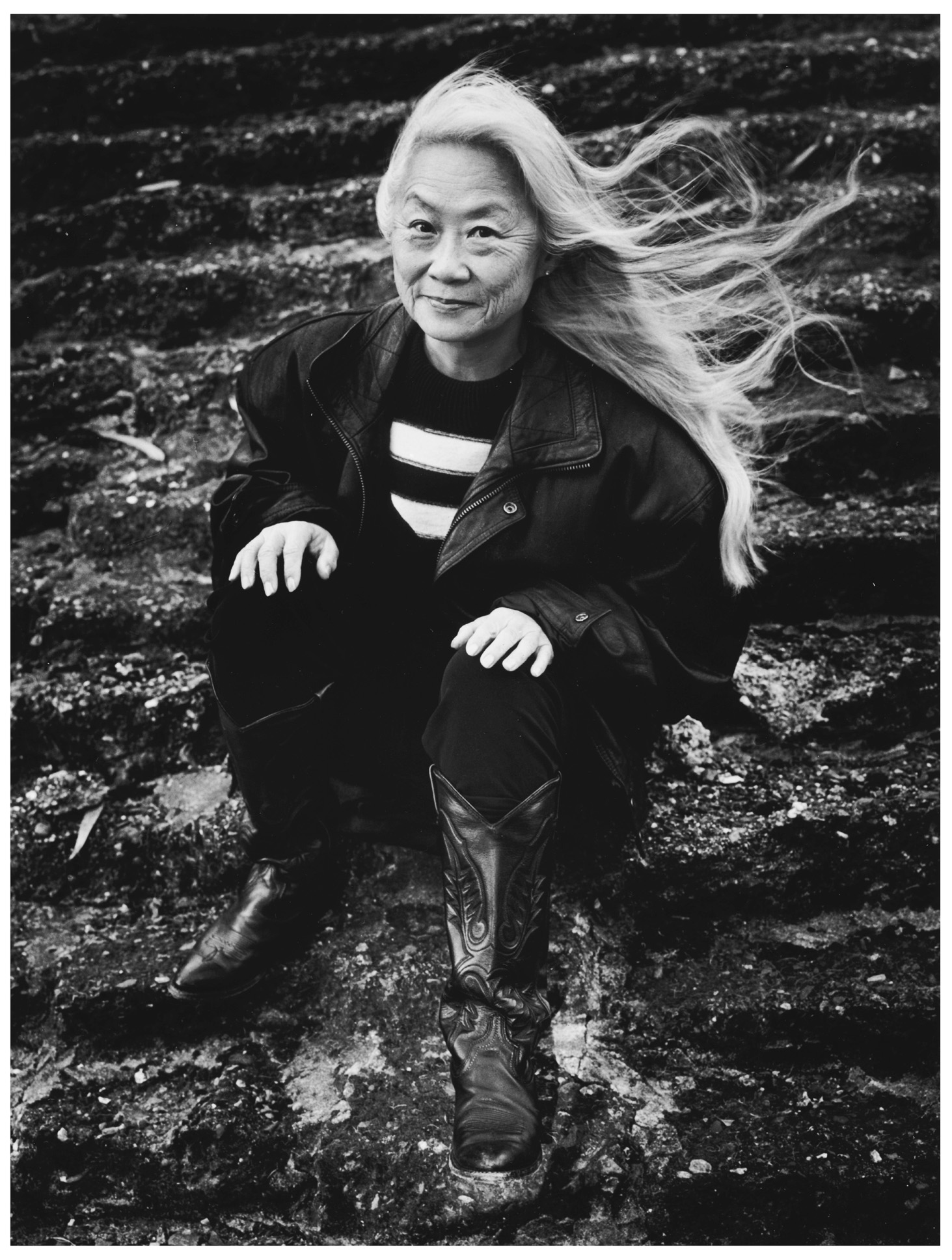

Maxine Hong Kingston has averaged writing one book every decade. By design, her latest may well be her last. A grand summation, it's a beautiful, bold meld of wisdom and compassion, the deep song of a free soul, priceless as dragon's blood. The book is nominally 'about' entering life's winter. For her, that means following whatever the Muse may prompt, like a rolling stone. So she roams all over the store, one last time.

The paperback's now out, in the Year of the Dragon. That's also her birth year. So a dragon can serve as convenient guide. In the West, that's a monster to be slain, but, in the East, an elemental force of nature. A dragon commands a vast reach, delving into deep, dark caves and soaring high to divine heights. With a dragon's fearlessness, the author opens doors where once had been only walls, making barriers into transitions. Transformation, indeed, is an essential nature of dragons.

If this is to be her last book, we might consider it for a moment against her first, The Woman Warrior, gauging the span of dragonhood from head to tail. When Warrior debuted in 1975, a wave of feminism was still at a crest, but Asian American wasn't even a word. And memoir was still mostly a tidy vehicle for the rich or famous to let down their hair, not the province of society's extraordinary ordinary people; the 99 percent. She opened doors for gender, multiculturalism, and the memoir, all in one book. From that moment, she's been not only witness to but also an actor in America's ongoing cultural revolution.

Woman Warrior became the most commonly taught text in American university education for nearly a decade; a noble status, as of a dragon. With its fusion of diverse dimensions, that seminal book showed us the plurality co-existing within any one person. This too reflects dragon nature. With body of snake, crab-like pincers and tiger claws, ox horns and antlers, fish scales, etc. —a dragon is a composite, a living collage. Similarly, I Love a Broad Margin to My Life is testament of an artist, activist, teacher, and seer, all going by the name of Maxine Hong Kingston.

I Love a Broad Margin… opens two weeks before the author's upcoming Big Birthday (her sixty-fifth). Within a day-by-day countdown, she celebrates unexpected happenings and memories, incident and commentary, panorama and detail, bopping around like an extended jazz solo, or zen calligraphy, a mind in motion in the world. Not bound by borders, dragons can leap across realms of time and space in the blink of an eye.

For all its delightfully unpredictable, sinuous, dragon-like noodling—I Love a Broad Margin… is grounded along the strong spine of epic form. From the outset, she also acquaints us with the registers of her fluid voice, learned first from her mother's "talk-story." Such colloquial flow (arguably established in modern literature by Louis-Ferdinand Céline) takes a good ear and enormous discipline, so as to sound effortlessly spoken yet solid, fresh yet lucid. Having spent most of my life in a largely Chinese American neighborhood, I can attest to her getting in print so much of the music of Chinese American speech.

Please listen to these opening lines:

I am turning 65 years of age.

In 2 weeks I will be 65 years old.

I can accumulate time and lose

time?…

…

I am often looking in mirrors, and singling

out my face in group photographs.

Am I pretty at 65?

What does old look like?

Sometimes I am wrinkled, sometimes not.

So much depends upon lighting.

She starts with a direct, declarative statement, plain and simple. But it's like the diction of schoolbook English primer. ESL. (And she's taught high school English.) She bends it, as if See Spot run… Run, Spot, run… were point of departure for jazz riff. That is, she repeats the initial statement with slight variation in pitch, and tone. Then, there's a nineteen-line-long counter-theme, omitted above, in which she notes she's writing this in the dark, just like her mother:

…Who was she writing to?

Nobody.

This well-deep outpouring is not for

anything. Yet we have to put into exact words

what we are given to see, hear, know.

(page 4)

From credo, she switches back to self-portrait, modulating from profound to funny —then onwards into three more pages before the stanza ends on a two word poem: "Pure nothing." For all her leaps, she invariably lands poised squarely, like a cat on all fours. And a new vista opens with the next stanza: the sudden funeral of John Mulligan, who'd written Shopping Cart Soldiers in her writing sangha for veterans. Within life passes death's invisible messenger.

And, yes: poetry. In fact, it's a single 225-page poem. (Ain't life like that? One long poem?) The book practically reads itself aloud, parsed in sturdy four-beat (pentameter) lines. It's like a waterfall, from which extracts are random and futile. (The audio edition's won two awards.)

Reading from it, in Hawai'i, she joked that the publisher is keeping secret the fact of it being poetry, marketing it instead as a memoir, since they know poetry doesn't sell as well. Well, it won't spike sales to say I Love a Broad Margin… ranks alongside the great long poems of our time and times—Four Quartets, Helen in Egypt, Of Being Numerous, Paterson—and on out to such contemporary long-form practitioners as Sharon Doubiago, Jack Hirschman, Joanne Kyger, Nathaniel Mackey, Leslie Scalapino, Ron Silliman, Jack Spicer, Paul Vangelisti (to name but a few from the left coast alone).

It's easy to overlook her craft, given how artless it can seem. She can leap across an ocean in the blink of an eye. I Love a Broad Margin… embarks from home (California) to homeland (China), and back. In the process, it dances across time, from prehistory to postmodernity and New Age. And it melds fiction and nonfiction, memoir and essay, into a whole larger than the sum of such parts.

To elaborate that previous paragraph, a digression is in order. As with previous work, her scenic vision is built up in sections, like a vast scroll divided into panels. Woman Warrior, for instance, was five interlocked stories. Although her prose style is simple—declarative, direct statement—her formal arrangements can be innovative, in keeping with her often uncommon topics. Even if her clever, combinatory gift flies under the radar of most critics, her style does prove to be highly engaging. But I suspect her sometimes unusual formal arrangements are partly why The Fifth Book of Peace, her previous offering, has yet to receive more recognition.

The Fifth Book of Peace, her magnum opus, took fifteen years to write; James Joyce's Ulysses only took ten. Structured upon the four elements, it's also meta-fiction, in which the book we're reading is, on one level, about the author writing the book as we're reading it: an appropriate form for what's more pointedly, and elusively, about peace and peace building, creating a road where none appears by going on ahead, step by step.

Updating her story, I Love a Broad Margin… consolidates and builds upon such strategic vision. Quoting Thoreau for its title, she acknowledges she too writes, as he did, in a casita (little dwelling) of similar size and proportion. It also give us an opportunity to consider precedence for her shape shifting: Thoreau, a reader of the Bhagavad Gita and the Lotus Sutra, influenced Gandhi, who was an important influence on Dr Martin Luther King, Jr., whose speeches were memorized by heart by the kids in Tiananmen Square, whose demonstration was echoed again in Tahrir Square.

And it's interesting to consider poetry and memoir in terms of East and West. For millennia, China ruled poetry. Today, Xi Chuan and a couple other poets in China are keeping the faith, yet poetry's everywhere now. But memoir isn't on the Chinese literary menu. Saying "I" isn't prominent in a collectivist culture. Plus, as the author tells us in correspondence, perhaps "memoir has been perverted for the Chinese, having to write all those fake autobiographical confessions during Cultural Revolution. So sad." How generous for this great author to give us of herself manifest through different modes, like a rainbow. And it's apt, given the spectrum and reach of her well-spent life.

So—having digressed—we see I Love a Broad Margin to My Life's overall trajectory is a journey, to the East and back, as connection with ancestors, and descendents, in the present moment. This takes various vantage points. After her diary-as-overture has rung its variations on "Maxine Hong Kingston" as both author and character, observer and actor, she substitutes another figure as she watches over. She enlists her fictional persona Wittman Ah-Sing as protagonist, in heading back to China. He's familiar to her readers from Tripmaster Monkey. Doesn't his very name conjure up a mash up of West and East? With him, we meander through primal human activities…of spirit…art…and farming. Then, resuming with the author again as her own persona, I Love a Broad Margin… makes the personal political: a visit to contemporary Vietnam, in the midst of which she flashes back to her demonstration and arrest at a huge pacifist demonstration at the White House in 2003. Further peaks ahead are pilgrimages to her father and mother's ancestral villages, each revelatory.

Finally, we arrive back home, full cycle, renewed—like the ink-brushed circle (enso), zen logo, symbol of no symbol, that almost-nothing wherein we might see everything, in an instant. (Or like a dragon swallowing its own tail?) The book's glossary (Chinese and Hawaiian, plus Vietnamese, Spanish, and Native American) defines it as symbolizing "the moment, the all, enlightenment, emptiness."

So Maxine Hong Kingston vows she's laying down her pen. Retiring, warriors hang up their sword. It's also a universal mythic pattern: journeying out into the world for experience, then disengaging from worldly hang-ups, and coming home as return to one's true nature. There's a majesty and profundity here reminiscent of Shakespeare speaking as magician Prospero at the curtain of his final play. Here are the final nine lines:

I've said what I have to say.

I'll stop, and look at things I called

distractions. Become reader of the world,

no more writer of it. Surely, world

lives without me having to mind it.

A surprise world! When I complete

this sentence, I shall begin taking

my sweet time to love the moment-to-moment

beauty of everything. Every one. Enow.

The last word, as in it "would be paradise enow," hearkens to a classic, popular intersection of West and East, Edward FitzGerald's translation of Omar Khayyam. In and of itself, it's a one-word poem. A mantra. Enow. (And how!) —En-joy! ![]()

Gary Gach is author of The Complete Idiot's Guide to Buddhism, third edition (Nautilus Book Award), editor of What Book!? — Buddha Poems from Beat to Hiphop (American Book Award), and translator from Korean of three books of poetry by Ko Un, Flowers of a Moment, Songs for Tomorrow (1960 to 2000) and Ten Thousand Lives. Gary Gach's work has appeared in Big Bridge, Brick, Evergreen Review, Jacket, Hambone, In These Times, The Nation, The New Yorker, Rain Taxi, and World Literature Today. He facilitates two mindfulness practice groups in San Francisco. Visit http://word.to.