Find Your Passion

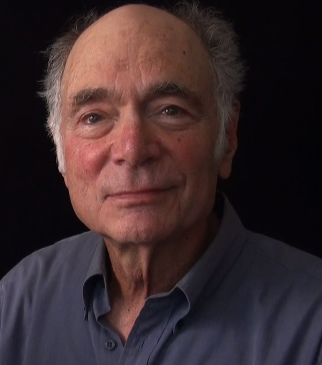

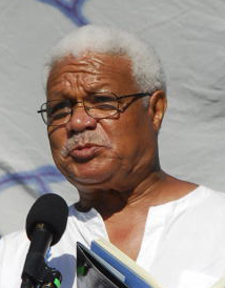

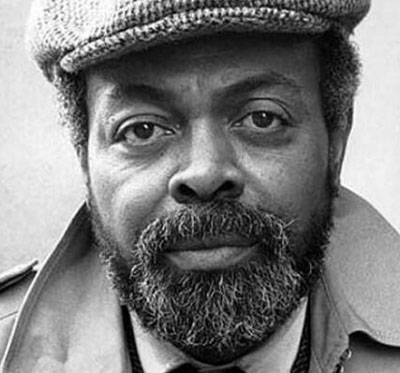

A Conversation with Lynne Thompson

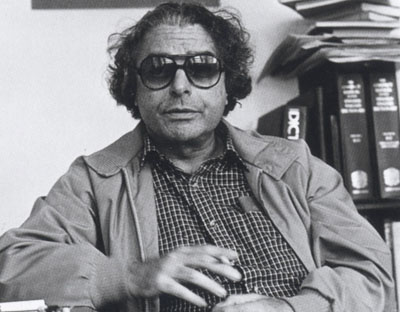

by Lee Rossi

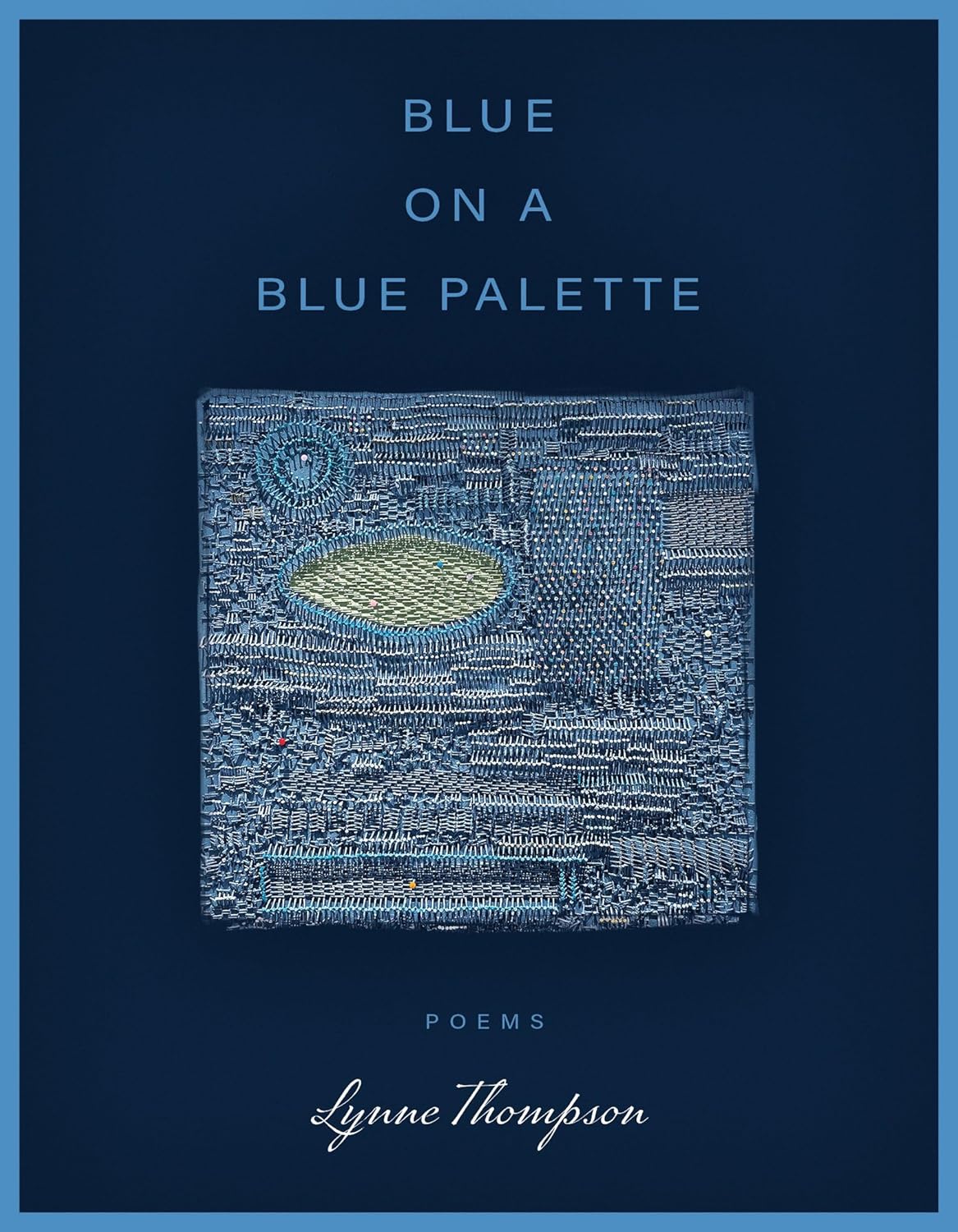

Lynne Thompson was Poet Laureate of the City of Los Angeles from 2021 to 2022. She is the author of four books of poetry, most recently Blue on a Blue Palette. She has been the winner of the Perugia Press Prize and the Marsh Hawk Poetry Press Prize (among others). Her poems have appeared widely, in publications such as Ploughshares, Poetry, Pleiades, and Best American Poetry. A lawyer by training, she sits on the boards of Cave Canem and Scripps College. In her spare time (!?) she leads poetry workshops at Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center, Moorpark College, and elsewhere. The following exchange took place during the summer of 2024, via email.

Poetry Flash: First off, Lynne, I want to say how much I enjoyed your new book, Blue on a Blue Palette. I feel like I learned something on every page—the rivers and peoples of Madagascar, a new kind of meditation and even the Swahili word for 'hello.'

You've said that you started as a storyteller, telling family stories in fairly straightforward, narrative verse. This is your fourth full-length collection and over the years your poetry has become trickier, more complicated, more formal, that is, more interested in how the poems say what they have to say.

So let's talk about the new book's formal restlessness. A very astute critic (myself) wrote the following about your previous book, Fretwork: "Thompson has a taste for forms with a repetition compulsion—villanelle, pantoum & sestina—reminding the reader that culture is a way of saying the same thing again and again, the point being for people to give up wanting what they want and instead take what society has to give, which for people of color is usually less and nothing." You write in a variety of forms, what appeals to you about form, what can you say in form that you can't in free verse?

Lynne Thompson: I'm not willing to go as far as to say one can say things in form that can't be said in free verse. For me personally, the appeal is in the challenge that formal poems set up. Whether writing a Petrarchan or Shakespearean sonnet, a ghazal or glosa or a terza rima, these forms have certain requirements that, when fulfilled, can produce something unforgettable. Because I like to make recommendations to readers, here are a few I love: Patricia Smith's "Hip-Hop Ghazal," (www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/49642/hip-hop-ghazal); Derek Walcott's "The Bounty," a terza rima (www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48318/the-bounty); and Louise Bogan's "Sonnet," (www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/148799/sonnet-5c1a797e31fb8).

PF: Although you do include more traditional forms in the new book—the sonnet, the pantoum, and the villanelle—I notice others, maybe more in favor with contemporary poets, the abecedarian and the cento. One thing about your handling of the abecedarian is the lightness and inventiveness of those poems. You seem to find a freedom in the form that I don't notice in other writers, e.g. myself. How long does it take you to construct one of these? Do you start with a particular theme in mind, or with a list of words in alphabetical order, OR do you just let it rip, knowing that the next line begins with the next letter of the alphabet?

Thompson: Sometimes I set out to write in form (I just completed a few drafts of a rather loose form suggested by Diane Seuss of "…fourteen-lines that reflect your current emotional state via an image" with no enjambment of the lines) but other times, especially with abecedarians, the possibilities of the form present themselves in early drafts. The time it takes to comply with a form's strictures varies wildly from poem to poem and the form it chooses to take but my general drafting process compares well to the tenacity of a dog with a bone! So when the muse sidles up to me, I work on the piece pretty constantly until it begins to look like what could be a final iteration.

PF: I also notice the many centos in the book. The word cento means "patchwork," and a cento is a poem composed of lines from other writers. What draws you to the cento? Why do you think you enjoy cutting and pasting the words of others into your own patterns?

LT: I'm a lifelong lover of puzzles and I place the cento in that category. The idea that I can take lines from poets I admire and reconfigure those lines so that they derive a new meaning, one not intended by their author(s) allows me to be in conversation with those authors which is thrilling on its own. It's also a great way of paying homage which I believe we, who stand on their shoulders, have an obligation to undertake.PF: Another thought I had was that a cento is a way of building a literary community as well as a way of establishing your own literary heritage. Your centos declare a lineage that includes Ai, Robert Hayden, Langston Hughes, as well as many others. I'm not the first to say this, but I think Eliot got it wrong: instead of titling that famous essay of his "Tradition and the Individual Talent," he should have called it "Talent and the Individual Tradition." How long did it take you to realize that the so-called Great Tradition was not the tradition that you wanted to build on?

Thompson: My problem with Eliot's "Great Tradition" was that it seemingly failed to recognize that it was neither the only tradition and it definitely wasn't the most inclusive. I was looking for other poetic traditions that spoke more closely to my lived experience—traditionally and experimentally—something I think I understood intuitively from the beginning. When I was twenty and heard Jayne Cortez for the first time, I said "ah…that punctuation thing doesn't have to be a thing.…"

PF: Another formal invention I very much admired and was amused by are your all-footnotes poems. I don't know if I've ever seen anyone do that before. I mean, contemporary poetry books are rife with footnotes, but then to write a poem that's only footnotes; I love the esprit, the insouciance. I'm thinking of "An untamed1 rebel resists2…," with it's almost flip dismissal of patriarchy, and "My1 Alchemists2 Dream3 in Cursive4," which asks the question, "if we are glad, is it because we know we are rich in everything we need to be rich in" but which also prompts the reader to answer with a ringing affirmation. In themselves, these are wonderful poems, but their typographic machinery adds so much, a sense of playfulness and rebellion.

So let me ask you, is this a satire on the contemporary MFA product, or something else?

Thompson: I wish I was a satirist! Maybe in the next solar return. No, the story of those foot-noted poems is a simple one. Years ago, in an installment of the Best American Poems series, I came across a poem (which I now can't find for the life of me) in which the title was followed by substantial white space and then text. I don't believe that text was in the form of footnotes but I wanted to capitalize on the visual metaphor of white space so I decided on the footnote format. The key is to find a good title deserving of being footnoted!

PF: One form I did not see a great deal of is the ode. Public poets, laureates, typically produce nothing but odes. And we can name any number of contemporary poets whose stock in trade is 'the praise poem.' You do, however, offer one such poem in your book, the very last poem, which given its position emphasizes its uniqueness. Let me read the first few lines:

Say hallelujah

because it strikes me: I ain't writ no praise-songs yet. I got

laurels and a two-step platform but damn if I deserve them

when I ain't writ no praise-songs after living long as this.

Okay, so here we have a dialect poem masquerading as an ode. It's naughty, haughty, and full of life's disappointments. Who or what is the butt of your joke? Anyone we know? And more to the point, why don't you write more odes?

Thompson: I didn't see the topics that Blue on a Blue Palette reflects upon as being ode-worthy. The collection addresses murders, tortured histories, and a loss or questioning of faith, among other issues. Nevertheless, it was important that the collection close with a recognition of the praise which anyone, having survived this life for any length of time, is entitled to…I guess I'm the butt of the joke!

PF: Of course, you're not in this racket simply to entertain. You'd be writing sitcoms or genre fiction if that were the case. What's really on your mind? What do you want your readers to take away from your poems? You did an essay, which appeared back in April, in which you described the process of putting this book together. You emphasized, for instance, that these poems were written during the past ten years, ten difficult years. You also wrote that many of these poems focus on your long-standing interest in the plight and concerns of women, especially women of color.

Can you elaborate on what you found most alarming about the last ten years?

Thompson: I don't think Poetry Flash has enough print space for me to discuss what's been most alarming in the past ten years. But as I'm answering this, VP Kamala Harris has just been endorsed by President Biden and other Democratic leaders as Biden exits the campaign. So I'm feeling hopeful this evening. However, on the ground, women are still being trafficked, killed, underpaid, and I could go on and on. Blue… can't solve any of these issues but the hope was to [briefly] highlight some of the struggles that women continue to endure and have endured for centuries.

PF: How has the situation of women improved or degraded during that time?

Thompson: Women have struggled to break the glass ceiling professionally; to have their voices heard politically; and to make their presence visible as younger, older, body-shamed, financially viable persons. When I think of my great aunt (Ida Perry to whom I dedicated the poem "A Confluence of Women") fighting with the International Women's League for Peace & Freedom in the 1920s, I can't believe we're still fighting some of those same fights. On the other hand, we are on the precipice of electing a woman for President of the United States and, if we can pull that off, it will be a remarkable achievement.

PF: How has the situation of people of color improved or degraded during that time?

Thompson: Of course, there have been improvements in the lives of people of color in America in the twenty-first century. Nevertheless, as I answer this, I'm following the circumstances surrounding Marcellus Williams, an African American man, who is scheduled to be executed in September despite the DA on his case saying there is clear and convincing evidence that Williams did not commit the crime of which he's been convicted. As I write this, the public is learning the details of Sonya Massey's murder by a police officer who shot the African American woman in the face after she called 911 for help. The fact that these circumstances continue to persist is terrifying and undermines any so-called improvements in conditions for African Americans, in particular.

PF: Maybe we can talk how some these themes shake out in individual poems.

"Blue Night with Scissors," (the first poem in the book), for instance, starts with a sense of threat and despair, situating the speaker as a devotee of the moon and the laurel (a poet) while those surreal scissors "twirl light in the lattices." I think the poem invites us to understand the scissors as both negative and positive, as emblems of separation but also as tools of a certain kind of artist (the late Matisse, for example, or the cut-up sonneteer Ted Berrigan).

Why did you choose that particular poem to begin the collection?

Thompson: Your question touches on the topic that terrifies me—and others, I assume—as a poet: how to open a collection of poems. And as you can imagine, I went through several re-orderings. I ultimately settled upon "Blue Night with Scissors" as a mood setting piece, one that spoke to struggle on the one hand, and to restoration, on the other, all in a surreal environment.

PF: This book is so strong from the very beginning. The next poem, "A Confluence of Women," is an abecedarian, Ashbery-like in its use of zeugma. You write that women have "always the sense we've assembled ourselves as / barmaids or burdens of proof, / courtesans or / drama." And yet the poem is a defiant declaration of solidarity with the oppressed, projecting a tone of optimistic desperation: "we are, quick to / whistle while drowning but not to worry." Is that how you see the situation of women in American society, desperate yet hopeful?

Thompson: You've captured the poem's intent perfectly. As we enter the political season of the Harris campaign, women are aware of how negatively we are often viewed in the public arena but nevertheless refused to accept those viewpoints that are negative or disparaging.

PF: Poets (some poets, anyway) do a lot of reading, but you seem to do more than most. Many of your poems are in conversation with other writers; in the first few poems I notice Lorca, Terrance Hayes, Sonia Sanchez, Mary Ruefle, and that's just the first few pages. Here are a few lines from your poem "Variations on Lines by Linda Gregerson":

…To be like

a woman is to be

becoming, ever spun

around, the motto on

an unguided path, open-

throated. Release. & a fever.

What the reader experiences in passages like this, I suspect, is the consolation to be found in conversation with other like-minded spirits. Is that how you think about your alluding and colluding?

Thompson: Yes, the opportunity to be in conversation—or in collusion, which I love—with writers that I admire is an inspiration for me, as a writer, and offers a new occasion to reflect upon the work of these writers.

PF: Another important theme in the book—or at least one I noticed because it's one of my own chronic concerns—is an awareness of personal limits. For example, in "Inner Assassin" the speaker acknowledges the "existential jambalaya" which dwells inside her, "a virtuous mob¬¬ / of mother wit & mother woe." Is that you on a bad day, or just any day?

Thompson: I'm laughing as I answer this because it's definitely me on a bad day or even on a day that's not so bad but still challenging. I also found a way to make sure I have the last laugh where personal limits are concerned; thus, I wrote the poem "A Woman's Body, Aging, Still Loves Itself"—"the belly, brown, round, kisses its inverted button"— in an effort to stave off and stare down the inevitable.

PF: Yet through it all, you manage to be funny or at least amusing. I adored "Mosquitoes Consider Tourists Who Come to Tahiti." I can't remember if I've ever read a dramatic monologue spoken by a mosquito. I love the bloodthirsty enthusiasm with which the mosquitoes (she calls her troop "whiners") consider their prey: "All [these women] hear in the moonless night is the sound of our / excitement as we prepare to drink their blood…to savor their metallic bitterness crusting our tiny spears." All I can say is, Yum, yum. How do you maintain your sense of humor?

Thompson: I try to remember that I'm less than a grain a sand in the big scheme of things and looking at the world with that perspective in mind, I just have to laugh. Also, when humans can reflect on how the non-human world interacts with us, there's great humor—and humility—to be found in imagining the non-humans' view.

PF: If you have time, maybe we could talk a little more generally about the state of the art and the role as poet laureate in the life of the literary and wider community.

Being poet laureate is a many faceted role—as an advocate for the art of poetry, (and quite probably for all the arts), you're an educator, an entertainer, and who knows what else? In your experience what was the most challenging aspect of laureateship?

Thompson: I can say that my appointment as Poet Laureate—as well as the appointment of others to that role at about the same time—was made all the more challenging due to the pandemic. The role calls for substantial interaction with the community and all Poet Laureates had to rethink the ways in which we could fulfill our obligations given our isolation. Thank goodness for Zoom and similar platforms that afforded me the opportunity to communicate with libraries and schools and other organizations. And thankfully, in the second year of my appointment, I organized a reading and photo shoot for about 125 poets in the LA area at the Central Public Library. It was truly the highlight of my tenure.

PF: I'll bet you didn't read "Call It Havoc" to the LA City Council, where we read: "we live in cities of the already-dead, / justice just a fairy tale." Or am I wrong. I noticed—with a smile—that this is another abecedarian poem.

Thompson: I didn't read it to the City Council but only because I wasn't invited to read for the City Council (which was also in lockdown). I would have wanted to, however, because it's important for our politicians to be aware of the issues that trouble the sleep of those they represent. I would have given anything to have "incite[d] the passions instead of the faculties of reason" as Plato said in The Republic.

PF: Oh by the way, in England the Poets Laureate receive a barrel of brandy. Did you get a barrel of brandy, or maybe a kilo of sinsemilla, something to take the edge off the various demands of the job?

Thompson: No barrel of brandy, no kilo of sinsemilla or soporific of any kind! I did, however, make new friends, interact with organizations that I didn't interact with prior to my appointment so those things were their own reward.

PF: LA is a world cultural center, it generates immense revenues for record companies, for film and television producers; why do you think the City Fathers (and Mothers) even bother with poetry, and other so-called minor arts (dance, painting, sculpture, etc.)?

Thompson: Perhaps because as Pablo Picasso said, "Art washes from the soul the dust of everyday life." Further, there are numerous examples of film and television producers that often look to poetry (think Four Weddings and A Funeral when the actor recites Auden's lines "Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone, / Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone"). So the poets have their say in multiple, subtle ways.

PF: You've been poeting a long time now; how has the LA poetry scene changed during that time? Have you seen similar changes nationally?

Thompson: I think the poetry circle is wider and the poets are more willing to interact with each other across racial, geographic, and other cultural lines demarcating identity. I attribute this positive change to the efforts of literary centers like The World Stage and Beyond Baroque, among others; to literary organizations like Get Lit and Write Girl, among others; as well as to grassroots organizations and venues like Women Who Submit, 826LA, and LA Poet Society. Also, one can't ignore the proliferation of writing programs in the academy: UCLA, USC, Loyola Marymount, and others. And having served as the recent Chair of the panel that bestowed the Kate & Kingsley Tufts Awards, I want to give a shoutout to those programs that recognize and honor both established and new writers. I know I'm missing many others but you get the idea.

PF: Sometime back in the nineteenth century, Shelley infamously quipped that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world," which suggests that the status of the poet has been in decline ever since. What do you think is the responsibility of the poet to their society.

Thompson: On social media recently, I quoted the NBA award-winning poet Nikky Finney who said "[m]y responsibility as a poet, as an artist, is to not look away." I think she says it better than I could, and I try to bring that obligation to take responsibility into every poem I write.

PF: I'm sure you remember when we used to get lengthy articles about Iron Curtain authors and their struggles with censorship and oppression, an interest which seems to have disappeared now that Russia and her former satellites are safely capitalist. Do we need a ruthless autocracy in this country (ala the Soviet Union) to remind us of the importance of poets and poetry?

Thompson: I can't find any basis to establish a "ruthless autocracy" —something we're dangerously close to allowing—in the U.S. Poets can take care of themselves and will always find ways to assert the importance of the genre, of their work.

PF: William Carlos Williams once wrote: "It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there." What do you think he was talking about? If it's not the news, what do we find in poetry that is vital and necessary for human life?

Thompson: Poetry accomplishes different things for different people in different times, and the poet doesn't necessarily determine what those things or times are. One of the things that I've learned in discussions about not only my poems but the poems of others is that where I may interpret a poem as describing a beautiful garden, another person may interpret that same poem as describing the impact of climate change. I guess I'm saying that we find in poetry a way to be empathetic toward each other individually as well as to the rest of the world—man, beast, and nature.

PF: Tongo Eisen-Martin, a recent Poet Laureate of San Francisco, writes blood-thirsty poetry, but he also teaches, attempting to disrupt the ideological apparatus of late capitalism. He's written a curriculum about the extra-judicial murder of black people called "We Charge Genocide Again." Did you see part of your role as 'stirring up s***?

Thompson: Absolutely. One example in my recent collection is the poem "Among Peaches" which challenges the conception that women of a certain age no longer have a libido. I wanted to contest that idea in the strongest, and simultaneously, the most humorous, terms possible.

PF: How did your term as Poet Laureate impact your own writing, your own poetry? Was it positive? Negative?

Thompson: I was so consumed with the obligation to represent and connect with the residents of Los Angeles that my writing suffered to some degree. What I was able to do was re-read and compile poems I had written in previous years and ultimately develop them into the collection Blue on a Blue Palette.

PF: Was there anything you wanted to do in your term as laureate that you didn't get around to?

Thompson: One of the goals set out in my contract with the City was to organize a literary festival. As I stated above, due to the pandemic and the length of time it took to develop and administer an effective vaccine, I was unable to do so. I hope that my successor will be chosen soon and that person will be able to organize such a festival, as I think it would be uplifting for the literary community and beyond.

PF: What is your overall assessment of your term? Would you encourage other poets to take on those responsibilities?

Thompson: I'll leave it to others to assess my term, but I'd definitely encourage other poets to accept this responsibility if offered. I've long held the belief that in addition to developing one's own craft, it is important to be a good literary citizen, to help others in big and small ways as they work to develop their craft. It not only makes one feel good to be a supporter and mentor to others, it creates a deep sense of being part of the community on the part of the person helped. I have had way too many supporters to name here but each and every one of them contributed to my development as a poet and poetry citizen and I will always be indebted and grateful to them.

PF: What's next for you: another book of poems, a memoir, a book of essays?

Thompson: I have some ideas rolling around in my head for a new book of poems. I've been encouraged by others to consider a memoir that addresses, among other things, my journey from lawyer to Poet Laureate, as well as my vision of family given the interesting stories of both my adoptive and birth families.

PF: What haven't I asked that you would like to talk about, something that the readers of Poetry Flash need to know about Lynne Thompson or poetry?

Thompson: I'd only conclude by saying find your passion; it will nourish you in innumerable ways.

PF: Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts with me and the readers at Poetry Flash . We all benefit from your work so much, its skill, its ambition, and its humanity. ![]()

Lee Rossi's new poetry collection is Say Anything. His previous collections include Darwin's Garden: Studies from Life, Wheelchair Samurai, and Ghost Diary. A contributing editor for Poetry Flash, he is a member of the Northern California Book Reviewers, who juror books for the Northern California Book Awards; his poetry, reviews, and interviews have also appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, Poetry East, Chelsea, and elsewhere. He lives in San Carlos, California.

— posted April 2025