The Poet as Provocateur

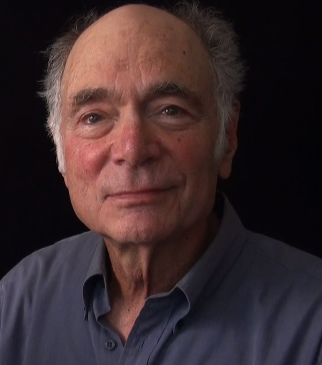

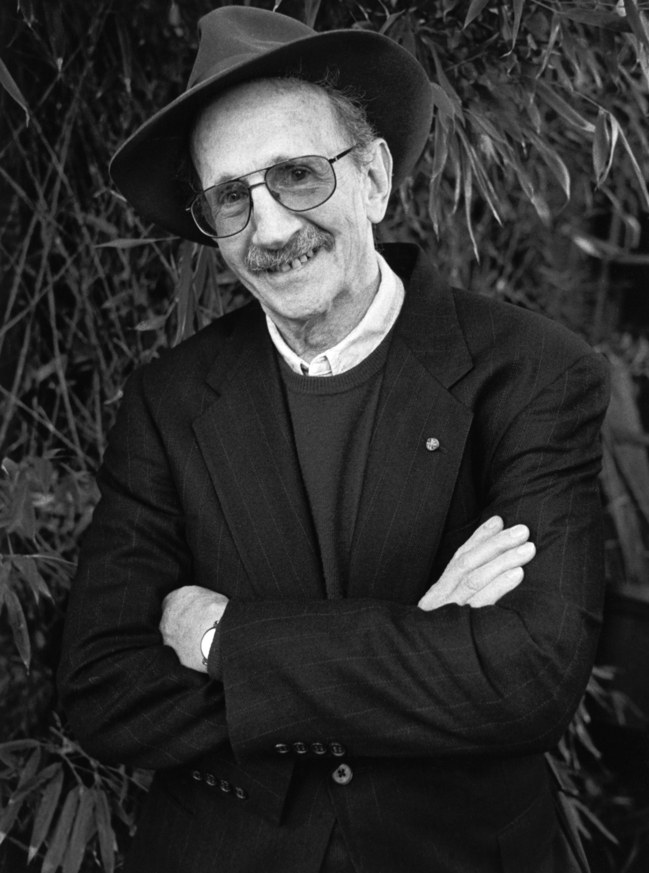

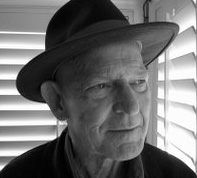

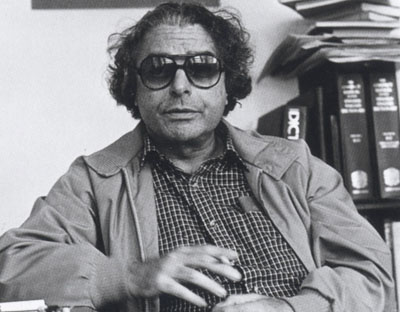

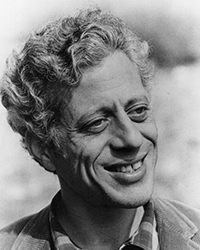

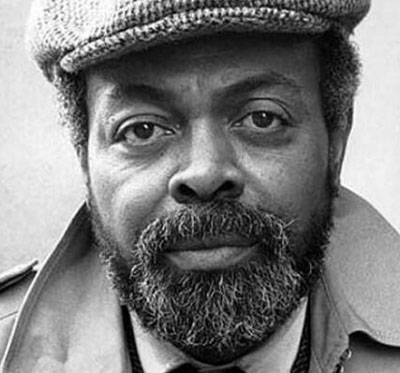

Amiri Baraka (1934-2014)

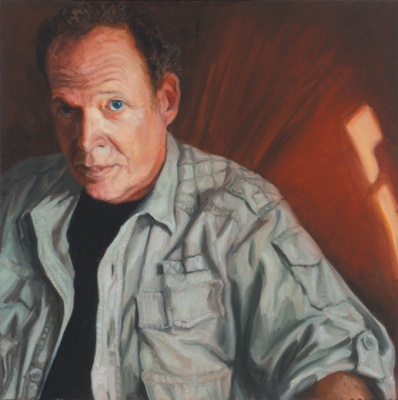

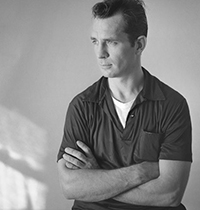

by Stephen Kessler

Amiri Baraka, who died in January at age seventy-nine, was one of the most dynamic, brilliant, furious and infuriating, repugnant and exhilarating, confused and confusing yet illuminating and all-around extraordinary poets I have ever read. Starting out in Newark as Leroy Jones, adopting the first name LeRoi as a young writer and eventually converting to Islam and taking on an even more exotic moniker, Baraka went through many ideological permutations and double-reverses in his long and much-disputed career.

For his forays into race-baiting, misogyny and anti-Semitism he was among the most reviled and denounced writers of his time, but also highly respected if not revered in some circles for his militancy, his activism and most of all his verbal and intellectual gifts and creative energies that enabled him to deliver, on the page and in the flesh, poetry of immense power and imaginative reach.

To hear Baraka read in person to a live audience was to experience poetry as an existential encounter with language at its most vigorously alive. Even if you were taken aback, puzzled, shocked, repelled or otherwise freaked out by its content—and especially if you were moved by its musical beauty and life-or-death urgency and wickedly sharp wit—Baraka’s performance was a captivating example of what poetry can be at its most real: dangerous, incendiary, a sharp attack on complacency and a reminder of the potential explosiveness of the word.

His at times cockamamie cultural and ideological lurches—from Beat hipsterism through Black Nationalism to Islam and thence to Marx-Lenin-Maoism—seemed to me to be a vain attempt to impose coherence on an unruly imagination, a way of grounding his intellect in some system that might give order to his psychic restlessness. Though I sometimes felt he went off his rocker in his diatribes (most famously in the post-9/11 poem that implied some Jewish conspiracy behind the attacks and got him abolished as poet laureate of New Jersey), I was more often seized and moved by his fluency in the jazz-like eloquence of American English at its highest articulation.

Baraka’s presence over six decades on the US literary and political scene, even as a frequent outlaw, injected a most valuable element of intense questioning into an often self-satisfied status quo of various schools and movements and establishments and academic potentates defending their turf. He was the blazing hot sauce on an otherwise ordinary hot dog, the cherry bomb in the cherry coke, the coarse black pepper in the apple pie.

His prodigious production—poetry, plays, essays, fiction, cultural history and criticism, political polemics—made him a force impossible to ignore, and in time I expect the best of his work will far outlast the controversy surrounding its irascible and irrepressible author.

Like his contemporary Newark homeboy Philip Roth, Baraka’s sometimes outrageous contribution to the rich mixture of American letters has given many subsequent writers the courage and the daring to be unapologetically themselves and to advance all kinds of arguments and debates about the range of creative expression available in such a diverse and contentious universe. His example reveals the hazards of fanaticism, but also the transcendent spirit of uncompromised artistic creation.![]()

Stephen Kessler, poet, novelist, and translator, is editor of The Redwood Coast Review and a contributing editor to Poetry Flash.

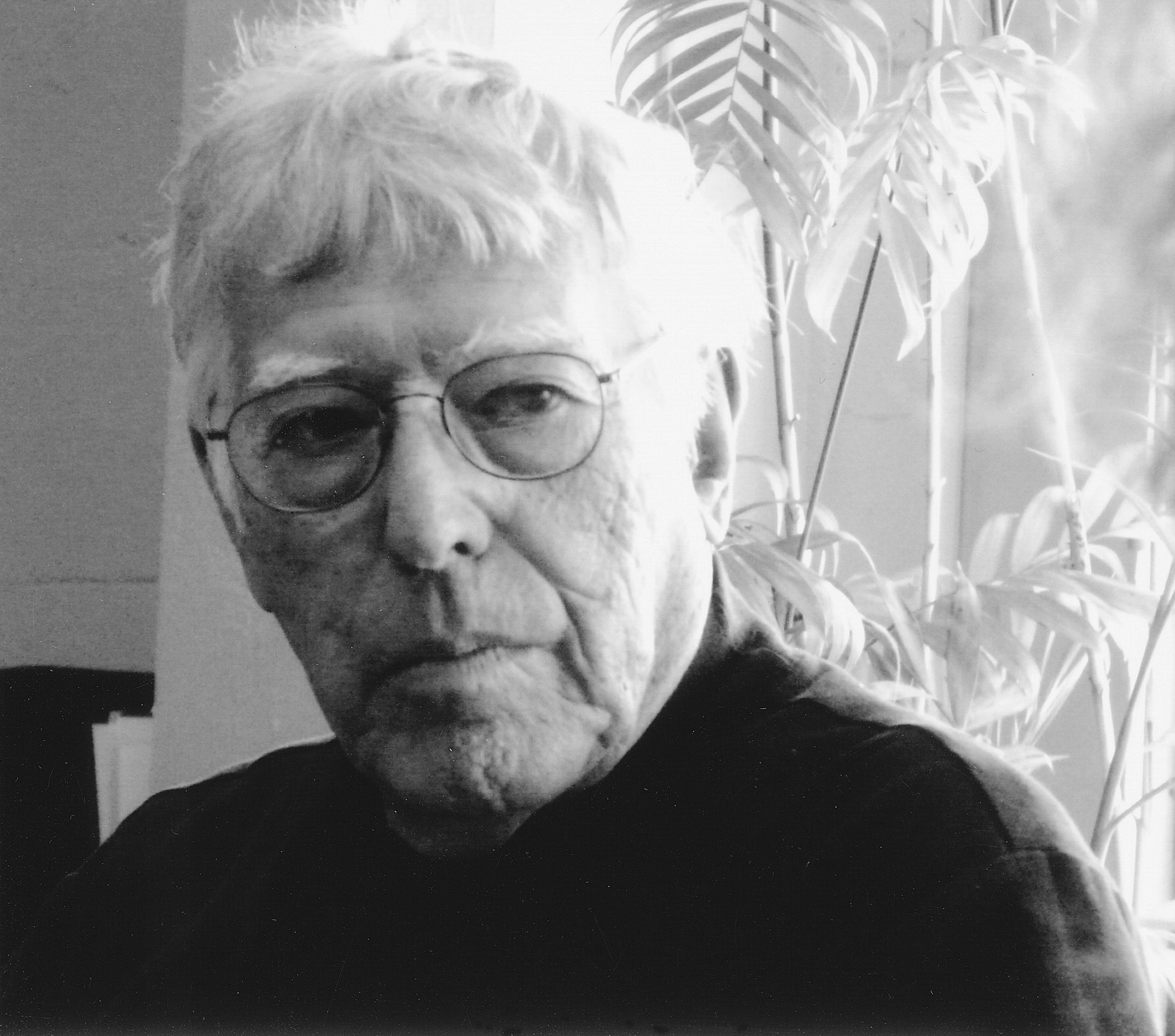

Photo by Christopher Felver.

— posted February 2014