The Darwinian Pole

by A.P. Sullivan

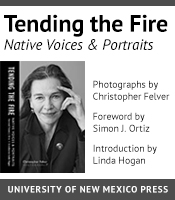

The Cloud Corporation, by Timothy Donnelly, Wave Books, Seattle and New York, 2010, 152 pages. $16.00 paperback, www.wavepoetry.com. In April 2012, The 20th Tufts Awards Ceremony presented the $100,000 Kingley Tufts Award to Timothy Donnelly, The Cloud Corporation, and the $10,000 Kate Tufts Discovery Award to Katherine Larson, for Radial Symmetry, Claremont Graduate University campus, Claremont, California.

Near the end of his autobiography, Charles Darwin describes how, after the age of thirty, reading poetry became for him "so intolerably dull that it nauseated" him. Before thirty, however, he writes that he had enjoyed the work of a variety of poets, mentioning Shakespeare and Milton as well as many of the English Romantics. Darwin then spends a good paragraph wondering sadly why he has lost what he calls his "higher aesthetic tastes." He describes how his "mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts," but he is unsure why this particular disposition of mind has made the enjoyment of poetry impossible. He concludes the paragraph by stating that "the loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature."

Figuratively speaking, Darwin's mind, as he describes it, appears to have become attuned, over the course of his lifetime and through his own efforts as a zealous practitioner of inductive logic, more to measurable light wave frequencies as opposed to a direct experience of color, more to swarms of elementary particles as opposed to, say, a sycamore tree. Almost two centuries before Darwin, the enlightenment philosopher and early contributor to the scientific mindset, John Locke, distinguished between these two ways of experiencing phenomena, the first of which he believed accesses primary qualities, the second, only secondary qualities. The primary qualities for Locke were real, because measurable, while the secondary qualities were entirely subjective and therefore, ultimately unreal, because unmeasurable.

For Timothy Donnelly, in his new book of poems, The Cloud Corporation, it's not poetry that he finds intolerably dull, but the world created by Darwin's and Locke's way of thinking that, in its most current iteration, reduces our greatest longings and "higher aesthetic tastes" to quantifiable brain secretions. And yet, unlike Darwin, there is evidence in The Cloud Corporation that Donnelly is still in possession of his "higher aesthetic tastes," not to mention his sense of humor: "The world tries hard to bore me to death, but not hard enough." The sentiment expressed in the independent clause is all Darwin after thirty, but in the dependent bit at the end, Donnelly makes a strong case for a "fire that our inextinguishable will begins," which is to say, some region in him as yet unfettered by the mechanical, primary-qualities-seeking mind.

Donnelly's best poems in this collection foreground the battle in his own consciousness between these Darwinian, mechanizing forces in his thinking and the fire that for him feels more human and less deterministic. In the book's first poem, "The New Thinking," it appears early on that the Darwinian pole or what Donnelly calls "knowledge" is winning out:

After knowledge extinguished the last of the beautiful

fires our worship had failed to prolong, we walked

back home through pedestrian daylight….

Three tercets after knowledge does this extinguishing act, the narrator feels "fear" and "disenchantment" and a "disease of the will." The "new thinking" of the title is introduced in the third to last tercet with a visit from the natural world. This new thinking the poem clearly distinguishes from the knowledge that has heretofore held sway: "That a sparrow sat for a spell / on the window sill today to communicate the new intelligence." Donnelly's apt choice of the word "spell," playing on its double meaning in this instance, indicates perhaps knowledge hasn't completely extinguished all the fires, that some are like those novelty birthday candles that can't be blown out. The fire also beautifully and stubbornly endures in the whisper of Donnelly's alliteration—not as sound waves (primary quality) but as music (secondary quality).

That my concerns so far in this review have been fundamentally epistemological is not, of course, typical for a review of poetry. However, I have chosen this particular tack because I wish to follow one of the primary courses set by Donnelly's poems—one that reviewers of his work have for the most part overlooked. I say this as preparation for discussing the penultimate tercet of "The New Thinking," which, to paraphrase J. W. Goethe, is an instance of Donnelly's poetry worth a thousand. I quote the whole stanza:

The goal of objectivity depends upon one's faith

in the accuracy of one's perceptions, which is to say

a confidence in the purity of the perceiving instrument.

The poems in The Cloud Corporation wobble between faith and doubt in the veracity or objectivity of human experience. And when Donnelly doubts, he doubts like René Descartes to the very core of doubting. In the poem, "The Malady That Took The Place Of Thinking," Donnelly rightly concludes that if our philosophy dismisses the human beings' capacity to experience reality, sympathy for others' suffering becomes problematic:

With no world to adhere to, there can be no photograph,

no women, no children, and certainly no battalion

shooting when there was nothing there to begin with.

Donnelly's poems that overtly wrestle with this faith and doubt, questioning both, are the most compelling. In these poems he is like some intrepid war reporter who sets up camp at the disputed border between perception and cognition, and then watches the skirmishes. In "In his Tree," he reflects on one of the skirmishes and its "destructiveness":

And I could tear my eyes from none of this, probably

because the mind kept seeing more than an eye

or kept wanting to, detecting in what it landed on

what it did not see but knew, sensing the relation

between things present and between present things

and those remembered or supposed….

When Donnelly chooses the safety of one side or the other, his poems, unfortunately, seem to unfold on autopilot; he seems overly entangled in what he calls, in the collection's last poem, "the circuitry that suffers me." Thankfully, only a few poems in this substantial collection are like this. "Advice to Baboons of the New Kingdom," is one of the few: it's too taken with its own cleverness and too fixed in the condescending irony so popular today—indeed, like many other poets, it is my own default mode. Such cleverness and irony I would identify as, to echo Donnelly, a malady that often takes the place of thinking.

And I would argue a similar malady takes the place of thinking every time we limit reality or truth to primary qualities or other such arbitrary abstractions: Donnelly's fire-extinguishing "knowledge," or "the circuitry that suffers" him. And we do it so often. Here we have Francis Crick, the Nobel Prize-winning discoverer of the structure of the DNA molecule, doing the honors: "You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules." The poet in me thinks not; but of course, Dr. Crick has far more cachet than the poet in me, and yet truth has never been affected by cachet, and I think history will bear the poet out. Anyway, I have no illusions that Crick's reductionist conception of reality isn't at the moment winning the day in the minds of those who call themselves intellectuals. That so many do call themselves this manner of intellectual—taking the side of Darwin-after-thirty, so to speak—may perhaps be a major reason why poetry is so marginalized today, and why we have some poets like Donnelly who seek in their work for more than a primary quality definition of truth that is not at the same time simply subjectivity, solipsism, and fancy, three dismissive descriptors of poetry for far too long.

Yet in his "Between the Rivers," Donnelly seems to propose a way out of these polemics when he begins the poem by wondering "Maybe there's a stage of wakefulness like standing up / on a rooftop I've never quite been able to figure out / how to get to…." In the rest of the poem he describes a stage of wakefulness and clarity at which my little disagreement with Dr. Crick might be sorted out, at which Darwin could possibly be instructed on how to keep his love of poetry after thirty, and at which many of the conundrums of life would evaporate so that everything would become more beautiful. I would not say that Donnelly reaches this stage of consciousness more than hypothetically in The Cloud Corporation, but he does certainly reach a degree of wakefulness unusual in contemporary poetry. Beyond his more conventional gifts as a poet, his stellar metaphors (see stanza five of "The New Intelligence" for a quintessential example) and sonic play, it is Donnelly's wakefulness at the roots and limits of his own knowing that make his work important and memorable and well worth a close read. ![]()

A. P. Sullivan's poems have appeared in Salt Hill, The Literary Review, and New York Quarterly, among other journals. He is a high school humanities teacher in Fair Oaks, California.