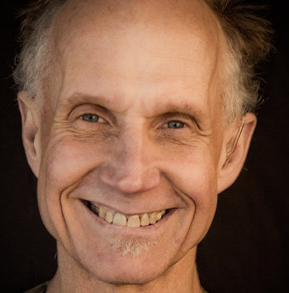

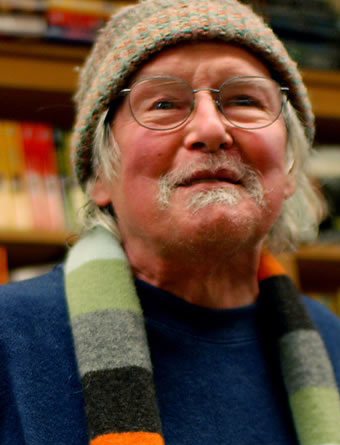

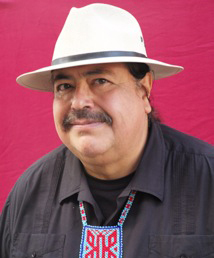

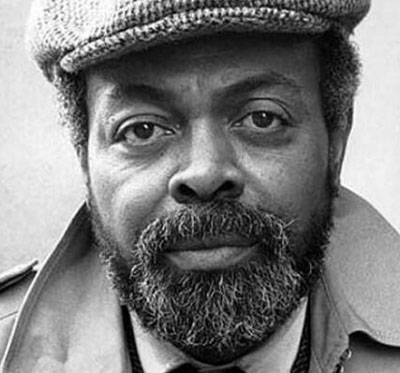

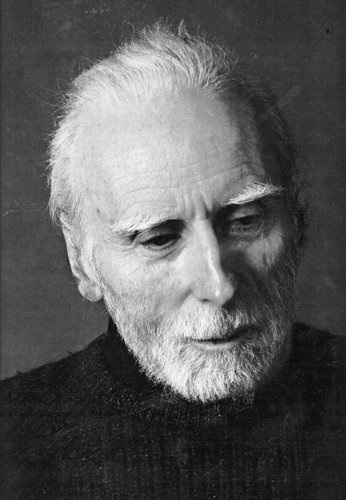

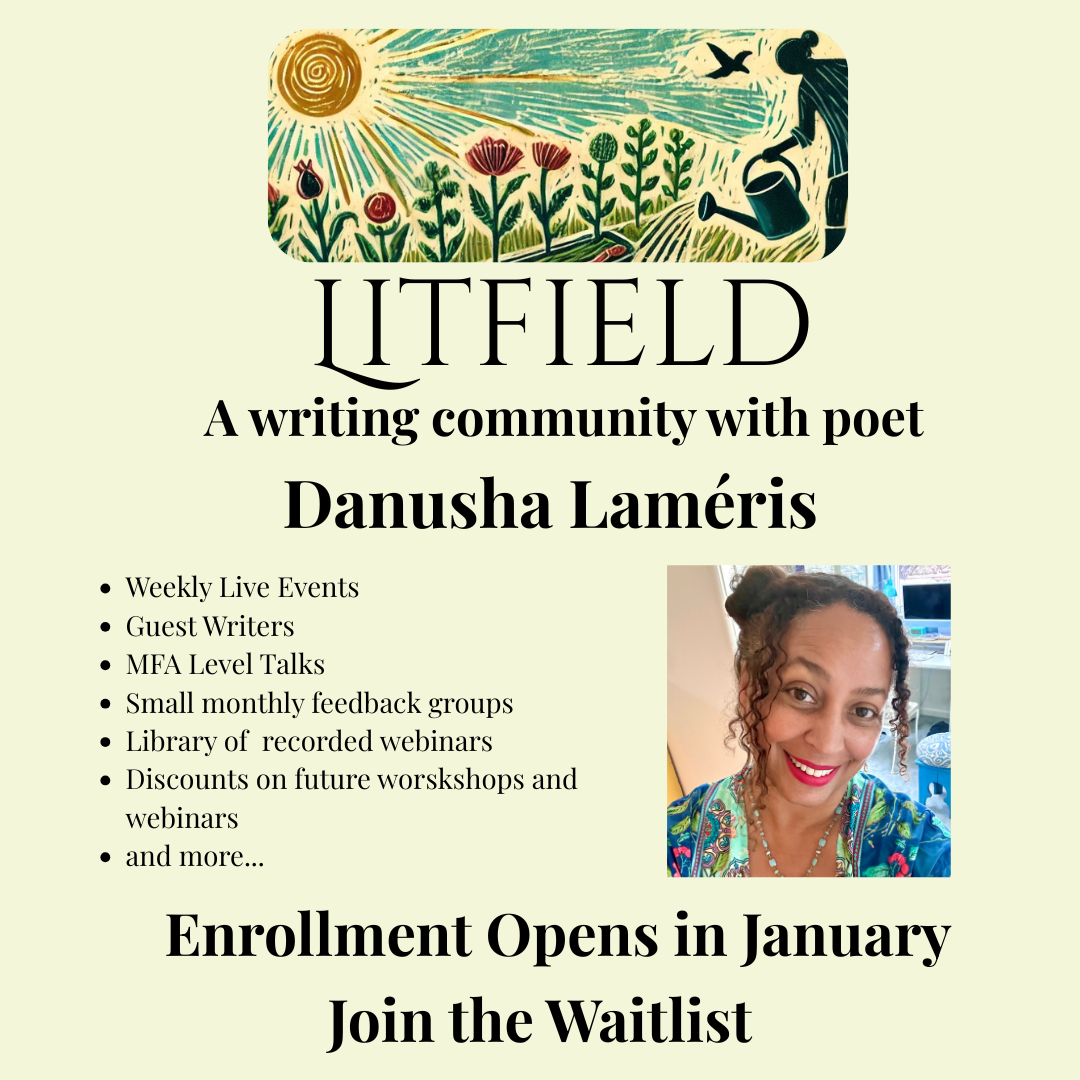

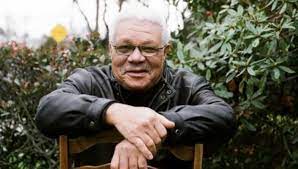

Al Young at the Watershed Poetry Festival, Berkeley, 2010.

The Sound of Al Young Remembered

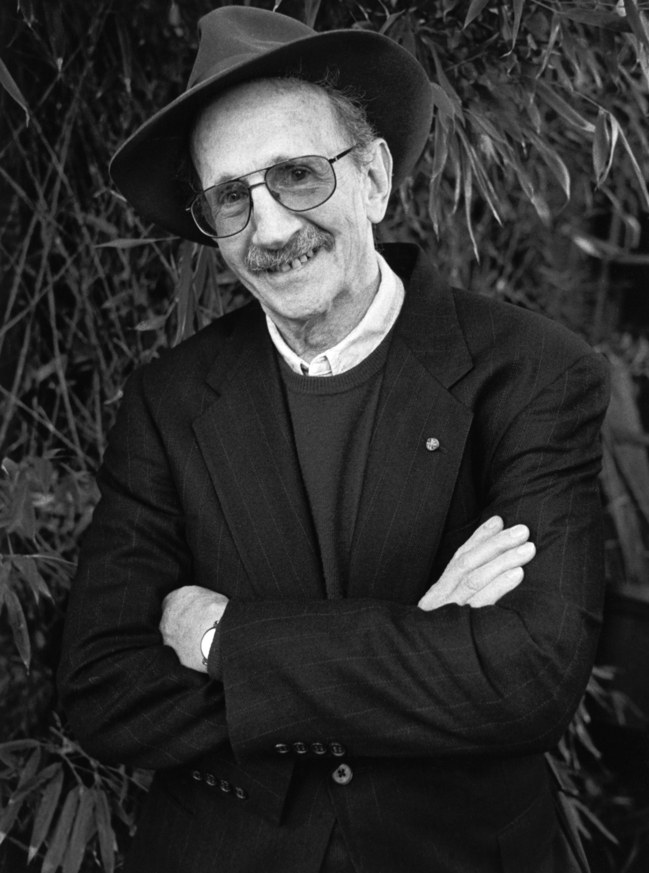

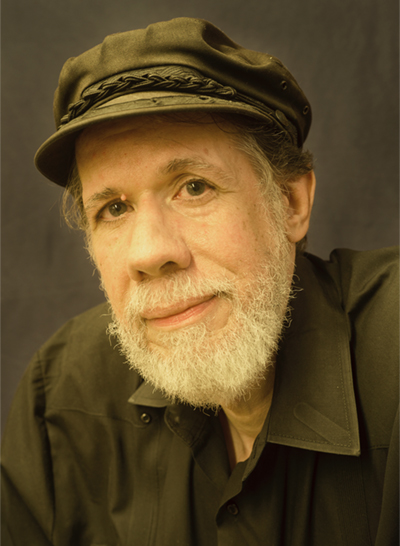

by Jack Foley

In April of 1965 I enjoyed the first of a remarkable and

continuing series of (non-drug-induced) mystical

experiences that I consider, thus far, to be the high

points of my life. I no longer feel compelled, as I once

did, to speak of these experiences directly. I have

learned quite painfully that most people are not

especially eager to hear of such things, and many, in

fact, feel threatened or frightened by them.

…

For me the writing of poetry is a spiritual activity. Poetry

should be the music of love: song, a dance, the joyously

heartbreaking flight of the human spirit through inner

and outer space in search of itself.

…

"In the soul-tunnel of my ear God hummed."

— Al Young

THE MANY EXPRESSIONS OF grief at the death of poet Al Young (1939-2021) are a testimony to the considerable extent that he was an important and much-loved West Coast figure. His friend Ishmael Reed has called him "one of the most underrated writers in the country." "He lived on the West Coast," Reed went on. "The people who receive a lot of publicity live in the New York-Washington, D.C. shuttle area. It's difficult for a writer like Al to achieve prominence with critics who see Northern California as a stepchild of Manhattan."

The musical quality of Al's poetry has been noted—"He wedded poetry and music together," said Sharon Coleman, a poet and instructor at Berkeley City College: "He brought music to poetry in a very integral way"—but, even in the midst of the many encomia he has received, the complex quality of his music or of Al's poetry in general has not been discussed.

Al Young and I were longtime friends—telephone-talking friends—and the man I knew was brilliant, open, ironic, endlessly curious, scholarly, funny, satirical, complicated: multiple. These qualities are all on display in his poetry, but as far as I know they have not been discussed; nor—despite the fact that Al was Poet Laureate of California from 2005 to 2008—has his poetry been recognized as the extraordinary achievement that it is.

What follows is a restructuring of a review I wrote approximately twenty years ago. In it I tried to touch on something of the richness of Al's work. I realized at the time I wrote it that more could have and should have been said, but I felt that this was at least a start. I thought and continue to think that The Sound of Dreams Remembered was a marvelous book.

In a conversation Al told me a story. He had been asked to contribute to an anthology. The contributors were living poets who were asked to name a dead poet who had influenced them and to say how the dead poet had influenced them. The editor asked Al which poet he would like to write about. Al said, "Dylan Thomas." "No," said the editor: "You're going to write about Langston Hughes." And so Al did. Though Al loved Langston Hughes, you will never understand his poetry if you don't understand why he wanted to write about Dylan Thomas.

…

Al was asked to write an introduction to a book of selections from the work of Richard "Lord" Buckley, a popular, sometimes brilliant white monologist whose shtick was to imitate an African-American preacher. In the introduction, Al mentioned—correctly—that Buckley's language was rooted in the language of minstrel shows. You can immediately hear the difference if you listen to Buckley's contemporary, Slim Gaillard, whose speech is genuinely rooted in "Black English" and who is justly celebrated in Kerouac's On the Road. When the Buckley family read what Al had to say, they immediately took him off the project.

Racism has many faces. We see only some of them.

•

AL YOUNG, THE SOUND OF DREAMS REMEMBERED: POEMS 1990-2000 (CREATIVE ARTS BOOK COMPANY, 2001)

Al Young's Heaven: Collected Poems 1956-1990 appeared in 1992. The Sound of Dreams Remembered brings us more or less up to date. Young's title is a deliberate play on a famous phrase which runs throughout Langston Hughes's 1951 sequence, "Montage of a Dream Deferred." Towards the end of The Sound of Dreams Remembered—published fifty years after Hughes's poem—Young writes of

dreams so long deferred that laser-lined Thought Police 100 years from now

still can't decrypt the meaning of their blood;

their blues.

At the conclusion he adds, hauntingly and enigmatically, "light is hard."

The terms dream, sound, blue, and light—particularly light—appear throughout The Sound of Dreams Remembered in various combinations and give Young's work density and resonance, as if, whatever else it may be, the book is particularly a meditation on those terms and all they might mean. "Remembering" itself is a problematical issue here—and not merely because the dream has been deferred. Young admits that memory is "fickle as a feather" ("Memory Meanders, and Sometimes Meows") and asserts that certain poems which appear to be autobiographical are fictional. Identity is primarily the product of memory, and the copy on the back of the book insists that, "Rare among contemporary poets, [Young] almost never uses the pronoun 'I' to refer to himself. His contempt for the unremitting arrogance of the confessional mode is hardly a secret." Yet many of the poems depend for their effect on our sense of the intense particularity of this poet—i.e., of his identity. Worse, Young closes his book with two poems which purport to be the work of "the gifted language poet P.C. Mack"—a suspicious name if ever there was one and, indeed, a yoking together of a pair of opposites or at least of competitors. "As a concluding gesture," he writes,

I have selected two poems from the gifted language poet P.C. Mack's curious underground sensation, The Purina Elegies. And, to restructure credit where credit is due, I must also acknowledge the poet O.O. Gabugah, that African American maverick, who first alerted me to Ms. Mack's poetry.

Anyone who has experienced Tarzan movies of the '40s and '50s is familiar with the term oogabugah: it is Hollywood's version of the "sounds" "native Africans" make. Though O.O. Gabugah rates a section of Young's African American Literature: A Brief Introduction and Anthology—as Young does not—Gabugah, like P.C. Mack, is a totally fictional character. He first makes his appearance in Young's 1976 novel, Sitting Pretty, and Young has used him in various guises since. (Gabugah is the "author" of the introduction to Heaven: Collected Poems 1956-1990, for instance.)

Of course, as O.O. Gabugah, Young can say things he cannot say as "Al Young." Gabugah's most popular work is called Slaughter the Pig & Git Yo'self Some Chit'lins; other works include N----rs with Knives, Black on Back, Love Is a White Man's Snot-Rag, and Takin Names and Kickin Asses. Here is a sample of his verse:

Well, honkyphiles, yall's day done come,

I mean we gon clean house and rid the earth of Oreo scum

that put down Fats for Faust This here's one for-real revolution…

Both O.O. Gabugah and P.C. Mack allow Young to explore aspects of selfhood which could not easily be expressed if he were to say "I." In a way, we might look to this writer not for a sense of "sincerity"—which might easily turn out to be bogus—but for an illuminating dissembling, even play. (P.C. Mack allows Young to function to some degree as a "gifted language poet" and one of Gabugah's poems is "A Poem for Players." It ends somewhat indignantly, "They'll let you play anybody but you, / that's pretty much what they will do.") What Young is doing—and what we experience as we read his work—is close to what he calls in African American Literature "the masked or dual aspect of African American culture":

W.E.B. Du Bois, the eminent sociologist and political strategist, called it "double-consciousness" in his eloquent classic, The Souls of Black Folk: "An American, a Negro, two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder."

Even though these now-classic Negro spirituals spoke at one level of Jesus and heaven and chariots and angels, they also told other stories and expressed other sentiments beyond the surface meaning of their texts.

It is towards such "other stories" and "sentiments beyond the surface meaning of their texts" that Young's frequently enigmatic poetry—particularly this new poetry—is always reaching. Al was acutely aware that in poetry language is what it is but at the same time, like the spirituals he cites, it leaps beyond itself into an otherness that is less "clear," perhaps even less specific than what appears initially but is nevertheless the great power source of what is written. The ability to "hear" that otherness—that music—is what we mean by "the appreciation of poetry."

One of the most spectacular examples of the fluidity of identity—and of the language that expresses identity—is Young's poem, "W.H. Auden & Mantan Moreland." Appearing in Heaven: Collected Poems 1956-1990, the poem takes place in Heaven and is "in memory of the Anglo-American poet & the Afro-American comic actor (famed for his role as Birmingham Brown, chauffeur in those ancient Charlie Chan movies) who died on the same day, September 28, 1973":

Consider them both in paradise,

discussing one another—

the one a poet, the other an actor;

interchangeable performers

who finally slipped backstage

of a play whose cast favored lovers.

"You executed some brilliant lines,

Mr. Auden, & doubtless engaged our

innermost emotions & informed imagination,

for I pondered your Age of Anxiety

diligently over a juicy order of ribs."

"No shit!" groans Auden, mopping his brow.

"I checked out all your Charlie Chan

flicks & flipped when you turned up again

in Watermelon Man & that gas commercial

over TV. Like, where was you all that

time in between? I thought you'd done

died & gone back to England or somethin."

"Wystan, pray tell, why did you ever eliminate

that final line from 'September 1, 1939'?—

We must all love one another or die."

"That was easy. We gon die anyway no matter

how much we love, but the best thing I like

that you done was the way you buck them eyes

& make out like you runnin sked all the time.

Now, that's the bottom line of the black

experience where you be in charge of the scene.

For the same reason you probly stopped shufflin."

The Sound of Dreams Remembered is divided into three sections arranged in reverse chronological order. The opening section, which is also the longest, is "The Sound of Dreams Remembered"; it has the newest poems in the book. Both the second and third sections, "Conjugal Visits" and "Straight No Chaser," appeared earlier as chapbooks.

The opening and closing poems of the "Sound of Dreams Remembered" section are both titled after songs by composer Vernon Duke. Young notes that the lyrics to the first song, "April in Paris," are by E.Y. (Yip) Harburg and the lyrics to the second, "I Can't Get Started," are by Ira Gershwin. In both poems the presence of the song is an extremely important element in understanding the poem and in both cases the songs were written by white, Jewish writers. The concluding lines of Young's "I Can't Get Started" are a kind of paraphrase of Gershwin's lyric:

In my bourgeois house, by my brand new pool,

my late-life Ph.D thesis about to be a book,

my savvy stock portfolio healthy and trim

like this new body to which you get

my initial public offering, and Oprah

just left me some choice voicemail.

Tell me, sweet thing, please—how come

I find myself blessed with everything

this system provides, and still I can't get you?

Similarly, phrases from the song "April in Paris"—sometimes slightly disguised—find their way into Young's poem of the same title: "Whom could we run to," "holiday tables," "chestnuts in bloom" (rather than "blossom"). In both cases, however, there is also a "double consciousness" at work. Young's status as an African-American literally "colors" the implications of words originally written by white, Jewish Americans. One wonders what O.O. Gabugah would say about the speaker's "bourgeois house" and his "brand new pool." (In "Tango" Young refers bitterly to "squalid, unwashed bourgeois minds.") African-Americans may well have "everything"—and still not have what they want, may well feel that, despite material possessions, "they can't get started." In "April in Paris," the speaker asserts,

Back home we knew what it was like to be the other—

displaced, despised, imprisonable. We watched and fought.

The colors of loss deepened.

The question of the role of music in Al Young's work is an exceptionally important one. The "Statement on Poetics" at the conclusion of "Conjugal Visits" begins, "Music—with which poetry remains eternally intimate—seems a dead ringer, as it were, for life itself." The statement ends with still another quotation from Vernon Duke and E.Y. Harburg: "After 60 years of listening, I still feel as though I can't get started…" (my italics).

The speakers of the poems "April in Paris" and "I Can't Get Started" are both African American and they are both haunted by the songs "April in Paris" and "I Can't Get Started"—songs which, despite their origin in the largely white world of musical comedy, were often recorded by African American musicians. In a way, Young here is like a jazz musician riffing on songs by white composers—"claiming" them, making them "their own" to some degree. But there is more to it than that: Young is also suggesting that the speakers' conception of the world is like something out of a popular song, that their "reality" is the reality of being in a world postulated by the lyrics of a popular song. What exactly does that mean? Is that the "real" world? Popular songs are simultaneously expressions of feeling and ritualized evasions of the complexity of feeling: they are deliberate sentimentalizations, simplifications; "sophisticated" but often fueled by intense self-pity. Ira Gershwin—perhaps thinking of his achieving brother, George—wrote:

I've been around the world in a plane

I've settled revolutions in Spain

But lately I'm so downhearted

Cause I can't get started

With you.

Popular songs—"standards"—can be a kind of joyous, demotic poetry, but they are also a kind of evasiveness. A person seeing himself in terms of popular songs is constantly generating sentiment but also constantly generating blindness.

The great example of the self as popular song in this book is Billie Holiday—a great artist whose tragedy was to merge almost entirely with the material she so magnificently and subtly expressed. Popular songs are all about our need for illusion—and Holiday becomes a kind of emblem of that need. At the same time, she is also, as the narrator of "On the Road with Billie" insists, precisely "the sound of dreams remembered"—an emblem of what Young calls in the Auden/Moreland poem "the bottom line of the black / experience." Young's poem to Holiday is shot through with references to popular songs—songs Holiday sang: "Stars Fell on Alabama," "I Cover the Waterfront," "God Bless the Child," "I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm" (parodied, since "Sex didn't fix": "You had your songs to keep you warm"), "Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me," "Up Jumped You with Love," "You Go to My Head," "I Get a Kick Out of You," "Autumn in New York," "April in Paris," "Nice Work if You Can Get It," "Small Hotel," "Cheek to Cheek," probably among others. Yet

When the war broke out and opium split town,

up jumped smack, and you and all your hophead

pals went down and copped. "You go to my head,"

you groaned. Where did it all go? Where did you go?

As "I Get a Kick Out of You" suggests, songs, sex and drugs all move towards one another—become versions of the same thing. They are all to some extent subversive and liberating, yet they are also dangerously destructive. Yet what is a person—particularly an African-American person—to do? The poem's narrator remarks, "The War on Poverty, it bombed, but War on Drugs, / it's on a roll."

Young's poem is a brilliant commentary on the complexity of Holiday's world—a world we still inhabit, though the songs have changed. In that world, "success" and "failure" are almost interchangeable. The very "dreams" we pursue annihilate us. At the conclusion of the poem, the "singer" can hardly make a sound: "your heart beat so that you could hardly speak." The reference is to Irving Berlin's song, "Cheek to Cheek":

And my heart beat so that I could hardly speak

And I seem to find the happiness I seek

When we're out together dancing cheek to cheek.

Yet Holiday is hardly finding "happiness." "Remembered," she is an emblem of both triumph and disaster. As Young puts it in "Depression, Blues, Flamenco, Wine, Despair," "You understand the hoodoo stab of hurt":

Black night is falling all around you in the rain.

Dark times, dark times can fix you in the light

of reason, recognition, lasers, pain.

These remarks hardly exhaust the role of music in Al Young's poetry. In Heaven Young writes about "our natural yearning / for heaven," and music plays a role there as well. "There are ways to go to heaven undercover," Young asserts in one poem, and the speaker of another, a "one hundred-year-old jazz head," says, "We music-makers, we time zappers." Light—ever present in this book—is also relevant here. (At one point Young refers to "sounded light.") Young's considerable use of rhyme is also a musical element (there are a number of formal poems, particularly sonnets, in the book) as are his fascinating attempts to sonically mime piano solos. "Snowy Morning Blues," a tribute to James P. Johnson and Langston Hughes, ends

Let the blues roll on. Let snow fall right on time this time

blue, blank, blackening the city-within-a-city christened

in Dutch: Harlem, Haarlem,

Haaaarrrrrlem.

Vermeer, beware.

And "Five," in memory of pianist Bill Evans, has "Roll me in the dirty boogie-woogie of your light"; it concludes,

The smile, the wave the lake makes feels hipper too. Some gig!

Sweet sleep, slide slowly, gently, cleanly

through this bubbling blood of ours.

There are also passages of sheer delight in sound, slightly reminiscent of the early work of the "language poet," Clark Coolidge:

Stopped cold by night, excitement slows. Zigzag,

the jazz of cactus fuzz & insect buzz & lizards whizzing

every which way nowhere & buzzards minding their own

lazy business zooms, the horizon a shining rim-shot.

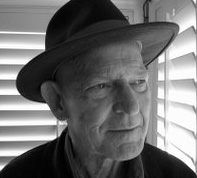

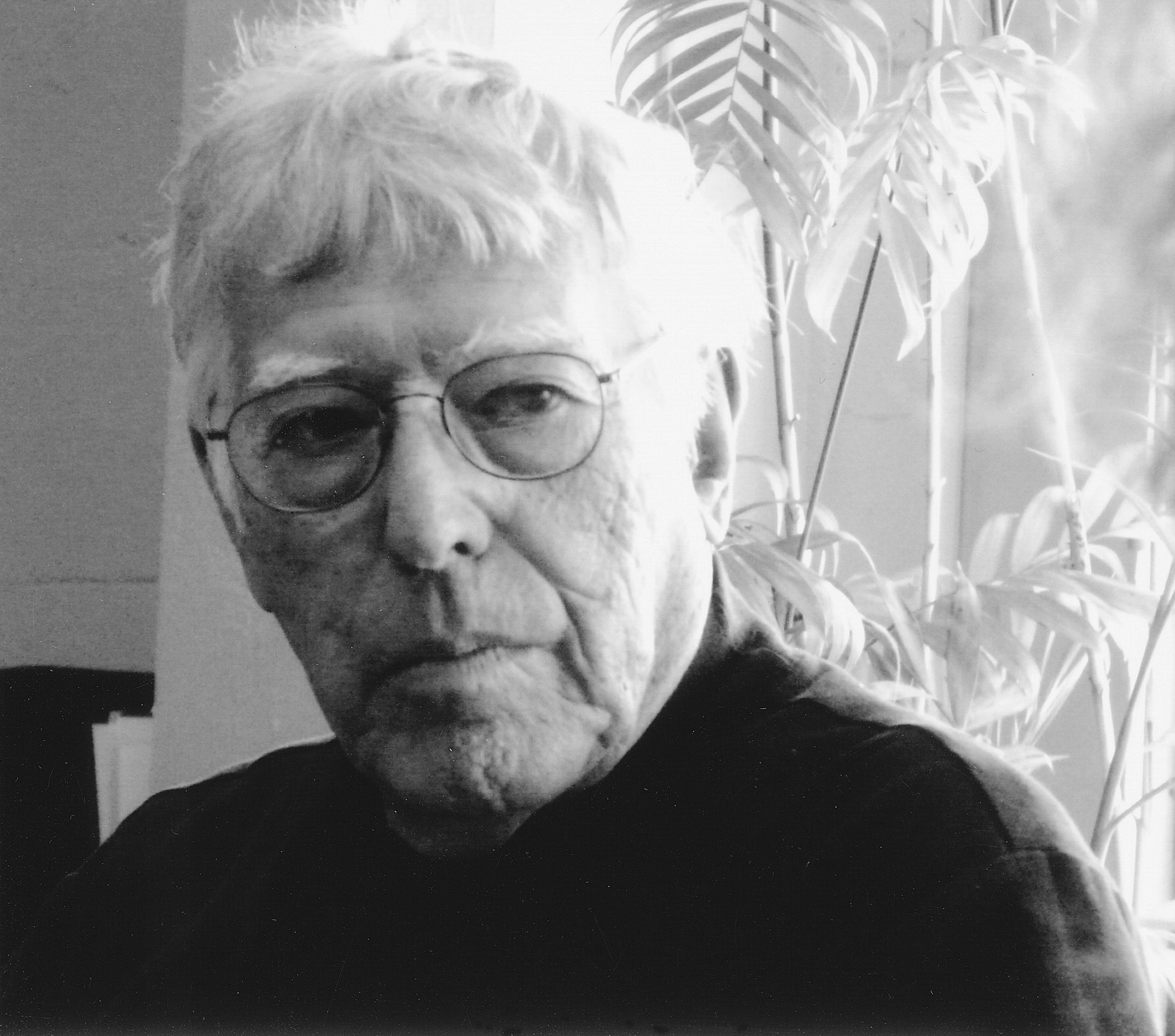

Photo by Jerome Robinson.

In short, The Sound of Dreams Remembered has much to tell us about ourselves, whatever our ethnic or poetic persuasion. "The loveliness of poems is that they keep," Young writes: "the loveliness of lives is that they don't." There is a good deal of surface dazzle, but the poems also stay in the mind and repay re-reading. The book has many provocative observations ("It wasn't the French invented surrealism; it was Americans"). Among its "speakers" are a tomato and a lizard. If you want to know "How the Flower Flourishes," this book can tell you. As O.O. Gabugah says, rightly, "We got to get the brothers and sisters to reading more. Of course, having the pictures in there and the short poems in big type helps."

And he adds,

Since I don't have time for these silly-ass

games—plus I don't read or write poetry,

in the first place, to prove how deep and heavy

and intellectual I am—just give me

somebody that's hitting on the main subject,

which is life. And it's a double treat when that

somebody also happens to be full of life while

they're talking about life. That's Al Young. And

the brother is upbeat; about as upbeat as you

can get and still be living in North America in, you

might as well say, the 21st Century. That's what I

read poetry for: I wanna know what you love,

what you're crazy about; whether it's a certain

hangup or fixation or just being alive or wanting

your freedom from something that's been holding

you down. What I've noticed about too many

well-meaning professional poets is that they're

See No Evil, Hear No Evil, and Evil.

Behind Gabugah's street rhetoric—informing it—one can feel the presence of the tender, brilliant, scholarly, educated, sophisticated, street-wise, vastly amused consciousness that was Al Young: "just give me somebody that's hitting on the main subject, which is life."

One final thing on music. When one reads The Waste Land, one is sometimes daunted by the range of references that extends throughout the poem. Someone remarked that you think you're reading Eliot and then you find out you're reading Baudelaire or Dante—or even Wagner. Eliot feels free to refer to almost anything that inhabits what we might call Western or Classical consciousness. Though Al Young was certainly aware of the meaning of such references, in The Sound of Dreams Remembered he chooses not to refer to Eliot's Western—and largely white-created—books, music, etc. Instead, he refers to that body of marvelous work created in the '20s, '30s, '40s, and '50s, to what we call "The Great American Songbook," work which has in fact been explored extensively by African American musicians. Young's work is as dense and profound as Eliot's or Pound's in terms of his references, but the references are different. It is part of the extraordinary originality of his consciousness. He expected his audience to recognize what "Straight No Chaser" is or who Bill Evans was. The problem here is that the next few generations of poets may not share that knowledge—knowledge that might be called "Al's dream." For them, Thelonious Monk or "Fats" may turn out to be as unfamiliar as Eliot's Baudelaire or Dante. This thought occurred to me because I've been reading a fascinating book, What Kind of Man, poems by the New York poet, Tony Gloeggler. Though definitely an intelligent, sophisticated poet, Gloeggler does not refer to Baudelaire or Dante either; nor does he refer to T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound. Instead, he refers to The Beach Boys, to Bruce Springsteen, to The Shirelles—to rock n roll. Like Al's, his consciousness is inhabited, even formed by music, but it is a different kind of music. For such poets—and despite the range of their reading—Bob Dylan is perhaps as much a "great poet" as T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Pablo Neruda, Langston Hughes, Emily Dickinson. Where is our common culture? What stories do we share? As Al puts it wonderfully, "light is hard."

•

I don't know how to say goodbye to my friend, Al Young. Yeats—a favorite of mine and a favorite of Al's:

Though grave-diggers' toil is long,

Sharp their spades, their muscle strong,

They but thrust their buried men

Back in the human mind again.

And Al: "How the Flower Flourishes":

Unnumbered & floating

technician-free

smooth

a spore unfolding fast

upon pond-like lake surfaces

spread across unlogged zones of time

this colored burst of meaning

leans peeping from her axis

in lighted directions

every first & last one of them

heated

all 360 degrees precisely memorized

enough to become spontaneous

enough to allow the marvelous

to mimick [sic] or memorize herself

![]()

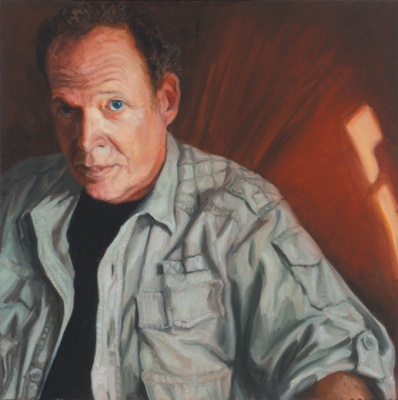

Jack Foley is a poet, critic, and host of KPFA FM's "Cover to Cover" book show. His most recent books are Duet of Polygon: Western-Eastern Poets in Sympathy, a collaboration with Japanese poet, Maki Starfield; the companion volumes, The Light of Evening, a brief autobiography, and "A Backward Glance O'er Travel'd Roads," a biography of Foley's mind; and Jack Foley The True Litterateur, a tribute volume of Foley's poetry edited and illustrated by Shajil Anthru. Foley is a Poetry Flash contributing editor. He lives in Oakland, California.

A previous version of this essay appeared in The Berkeley Daily Planet.

— posted September 2021