Fruit Focaccia:

Breakfast with Susan

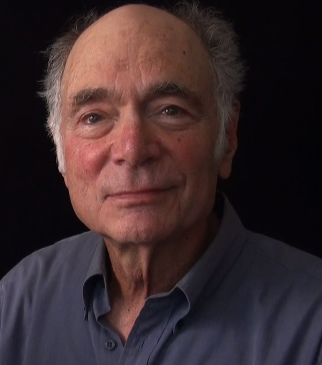

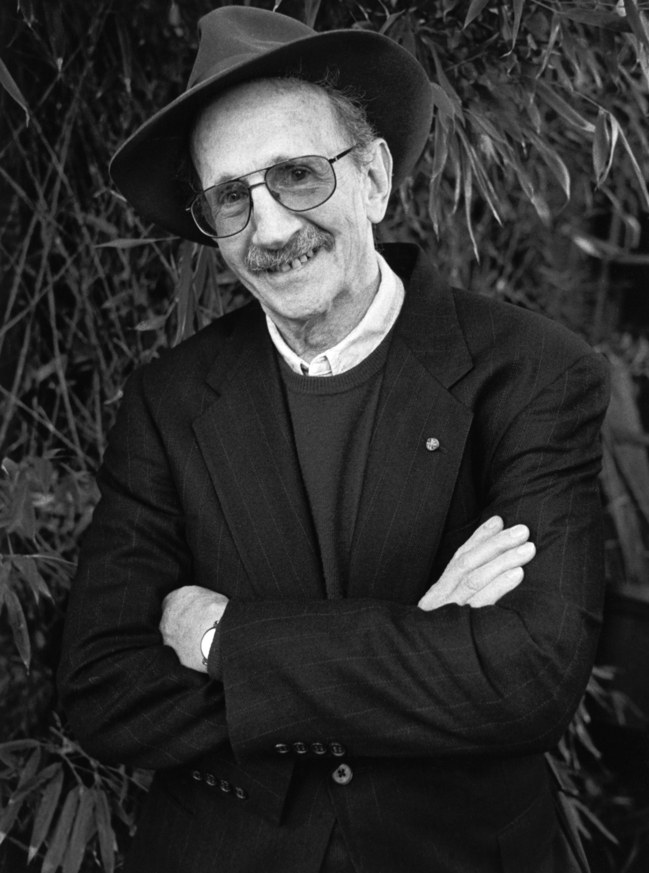

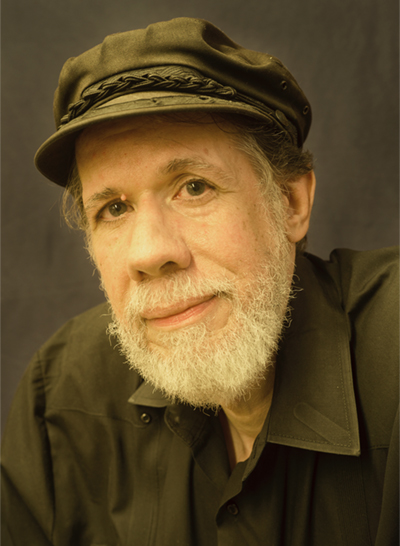

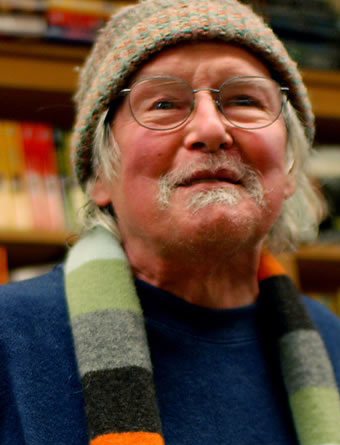

an homage by Carolyn Miller

Susan Herron Sibbet (1942-2013) was a poet, California Poets in the Schools poet-teacher, mentor, and irreplaceable board member, and longtime supporter of the Watershed Environmental Poetry Festival, where she presented CPITS student poets in remarkable onstage readings. Her books include Burnt Toast and Other Recipes, and most recently, No Easy Light. She was co-founder of Sixteen Rivers Press, a shared-work, nonprofit, publisher of poetry in the Greater (San Francisco) Bay Area.

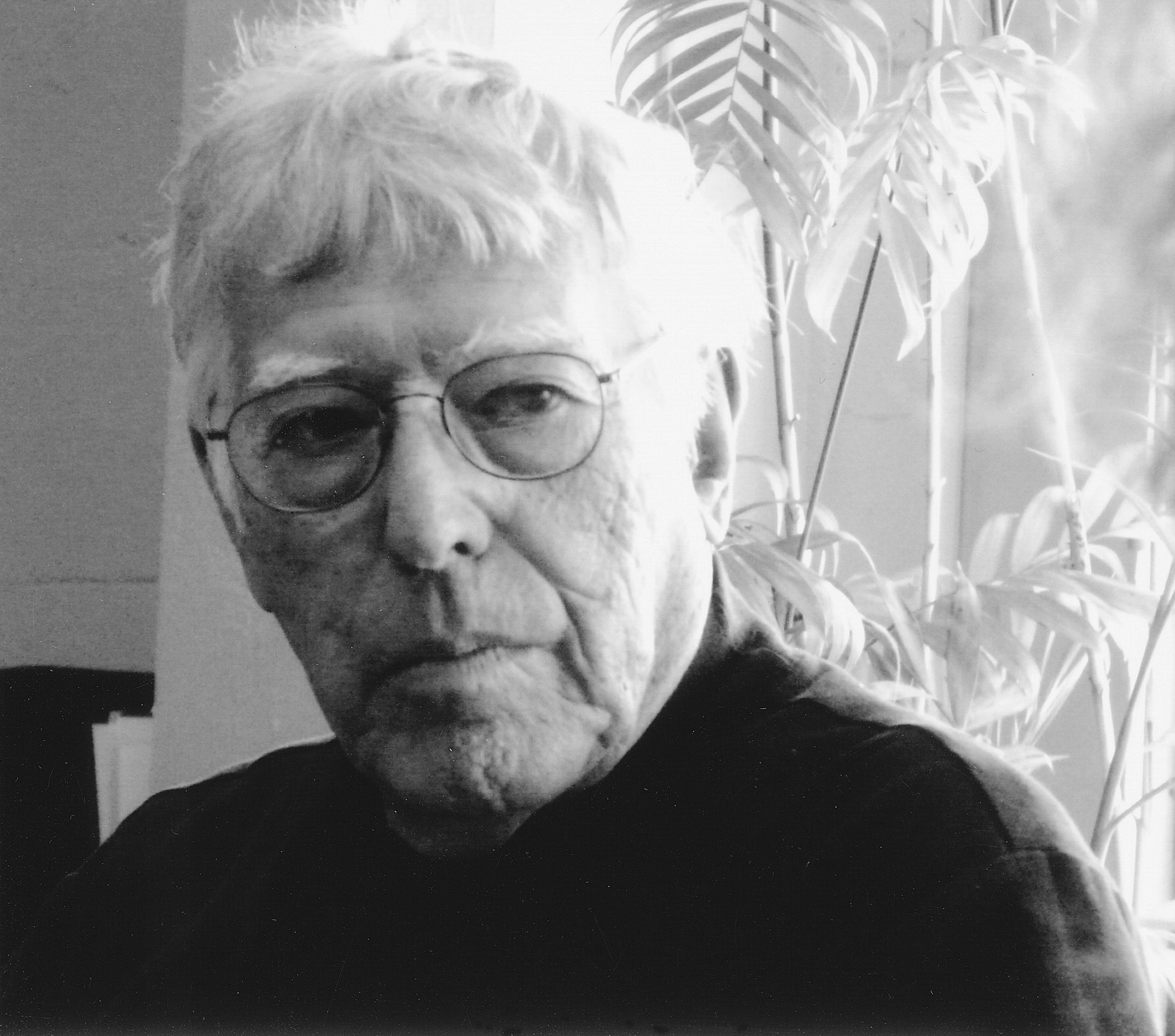

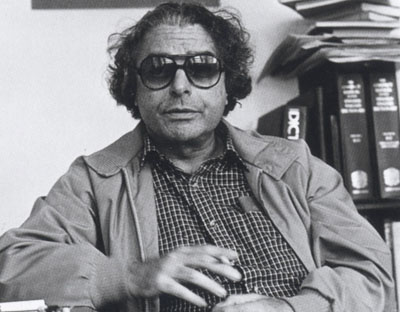

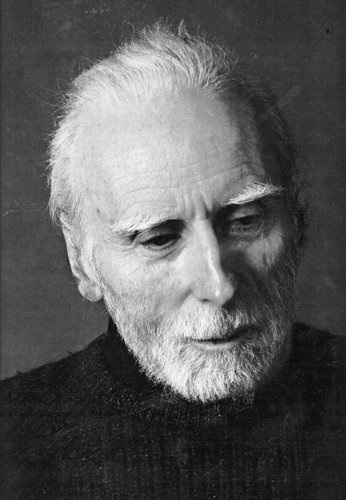

IT WAS IN THE EARLY EIGHTIES that Susan Herron Sibbet and I began to meet once a week for breakfast. We had met at the second annual Napa Valley Poetry Conference, while she was working toward her MFA at San Francisco State. She had wonderful thick silver hair, pale blue eyes behind silver-framed glasses, beautiful unlined skin, a brilliant smile, and an insistently cheery demeanor. Being a bit of a cynic, I was initially put off by her cheeriness, but I soon learned that she was a very human bundle of mixed emotions, and that cheeriness was her default mode. Shortly after that meeting, Susan joined the poetry group in San Francisco that Jeanne Lohmann and I had started the year before, after we two met at the first Napa conference; Terry Ehret, who was in graduate school with Susan, joined the group at the same time.

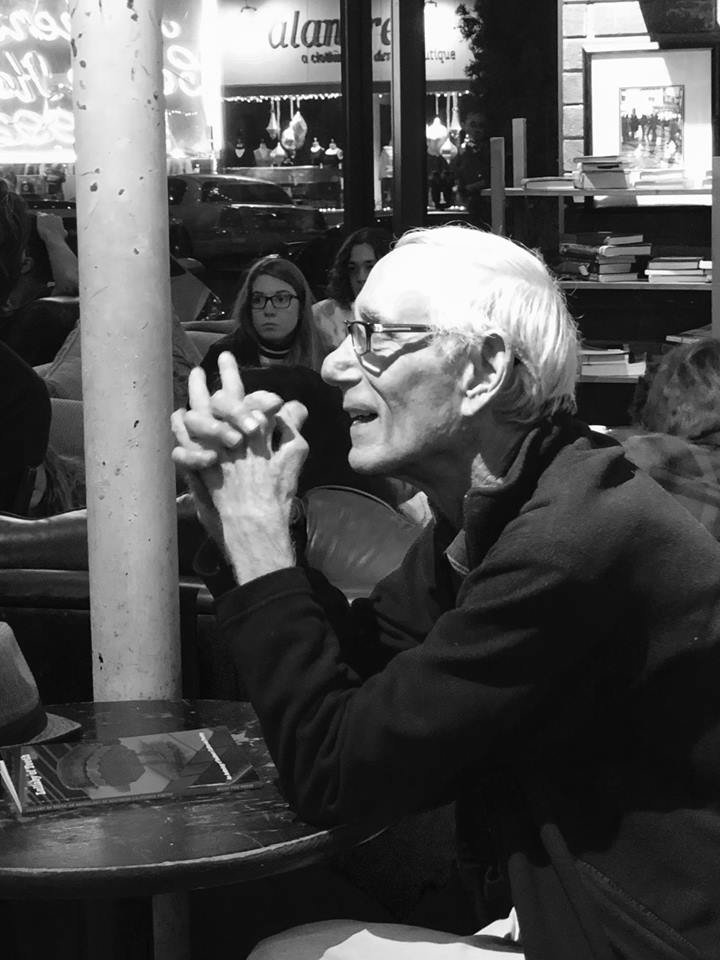

Susan and I decided to meet once a week to discuss our writing, with the idea of bringing in poems and working on them together. This soon changed to simply having breakfast and talking about our lives. The first place we met was Le Petit Café, a block from my house on Russian Hill. This little cafe was the home of excellent breakfast pastries and great oatmeal, served to us by Rosaria, who occasionally gave us free food. When Le Petit Café closed and became an Italian restaurant, Susan and I moved to the Grove, a larger café on Chestnut Street that, oddly enough, had the same name as Susan's husband's company, which was nearby in the Presidio. When that place changed owners, we decided we didn't like the pastries as much, and we moved to Rose's Café at Union and Steiner, where we continued to meet for the next twenty years or more, and which we liked because it was, and is, a true neighborhood place, open all day and serving guests of all ages, including children and babies.

Over the years, Susan always came to get me at my apartment on Green Street in a succession of cars that ended with Daisy, a Mini named for its colors, yellow and white, but also with a nod to Daisy Miller, the Henry James heroine, as Susan was a fan of James. She had done all her Ph.D. course work on him at Northwestern, and later started a novel about James and his secretary, Theodora Bosanquet, which she worked on at the Bunting Institute at Radcliffe in 1991.

Rose's Café is a focacceria, with a line of house-made Italian breads that accompany their breakfast, lunch, and dinner services. A highlight of their breakfasts is the fruit focaccia, which was made in thick slabs with the fruit folded into the dough, then baked and cut into squares. The first kind we tasted was strawberry focaccia, which seemed to us a brilliant marriage of the sweet and the not-sweet, slightly chewy dough and the luscious fruitiness of summer. We were dismayed when the baker stopped making them this way and started forming the dough in individual rounds, evidently in metal rings, which yielded too much crust around the edges in place of the former tender cut edges, and in our minds, ruined the entire concept of fruit focaccia.

Happily, after a long, bleak period, this version was replaced by focaccia baked in muffin cups with the dough blossoming up over the top of the cups, creating a heavenly, firm cloud of dough with layers of fruit that varied with the season.

All this time, Susan and I were talking to each other about what had happened the week before: our families and friends and colleagues, our writing and our socializing, our worries and our plans and goals. Susan loved to talk, and she spoke with great speed and energy, using hand gestures with abandon. She was passionately involved in the drama of her life and its large cast: a husband, four sisters, and three children, then a fourth child that she had given up for adoption and found again, and eventually seven grandchildren and a great-grandson.

As the middle child in a family of five daughters, Susan could never bear to be left out of things, so she was involved in many different groups. Consequently, she often over-scheduled herself and made herself frantic by trying to do too much. Her great love was community and communal activities, from food cooperatives to community gardens to Community Supported Agriculture, but most of all to California Poets in the Schools. She began teaching poetry in elementary schools in 1984, and held many posts with CPITS over the years, from president of the board to acting director. Every year, she spent considerable time and effort making books of poems for her classes, complete with art by the children, then holding poetry readings with them at the schools and later every year at the Watershed Environmental Poetry Festival in Berkeley.

Trying to help keep CPITS afloat consumed much of her time, energy, and emotion, as that organization went through all the trials and strains of a small nonprofit. She agonized over how to keep funds coming in and keep poets working in the schools. It's no exaggeration to say that Susan saved CPITS from extinction, probably more than once, with the sheer force of her efforts and her generosity. She did this because she believed young children in public schools deserved to be exposed to poetry, and she loved teaching poetry to them, and they loved her in return. She went back to the same schools year after year, invited by classroom teachers to bring poetry to their students. She amassed a huge number of lesson plans and books of her students' poetry over time. When I worked with her on some of the books, I learned that she seemed to know and relate to each individual student in her large elementary-level classes, and to appreciate and champion their work in a supportive and loving way.

Susan continued to meet with my poetry group from the time she joined, holding many of the meetings at her house on Sixteenth Avenue in San Francisco. We met every two weeks at one another's homes, but we especially loved meeting at Susan's, with her warm welcome, her wood fire, her garden, the fresh fruit from her CSA, and sometimes her homemade gingerbread or chocolate chip cookies or amazing brownies. We often left her house with bags of baked goods from Susan's oven or fresh fruit and strange and familiar vegetables from the CSA farm.

Over the years, people dropped out of the writing group, and new members joined, but Susan and I remained constants. Different configurations of the group not only met regularly for critique, but we also went on periodic writing retreats to places such as Inverness and Bodega Bay, where we wrote, read, walked, cooked, and ate. At one point, the critique group began holding all-day writing workshops four times a year on the solstices and equinoxes, and almost all of these were held at Susan's house, with additional poets from outside our group joining us. In 1999, we decided to form our own publishing collective with members from the solstice group, and the first meeting was at Susan's house, in the downstairs studio. We would go on to publish ourselves and bring in other poets from the Greater Bay Area in an open-submission process. That group, Sixteen Rivers Press, is still publishing poetry fourteen years later. Susan's own fine book, No Easy Light, was published in 2004.

And year after year, Susan and I continued to meet for breakfast, something that I looked forward to every week, often as a highlight of my week. It meant so much to me, as a person who lives alone and works at home, to have a friend whom I could meet with on a regular basis, someone I could tell everything to. And Susan was a devoted, loyal, and non-competitive friend who supported me in many ways, giving me work, lending me money, driving me places, buying my paintings, listening to me (especially when I would say, "Susan! Now, let's talk about me!"), and telling me that I was right no matter what personal conflict I told her about in excruciating detail. But the thing I liked most about Susan was her mind, for she was smart and opinionated, well versed in English literature, especially Henry James and his milieu, as well as politics and current events, and most of all she was funny in a surprising and imaginative way. I could always count on her to make a totally unexpected comment on almost any subject that would make me laugh, and making each other laugh was a large part of our friendship.

In becoming regulars at Rose's, we also became connoisseurs of fruit focaccia. Our favorites were the summer versions: strawberry, raspberry, blackberry. We were loyal to strawberry above all, for that had been our initiation into fruit focaccia, but raspberry and blackberry were close rivals in wonderfulness, and all of them were delivered to our table still warm from the oven with a faint dusting of powdered sugar and accompanied by the house-made strawberry jam. We were also appreciative of the huckleberry and the fig. Winter was a bit of a letdown, and we knew it had arrived when the strawberry jam was replaced by quince, and the summer fruits were replaced usually by apple or banana, our least favorite, even when pecans were added, though we were mollified on the few occasions when chocolate was part of the mix. The rare chocolate and pecan was a highlight of the season.

Because we always met on the same day of the week and at the same time, depending on Susan's teaching schedule, the staff at Rose's grew to know us and we them, though the waitstaff changed over time of course. But Jesse, the day manager, was there most every day of the week in the last few years, and as soon as one or both of us walked in the door (by then I had started walking to Rose's from my apartment, and Susan drove from hers), he would start making perfect double lattes served in big French cups that were delivered to our table without our asking, and the waitstaff would check with the kitchen to see how soon the focaccia would be done. Often after breakfast, we would walk past the Bud Stop, the sidewalk florist at the other end of the block, to look at the flowers just come in from the flower market, and sometimes we would buy one of their beautiful mixed bouquets for one another or ourselves. Just this year, we fell in love with the peonies, and bought several clusters of giant pink ones for our homes.

Susan and I did many things together over the years: we traveled together, went to movies and museums and poetry readings together, complained and gossiped and were negative and critical and judgmental together, worried and laughed and wept together, and most of all, we cheered each other on. We swam and went to the gym together briefly, and for several years, Susan drove us to Crissy Field before breakfast to walk for thirty minutes or so to justify having fruit focaccia later. Susan didn't really like walking (though she did like to swim, which she was especially good at), and when she was often breathless after walking we both agreed that she was just out of shape. At one point, I announced that I figured we both had twenty more years to live, and that therefore we should take care of ourselves, lose weight, and exercise more so those years would be healthy ones. Susan said, "Well, I don’t know if we can do all that, but I love it that you think we have twenty more years!"

But then she was diagnosed with uterine cancer, and though we thought that after surgery and radiation she was cured, we had to stop walking because her breathlessness became too severe, and eventually we learned that the cancer had metastasized to her lungs. She endured a course of chemo and lost her wonderful hair, but tumors next appeared in her brain, and a course of radiation did nothing to help. Now, our visits to Rose's became less regular, as Susan was no longer allowed to drive, and had to be driven to the cafe in Daisy by someone else. Still, we met. At first, she used a cane, then a walker to get to and from the car, and then we stopped going to Rose's altogether. I did bring pastries to her house for breakfast, but of course it was not the same.

When she was diagnosed with incurable brain cancer, Susan called me to tell me, and remarkably, she apologized for doing so, because she knew that I had lost several other dear friends in the past. But I am the one who is sorry for losing my brilliant friend, who loved poetry, children, words, domesticity, cats, fine literature and trashy novels, laughter, dancing, food, her friends and family, San Francisco, bright colors, movies, music, flowers, Henry James, Tasha Tudor, coffee, chocolate, English tea with milk, and so much else. I will be forever grateful for our long friendship, but I will never stop being sorry that someone who loved life as much as Susan did had to give hers up too soon. ![]()

Carolyn Miller is a poet, writer, book editor, and painter. Her most recent book of poetry is Light, Moving, her previous book is After Cocteau. She is also the author of two limited edition collections of poetry, and a number of cookbooks, including Savoring San Francisco. Her poetry has appeared widely in journals such as The Gettysburg Review, The Sewanee Review, The Southern Review, and The Georgia Review.

Photo by Maureen Hurley.

— posted February 2014